1

Issue 1

1

Issue 1

Chengdu, 2012. Daniel Schwartz/U-TT Chair ETH Zurich.

Chengdu, China: big city symbiosis

Chengdu in central China has devoted itself to becoming a 21st century garden city. But Ebenezer Howard coined the phrase ‘garden city’ back in 1901, and Chengdu is undergoing a massive expansion through industrialisation and population influx. Between the rush of top down initiatives and quieter moves of bottom up speculation, what kind of evolution is being set in train?

Urban expansion among Asian mega-metropolises is nowhere more hybrid in its confluence of elements than in Chengdu, the foremost internationalized city in central China.

The nature of rapid, large-scale building and public works projects in Chengdu makes urban scenes such as this commonplace. Photo: Daniel

Schwartz/U-TT Chair ETH Zurich.

While in recent years attention has been on the Pearl River Delta, the influx of population of this provincial capital of the Sichuan Province in western China, with 14 million inhabitants, has risen from 2 million in 1980 and is expected to reach 30 million by 2042, making it a key urban centre of transformation.

City map engraved on doors of the Tianfu Software Park Visitor Centre, Chengdu, 2011, © Lucy Bullivant.

It was always known as a slow city, whose inhabitants are fond of their tea houses in the parks, but now in the race to compete with nearby Chongqing (population of 33 million; land size of Austria) its urban development rhythms have accelerated. Chengdu’s government is one of a number of players to join the drive to recreate the city as a hub of innovation, but at what cost to its identity?

Tianfu Software Park, Chengdu, model of developments, 2011, © Lucy Bