NEWS

NEWS

Seoul by night, 2014, © Woogeon Choi.

Close Encounters of the Seoul Kind: Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (SIBAU)

A major international symposium staged in October 2016 to discuss the new SIBAU – Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism – anticipated a paradigm shift in Seoul’s architecture culture and co-created regenerative urban design processes

Changgyeonggung Palace, Seoul, 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

How can a city be experimental with itself? In Victorian times in the UK philanthropists applied notable social experiments in urban centres to extend welfare, enlightened and largely top-down. Throughout the 20th century there was a consistent thread of utopian activity by architects and reformers forging prototypical housing, transport systems, amenities and neighbourhoods, along with their paper trail of drawing board urban utopias.

But today the unprecedented scale and the evolving conditions of urbanisation are encouraging groups and organisations in cities from every continent to try out new ideas functioning as mirrors of possibilities and solve pressing problems – some stemming from urban growth or shrinking; others from climate change; still more from loss of cultural identity, and a few slowly introducing new legislation to enable facilities and greater security for larger sections of the community.

Han River, Seoul.

The megacity of Seoul, South Korea, has been undergoing an intense process of transformation and expansion, with over 10 million inhabitants and a population of nearly 26 million in its greater metropolitan areas. Rather than continue to form and implement urban policy without cultural discourse and enquiry through events, it is highly appropriate that it has created such a vehicle of urban experimentation in the form of the Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism as a unique type of new and open institution designed to help develop the city’s architectural culture. Could it go so far as to effect a paradigm shift in quality of operating systems embracing the wider public?

Old and new Seoul, 2007, © YoungDoo Carey.

Traditionally the biennale as a cultural event has been one about art, based on exhibited objects, and drawing most notably on its most prestigious early adopter in Venice. Although expanding rapidly as an urban phenomenon, the biennale is a vehicle many cities still do not have, although they may have an architecture week or festival of a smaller kind promoting community networking on the ground. The cultural function of exhibiting new work and generating debate in the field of urban design and planning has fallen to architectural centres, some with interactive models of their urban landscapes, eventually updated when enough changes take place.

Street party, Jongno jewellery district, Seoul, 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

But it is still hard to convey the notion of architecture less as a spectacular set of static objects, and more as soft planning ideas and processes the city can benefit from through formal means. One of the biggest challenges a city has is overcoming the natural tension between the spectacle of a Biennale and the imperatives of longer-term regeneration, to achieve high level results that satisfy both objectives. With the Seoul Metropolitan Government as instigator and mediator of the Biennale, rather than a more privatized set up, Seoul surely has a high chance of doing that. After its period of rapid growth Seoul needs to reflect on how to redefine its identity, as many local and international commentators have observed. It is clear that social interaction and experimentation through live debates, workshops and networking activities to build a sense of wider ownership of ideas has to be a central principle. Both the software (ecological cycles, public involvement, cultural vehicles) and hardware (infrastructure projects) of cities, and perceptions of value, have to feature in this discussion. Inevitably, full-scale evolutionary change is a very slow process, and increasingly local populations must have a genuine say in proposals. Seoul’s recent era has shown many signs of taking progressive steps for urban improvement. So for taking the courage to stake out the future through experimentation and prototyping new processes, its urban municipality is to be congratulated. A little can go a long way, but society today wants more openness and valuable momentum today can only be built through popular new urban mechanisms.

Gangnam intersection, Seoul, © Brad Hammonds.

In the case of SIBAU, its first edition is projected for 2017, so for this major new institution, unprecedented in the city, it is vital to have extensive debate to test out ideas and get feedback, and allow polemics to be expressed, to help advance the template of this major cultural event be held. Accordingly, SIBAU staged an impressive two-day long local symposium in October 2016 with invited international speakers. It was the right thing to do to mark the genesis of the Biennale, rather than conduct discussions wholly behind closed doors. The event fully underlined the unique history, economy, culture and politics that makes Seoul a fascinating location and incubator for such a big civic commitment. A subsequently released publication, Seoul, an Urban Experiment: Starting the Seoul International Biennale on Architecture and Urbanism (Seoul Metropolitan Government, December 2015) also ensured that it was a crucible of reflections and propositions of ways to go forward.

Alejandro Zaera-Polo (AZPML, Princeton University, Director, SIBAU symposium), © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

‘As a thriving Asian metropolis that has now become one of the main urban centers in Northeast Asia, in many ways, Seoul represents the concerns and opportunities of the region of the world where urban development is most intense’, says Alejandro Zaera-Polo, the Princeton University-based architect and urban designer (AZPML), Director of the SIBAU Symposium, praising Seoul’s ‘rich tradition as a designed city: from its own foundation in the 14th century by King Sejong to the Gangnam Style phenomenon’, with ‘one of the most original urban cultures in the world that is unfolding in a multiplicity of forms’.

H-Sang Seung (City Architect of Seoul), SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

City Architect, H-Sang Seung, advises the Seoul Metropolitan Government on issues of quality and built environment. Seoul is a megacity with 1000 years of history and beautiful natural resources, which was made the capital of South Korea 600 years ago. It has been invaded, occupied and destroyed and burned to the ground during the period of Japanese imperial occupation (1910-1945) and the Second World War. From being the capital city of the world’s poorest country, Seoul grew tremendously under government economic development policies, and took on a ‘mask of modernity’. While acknowledging this compromise, Seung feels that Seoul is fiercely transforming to recover its identity’…for ‘nature and history cannot disappear’.

Unfortunately neither nature nor history can be taken for granted: they require resilient design and planning visions or they can become degraded or eliminated. So how can a Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism best operate to benefit the city? The most interesting and effective Biennales to date – and the Venice Biennale of Architecture is the most notable and longstanding of the lot – have been those that offer a genuine mirror to citizen’s identities, desires and interests.

Alejandro Zaera-Polo, Director, SIBAU symposium and moderator Hyung Min Pai (University of Seoul), SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

Unfortunately while there may be a lot of content in biennales dedicated to worthy social causes globally, as in the case of the Venice Architecture Biennale or the Shenzhen Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, very often there is too much a chasm between the Biennale and the communities and neighbourhoods of the host cities, and the issues they are facing. Mere token events are often the rule, which do not fully engage with locals, giving rise to the perpetuation of cultural insularity. Then there is the challenge of showing processes rather than objects alone. While the SIBAU symposium debates over the two days revealed the fault lines between architects, planners and policymakers, Zaera-Polo is keen to identify new forms of architecture related to the processes of creating wealth and happiness (a concept high in priority in the Seoul Urban Plan of 2030).

City walls at Ihwa Village, Seoul, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

Accordingly he and Seung regard it of vital importance that the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism be research-driven, informed by real time events and patterns on the ground, rather than by instant trends, in line with the longer term nature of public infrastructure development; its events on each occasion have to be driven by a theme, one that takes a global perspective on urban challenges, including neglected spaces and sectors of the population. Reflecting the fact that more than 50% of the world’s population live in cities, the Biennale will centre on the challenges of cities, rather than countries, making a global call for participation. It has to embrace the multidisciplinary nature of urbanism in Seoul and globally and make multiple concerns its focus, embracing a wide cross-section of audiences. Zaera-Polo envisages SIBAU as ‘a think-tank for Seoul in which local processes will be regularly exposed to the scrutiny of global experts visiting the city every other year.’ He recommends that SIBAU avoid becoming like MIPIM, the largest developers’ trade fair held annually in Cannes, an elite market place full of the sound of soundbites by mayors selling their latest commercial urban schemes. SIBAU should ‘not be selling real estate but knowledge.’

Seoul from Namsan Tower, 2012, © Marcelo Druck.

This is essential, because there is no shortage of globally relevant and pressing urban issues shared by Seoul with the rest of the world’s cities: urban recycling and waste treatment, air pollution and carbon emissions, transport infrastructure, ageing population, how to create more provision for housing for younger generations and others on lower incomes, quality of green space and urban agriculture, how to build resilience and more. Knowledge economies can break issues out of their siloed boxes beyond their ‘sell by date’ and bring new, lateral solutions.

Secret Garden of Changdeokgung Palace, Seoul, 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

Rapid urban development creates economic, cultural and social conflicts and paradoxes: a complex cocktail of issues. One of the key questions at the Symposium was whether the new SIBAU could become a local policy device as well as a field of urban experimentation, without compromise? On a more macro level, to what extent does the global milieu affect the planning of a contemporary metropolis, and how far are local issues sufficiently addressed? In what ways can Seoul develop in order to be seen as a model for sustainable development? Clearly the answer to that question is by some means of experimental urbanism, prototyping new processes, as the Japanese become famous for doing before the bubble burst in the field of product design, and, across the world, examples of such tactics in the field of adaptive urban design and planning, are growing, and being tracked.

1825 map of Seoul painted on tiles lining the Cheonggyecheon Stream running through the city, © Jerry Michalski, 2007.

Seung, in his opening talk, referenced the mixed living structures of Seoul 9000 years ago, as well as the balance of rich and poor in Pompeii 700 years ago. What modern cities are now trying to achieve, he reminded us, has been done before. The original Roman military camp was the birthplace of modern Western cities, with its diagram based on flat land, perfectly geometric, nothing to do with local topography, superimposed on places. He evoked Henri Lefebvre’s comments about the Cartesian use of land, compartmentalizing it, and turning people away from each other. Seoul, in the 19th century a warzone of class and strife, ‘destroyed and rebuilt like a mirage’, also suffered flattening diagrams, but newer ones finally accommodated its topography. A city, as Italo Calvino said, holds many traces of the past; it is a living thing with memories and desires.

Rather than be dominated by landmarks, Seoul should have a multiplicity of centres, Seung continued, and be a network city with shared experiences – with co-housing, for example, and greater exposure to the ru (ral)-urban. He wanted the focus placed on regeneration rather than redevelopment; network rather than landmark; urban acupuncture rather than masterplanning; becoming rather than being. The aim, too, was to ‘diffuse borders between the Biennale and the outside (the city)’, said Zaera-Polo. ‘The Biennale needs to be situated (there)’, describing Seoul as ‘large, dense and thriving, with a very strong planning department’. It could build on these capacities, perhaps in a way similar to that of IBA Berlin or the municipality of Barcelona, through ‘a new system to be a point of governance, and by ‘becoming a think tank for cities’. By integrating city planning and a new vehicle like SIBAU, the Biennale becomes instrumentalised to enable the evolution of urban knowledge.

The Seoul Experiment session discussion with Alejandro Zaera-Polo (Director, SIBAU symposium), moderator Sarah Ichioka (New Intentional Communities Project), Myung Rae Cho (Dankook University), Miree Byun (The Seoul Institute) and Chang Heum Byeon (SH Corporation), October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

Seoul’s rapid urbanization from the 1960s-80s saw land readjustment through new economic mechanisms, explained Mack Joong Choi, Dean of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies of Seoul National University. During the 1990s, many people moved out to the Metropolitan Area where now more than half of South Korea’s population now lives. The predominant housing type was high density, relatively compact apartment blocks.

Gangnam, Seoul, 2012, © Daniel Heo.

While areas like Gangnam evolved with linear office strip development housing global corporate headquarters, Seoul was suburbanizing, with New Towns like Bundang (1989) and Pangyi (2003) created from the 1990s-2000s. Today, ’10-15 million people come into Seoul every day…Seoul has sprawled, but in a densified pattern’. The criticism is that it is ‘just a bed town’, lacking a city-regulating strategic plan. By 2010 Seoul was stabilizing, or even shrinking with the lowest birth rate and an aged society, giving less incentive for people to move from outside into the city.

Cheonggyecheon stream, Seoul, 2008, © Kimmo Räisänen.

Because urban development backed by excessive demand was no longer valid, this triggered a search for a new paradigm. Public agencies were relocated to ten different regions to achieve a better balance. Five phenomena shifted the ground in a major way: the restoration in 2005 of the internationally acclaimed 11km Cheonggyecheon Stream, a neglected waterway hidden by an overpass, which some people criticize as ‘too artificial’; the historic preservation of the CBD, and the creation of mass transit with modal transfer using IT technology, as part of the 2030 Seoul Plan with goals and implementation strategies, introduced by the Seoul Metropolitan Government, which heralds it as a plan decided by citizens at every stage, by contrast with all previous plans for the city; and ‘Han Ryu’ (Korean wave), the global influence of South Korean culture manifested by K-pop and its megastars including G-Dragon, since the late 1990s, and subsequent fostering by government of the cultural industries, keen also to see an appreciation of multicultural experiences locally as well.

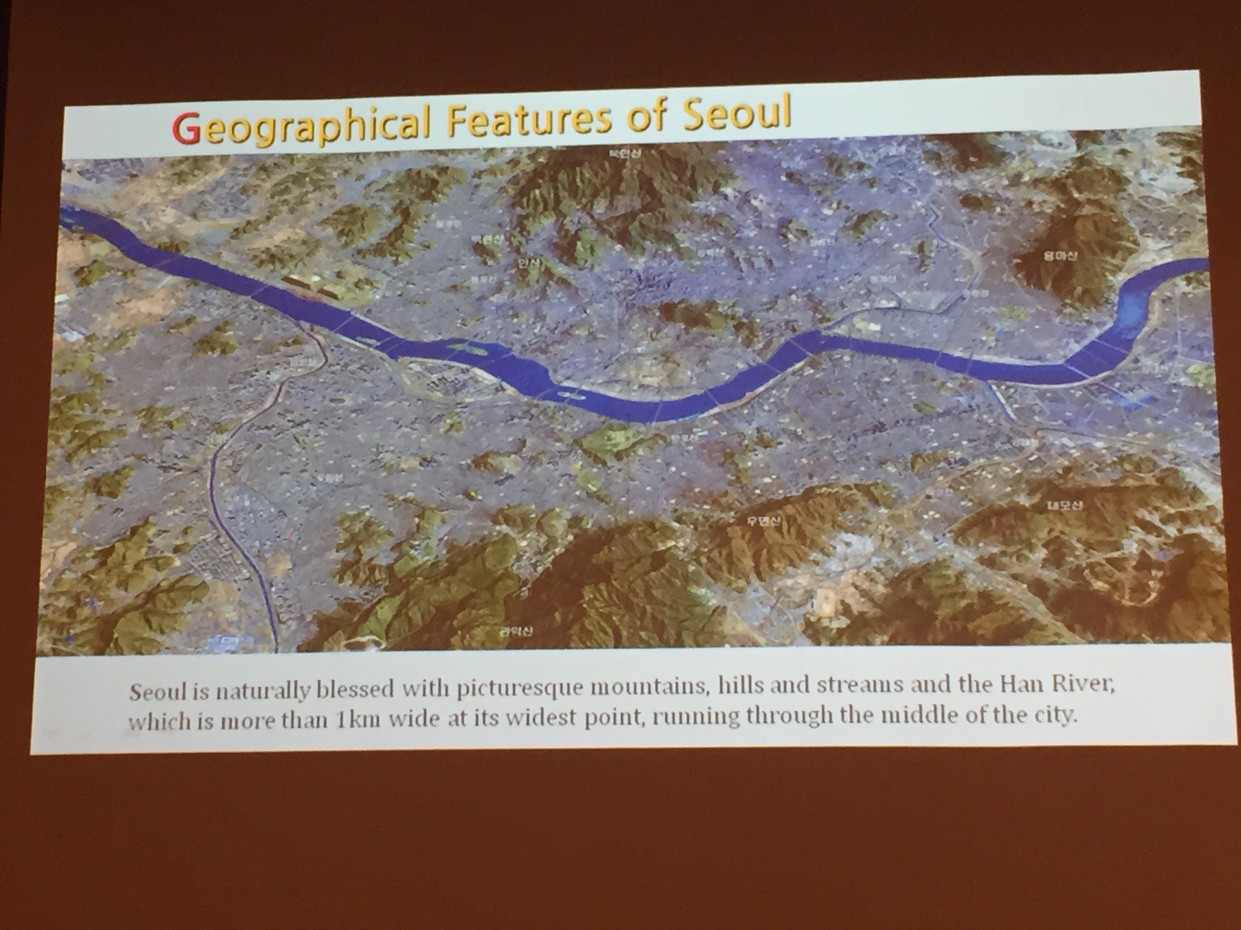

Seoul’s geography presented by Mack Joong Choi (Seoul National University) in The Seoul Experiment session, SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

Joong was one of a raft of local academics and researchers at the SIBAU symposium analysing what the curators dubbed The Seoul Experiment, in a session also eliciting a huge number of fascinating facts and insights about the future shape of the city’s communities. The sociologist Miree Byun (Future Research Center, The Seoul Institute) said that in 2014, the median age was 40 (in Tokyo, 44 years of age), therefore relatively young, but ageing rapidly going forward, with an increase in small households. Most senior citizens live alone: 2/3rds of them are women. There was income and education inequality, family stability decreasing, an unstable middle-class, class mobility is quite weak and people are becoming more conservative overall.

Seoul was becoming very multicultural, but both Byun and Myung Rae Cho, Department of Urban Planning & Real Estate, Dankook University, felt Seoul must become more integrated socially, underlining Mayor Park Won-soon’s emphasis on inclusiveness and sharing in city policies. Cho cited the distinction urban planner and social scientist Michael Douglass made between cosmopolitanism and conviviality if one is to achieve more citizen-centred cities. This avoided the assumption that multi-cultural populations automatically meant a city was cosmopolitan, in favour of an emphasis on how policy actually works in practice, with ‘a distributive justice vision of government’s role’, added Cho.

Bukchon Hanok Village, Seoul, 2015, © Republic of Korea.

Chang Heum Byeon, a housing specialist from the SH Corporation, explained that public agencies were asked to play new roles beyond just supplying housing, customized to local needs. Rental housing ‘can’t be featureless, one size suits all’. An integrated approach to public housing, integrating agents, spaces, functions and public policies, was needed, so the SIBAU needed to promote the new models ‘building several small communities to add diversity to the city’ Seoul is experimenting with. In the context of Seoul’s rapid growth, the basic unit of the ‘apart’ represented a synergy of financial structures and political systems, the DNA of the larger structure of the city as moderator of the planners’ session on day two, Francisco Sanin (University of Syracuse), put it.

For Choi it was a question in Seoul of further distinguishing ‘glocalisation’ and working out how to mobilise the city’s resources, prioritizing qualitative growth. Byun foresaw hard situations ahead during the period of low growth rates, and a need to find alternative growth models, one being a more friendly environment for manufacturing to survive in, and focusing on affordable housing. A time for remodeling, restructuring, refurbishing old areas including apartment complexes. Byeon said there were 1300 areas in the city to be demolished for new housing but the land should not be given to the private sector: the public sector has to show the way.

Zaera-Polo reminded everyone that SIBAU was intended to be a place to share knowledge focus across Asian cities, without prioritising nor conforming to any single, colonial-style model. He wondered how Korean policy makers geared towards big-scale planning would re-plan Seoul with priority for the smaller buildings and urban developments identified as important in the contemporary urban model of diversity. At the same time, in finding solutions to housing, water, air pollution and mobility, Seoul needed to be building up its identity and distinct potentials and qualities, drawing on its diversified, youthful culture, and in this way would best develop as a place for test marketing in the global market.

Indy Johar (Architecture 00), Contemporary Urban Technologies session, SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

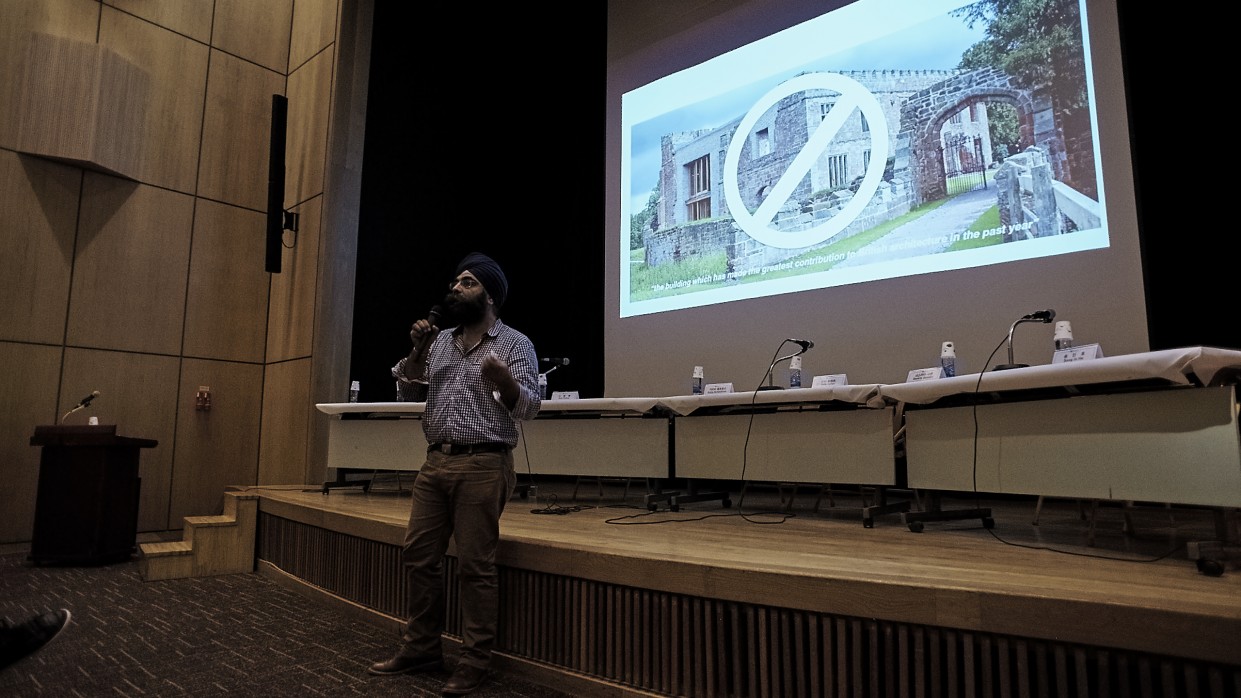

The question confronting SIBAU underlying contemporary urban technologies such as Big Data and ubiquitous computing was ‘how to make society’, said Indy Johar, architect and co-founder of Architecture 00. Building the new civic assets for the future was about empowering human agency and capital in a shift from real estate to real value, and from a state centric corporate economy to polycentric micro-massive economy. With a systemic focus, said Johar, a new meaningful system of urban financing and a multiplicity of actors, wicked challenges could be addressed. With the growth of co-working and co-making, an economy led by the many, financing systems rather than products was manifesting itself through decentralized innovation. New mega- yet anti-urban projects like Songdu City in South Korea add density but not urban quality, said Saskia Sassen (Department of Sociology, Columbia University). Globally a sub-prime housing market is expanding, with a rising amount of foreclosures, and knowledge had to breed laterally across neighbourhoods to enable a relative sense of autonomy by communities whose members, in such an open society, become hackers of technology.

Katja Schechtner (MIT Media Lab), Contemporary Urban Technologies session, SIBAU Symposium, October 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

This shift to open source urbanism, as Katja Schechtner from MIT Media Lab illustrated in her talk, was necessary to preserve the public good in an evolved incarnation of the welfare state with interactivity, but she was cautious about the idea of a singular ‘we’. Moderator Yehre Suh emphasized that ‘urbanism has been happening through the dispossession of all kinds of previous cultural, social and economic assets, so in what ways could technology redefine the ‘we’? Also, all open source, community-driven processes are fragile, physical and political, Zaera-Polo pointed out, and reliant on a more top-down, formal infrastructure provided by large firms and government. The question was how to reconcile that with aims for open source to be more widely generated socially.

Song In Ho (TBS Design Research Center, Seoul Design Foundation), saw Seoul’s smart mobility systems changing the previous top-down model to a bottom-up one, with more focus on interactive experiences between destinations. This was a less homogenous, more diverse system focused on the value between people. Seoul’s aims were similar to NYC’s: promoting equity and quality of life. Changing the paradigm towards semi-autonomous driving and ‘an Internet of moving things’ (including to collect garbage) involves the evolution of ‘human-ware meeting diverse needs through more seamless access. The implications for what the Biennale in Seoul exhibited therefore were clear: architecture should be presented as a flow of social knowledge systems, processes and institutional logics, said Johar. Seoul needed to experiment to discover neighbourhoods’ local knowledge systems as a starting point, in line with the ambition to be research-driven and socially inclusive.

Hans Stimmann (former Building Director, Berlin Department for Building and Urban Development), Urban Governance session, SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

In considering Seoul’s scope for experimentalism through, the SIBAU symposium therefore also needed to evaluate how far urban planning processes can be experimental and knowledge-producing. Global city trends and issues invariably deeply impact upon the planning of a particular metropolis. In what ways is this good or bad? These were questions posed by the symposium curators to the panelists of the second day’s session with city architects from Asia, Europe and Latin America. The insights about Yokohama, Shenzhen, Berlin, Barcelona and Medellín offered varying examples of leadership visions. Beyond the priorities by city architects and urban designers, and directors of the planning departments, the session tried to open out the notion of a Biennale as a device to regenerate the city closely related to the production of it. This theme is so central to the success of the future SIBAU that further roundtable discussions extending its focus are vital, in order to ferment the initial ideas put forward at the symposium.

Weiwen Huang (Shenzhen Center for Public Art), Urban Governance session, SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

In Japan from the 1960s, as Kuniyoshi Naoyuki, former Executive Urban Designer, City of Yokohama, from the Urban Planning Unit of Yokohama City University described, architectural proposals for cities, some made more closely with the regions, were implemented with increasing public consultation. Weiwen Huang, former Vice Chief Urban Planning, Shenzhen Municipal Urban Planning & Land Resource Commission, and one of the founders of the Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture, said that the reason they started the Biennale was the perceived inadequacy of architecture alone, and indeed the car-oriented model of urban planning, to face the complicated systemic challenges of the city. He would like Shenzhen to learn from the grassroots ideas of the informal urban villages within its territory.

As is widely known, the city as a collective political project expressed through all aspects of planning was fundamental to the evolution of Medellín in the last 15 years, explained Jorge Pérez, Director of the Colombian’s city Urban Planning Department. The idea was that the telecable networks introduced could be a catalytic element generating serious public interventions. The examples presented had a variety of impetus and historic timescale, and some achieved laudable results. But as the logic of the symposium was to go on to evaluate the experiences of other Biennale curators, this session had to draw to a close before fully analyzing urban design and planning as experimental practices influencing policy.

The City as a Global Asset panel discussion, SIBAU symposium, with Alejandro Zaera-Polo (Director, SIBAU symposium; Princeton University), Hyung Min Pai (University of Seoul), Minsuk Cho (Mass Studies), Mark Wigley (Columbia University), Beatriz Colomina (Princeton University), Aaron Betsky (Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesen), Joseph Grima (Space Caviar, Chicago Architecture Biennial 2015), SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU.Pilmo Kang).

Today we live in a ‘Biennialozoic Era’, according to the November 2011 issue of Domus, with a public biennale on show on any given day of the year. All the speakers in this final session agreed that the biennale still had great potential as a cultural medium, had to be unique, and to assert its identity as the laboratory for the city in which it was held. Aaron Betsky, Dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesin, curated the 11th Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2008 (Architecture Beyond Building), and the CollageCity 3D exhibit at the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture Shenzhen in 2015, promoting urban accretion rather than totalizing, in a way that needed a greater conceptual synergy. Betsky spoke in favour of independence from political and commercial pressures, and in asserting the identity of regions rather than cities.

Beatriz Colomina (Princeton University), The City as a Global Asset session, SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

Beatriz Colomina (Princeton University) and Mark Wigley (Columbia University) are curating ‘Are We Human?’, the 3rdIstanbul Design Biennale due to open on 22 October 2016, on the relationship between concepts of ‘design’ and ‘human’. Colomina conveyed her research project on blurred notions of public and private in an era of social media.

Terrace cafe at Ihwa Village, Seoul, 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

For Wigley, if cities have changed their meaning in ways that are hard to grasp, and need design as a form of magic, they are open to becoming ‘in-vitro experimental laboratories’. Of educational value to both designers and wider audiences, the biennale is an interface that ‘tries to produce a more stable image of design and the city..to soften and reduce the shock of a dynamic world’.

Joseph Grima (Space Caviar, Director with Sarah Herda of the Chicago Architecture Biennial 2015), © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

The advantages of networked design transcending individual authorship have most agency in cities today, said Joseph Grima, Director with Sarah Herda of the first Chicago Architecture Biennial 2015, promoting both the technical and aesthetic aspects of the idea of multiple authors. He agreed with Giancarlo di Carlo who emphasised ‘architecture is too important to be left to architects’ (di Carlo also regarded architecture as the ‘art of processes’, most apposite here). There were now 60 biennales across the world, 65% of which had been established in the last decade, and, as platforms for research on urgent topics, organized measured their success in the short term through media coverage and attendance numbers.

Grima’s presentation begged the question of legacy aims, which he did not articulate. While Olympic events have more commonly produced ‘white elephants’ (Athens, for example) or drastic changes in land use (as is the case in the build-up to the Rio Olympics), than even-handed regenerative legacies for their sites, biennales, being transient cultural phenomena, in common with festivals, could ensure urban policy legacies with the buy-in of local municipalities. They need to do that without diluting the magic of design, while ensuring the programme is true to its experimental ethos. Biennales should promote an interpretation of urban design that is genuinely co-created, as Grima advocated. Beyond that though, they should be about new and adapted systems, and about how the urban environment makes people feel.

Minsuk Cho (Mass Studies), The City as a Global Asset session, SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

The Korean architect Minsuk Cho (Mass Studies), who has curated many exceptional exhibitions including The Crow’s Eye View: the Korean Peninsula, the Korean pavilion for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, was clear and insightful in his two main thematic premises and advice. Firstly, a new architectural and urbanism biennale for Seoul needed to distinguish itself from the art biennale model most biennales are based on. With 10 million people, the reality of its urban environment was drastically different to that of Venice, and a Seoul biennale needed to ‘involve its vast and complex resources’ and be place-specific.

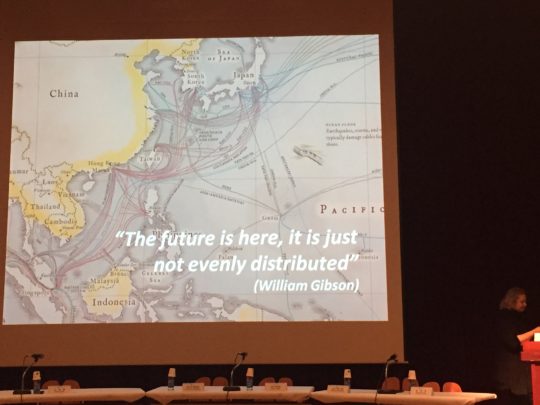

Cho wanted to exploit the notion of the country as a peninsula or bridge, between east and west, north and south, developed and fast developing. Placing attention on the developing regions would be fruitful as countries in the region shared similar histories of modernization bringing common urban qualities, ‘there has been a lack of exchange and support’. This would shift the histories of architecture and urbanism away from cross-Atlantic dialogues (and reliances).

Hyung Min Pai (School of Architecture, University of Seoul), moderates The City as a Global Asset session, with speaker Minsuk Cho (Mass Studies), SIBAU symposium, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

He also felt there needed to be a strong relationship between the different areas of the shared research carried out, and through network urbanism and urban acupuncture along nodes through the region, a distribution of focus could emerge. This was the kind of questioning that took place at the Rotterdam Architecture Biennale, for example. ‘We have about four architectural institutions and about twenty architecture schools, and there is so much traffic happening in the last ten years, which is shocking and there is no hub for it’, so this alone made the possibility of the SIBAU a ‘great opportunity’ for the Seoul Metropolitan Government. Specialists needed to be invited well in advance, otherwise it was just a city expo; the preparation time allocated by the biennale organisers for Venice and Shenzhen was far too short.

Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Dominique Perrault Architecture, 2008.

What kind of biennale laboratory, then, would be most conducive to a metropolis like Seoul? This final session, questioning of the role and identity of the biennale as a phenomenon, revealed variances in approach. Zaera-Polo made the point forcefully that SIBAU needed to experiment with new kinds of processes and experiences, rather than the norms of biennale autonomy, experiences and ephemerality expressed by Betsky. Wigley concurred: it should ‘disrupt the traditions of the biennale to be more productive’. The biennale had to explore the new reality of hybrid digital space, said Colomina who underlined the historic nature of pavilions as sites of architectural experimentation.

Grima had some frustration with the lack of overarching infrastructural and longer term investment in the biennale as an institution. Zaera-Polo thought that Seoul ‘represents an opportunity that probably does not exist in Chicago and other biennales’ and supported Cho’s outline of the future Biennale in relation to existing institutes of architecture. Both were in favour of an interaction with the specific conditions and realities of Seoul and the architectural scene in South Korea more widely.

While transcending the immediate context was important, the priority for deep local engagement and resilient, long-lasting institutional commitment was vital, said Zaera-Polo in his final wrapping up statement. SIBAU, as a knowledge-seeking vehicle, could be an opportunity for ordinary citizens, and, through this local engagement, appeal to a wider public to enable new processes. As HaeSeong Jae (former President, Architecture & Urban Research Institute; AURI) reflected in interviews with 20 experts staged prior to the symposium, ‘citizen participation should be actively promoted..(it) may result in a drop in architectural and administrative efficiency. However the social and political process of gaining citizen support is more important. This is how architecture can win the hearts of people.’

While regretably the series of interviews were not articulated as live presentations nor a public debate as part of the symposium, these local experts expressed a valuable consensus about priorities for Seoul’s adaptive planning visions for the coming years, ones that the SIBAU needs to embody and engage with. The critiques of mega-developments getting central stage without sufficient attention to community-focused schemes are familiar to many cities globally, but they play out differently from those in the west due to the rapid development patterns of Seoul, and metropolises like it. The huge scale of the city’s population means that a change in strategy towards network, acupuncture-oriented urbanism, fundamentally changing its ecology, would reap benefits for millions of people.

The SIBAU speakers and delegates visit the Seungsangga complex, Seoul, October 2015, © SIBAU/Pilmo Kang.

Seunsangga Arcade, Seoul, 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

A number of the interviewees attest to the city’s essential hybridism and a laissez-faire planning environment born of an intense period of modernization and ‘the indiscriminate adoption of West models (San Hun Lee, Konkuk University). A mix of informal planning, ‘organically interlaced with official elements’ (Yehre Suh, Seoul National University), makes it possible to see its ‘social ecosystem and dynamics’ like ‘urban tissue’, with spatial and social cracks’ (Suh). For Chang Heum Byeon (SH Corporation), Seoul’s rapid development meant that its framework was built fast ‘without much consideration for safety, design and functionality’..and with urban planning ‘limited to resolving urgent pending issues, legalizing, associating, or improving phenomena that had already taken place.’

Seungsangga Complex from across the street, Seoul, 2015 © Lucy Bullivant.

Therefore, how ‘fluidity and flexibility can be attained’ within the inherent ‘order’ of Seoul (Sang Hun Lee) was a key issue to be investigated. Currently, the focus by Seoul Metropolitan Government was on mega projects, said Sungjin Park (SPACE): the Seoul Station Overpass, Seunsangga Complex (the megastructure was the subject of a competition for a masterplan and programme to revitalize its pedestrian access and local industry) and Mapo Oil Reserve Base. He spoke for most of the interviewees in wanting policies and projects directly influencing citizens’ daily lives. Both he and architect Marc Brossa, however, cited the ‘growing number of small, social projects and housing projects’; ’higher interest in daily space’; connecting these to ‘more in-depth thoughts on ways of life’, and shift from tabula rasa projects to those intervening and remodeling (Brossa) and increasing attention given to urban sustainability.

Aside from the Seoul Plan 2030, which emerged from citizen participation, but remains distinctly top down, there needs to be newer forms of regeneration distinguishing themselves from past methods of redevelopment, agreed Ki-Ho Kim (University of Seoul). Jun-Bae Cho (SH Corporation) made a distinction between regeneration projects at the urban planning level and ‘neighbourhood-building projects’. With the latter, a much greater focus is placed on ‘the process rather than the purpose’, but he felt that the two needed to done with close attention to each other. All of these observations are a cue for the SIBAU to foster alternative policies based on qualitative measures of urban design and architecture (Soo Jeong Seo, AURI).

Moreover, an urban regeneration scheme that citizens can independently manage needs to be created, feels Sung Hong Kim (University of Seoul) because current publicly funded regeneration projects’ – are large scale and development-led and ‘led by non-citizen parties’, he said. ‘There is a need for policies that consider neglected and leftover spaces and public spaces’, said Jinyoung Lim (Open House). This kind of micro-level attention also needed to be given to a more balanced provision of housing to support regional urban regeneration and the city’s social system, said Chang Heun Byeon (SH Corporation). Byeon’s call for balance extends to city-wide development, and he wanted more equal focus on 7-10 nuclei in Seoul, rather than giving too much priority now to the Gangnam district south of the river, a new core of business with a very high standard of living some have likened to Beverly Hills in Los Angeles.

Lunch in Seoul, 2015, © Lucy Bullivant.

Breaking down the boundaries between architects and the public to create a closer encounter was viewed (Bross, Je) as a fundamental part of the next stage in Seoul’s evolution of its architectural culture. That would rectify the historic abandonment of architecture’s social role and neglect of urbanism and urban design, revisit the reflections of CIAM towards the roles of architects with regard to an urban agenda and democratize both architecture and urban design (Ki-Ho Kim, University of Seoul). It would also represent a genuine paradigm shift, it was widely felt (Kim, Lim, Park, for example), towards ‘a people-centred city’ (Je). ‘The Biennale should present opportunities for both architects and citizens to think deeply about agenda items related to Seoul’s pending issues’ (Brossa). Could it do that as well as develop the international competitiveness of Seoul’s architecture, wondered Nam-Jong Jang (The Seoul Institute).

The SIBAU needed to be a channel for building a common understanding of the city and architecture, and for sharing knowledge, said Sungjin Park (SPACE). This would expand architectural culture and enable citizens to recognize it as ‘daily culture’ (Junghyun Park, Mati Books) through new educational programmes for all ages. How the city should be built, the right to urban space (Park), universal housing, and the identity of architecture, were thought to be good themes, and ethical topics, for future SIBAUs, especially the discovery of identity in the context of a rupture between traditional culture and modern culture and the influx of Western culture to countries and cities in Asia (Nam-Jong, Lee).

Spring flowers, Seoul, 2014, © Republic of Korea.

‘There is truly no urban design in Seoul. Architecture replaces urban planning. Also, the city is ridden with urban development where architecture is absent’, pointed out Sung Hong Kim (University of Seoul). Because of this rift, he wanted a model that combines architecture and urban planning, one that promoted a network among Asian cities based on such themes. Considering Seoul’s conditions, this is a very sound proposition. Harnessing the input and energies of architects and citizens in developing new concepts for public space through the re-use, customization, generation and sharing of urban resources, with a range of public network partners (local municipalities, museums, social enterprises), above all, addressing holistically the challenges of urban sustainability together with all the major cities in the Asian network, and those beyond, are facing – each in their own ways – has to be a very high priority.

Rather than emulate past models of biennales with their higher degree of elitism, ephemerality and limited, short-term planning, it seems that Seoul’s biennale of architecture and urbanism needs to enable architectural culture and field-centred thinking to support an urban paradigm shift in which everyone in this multicultural city plays their part and mobilises their skills, whatever they might be.

Images by Flickr users reproduced under a Creative Commons licence.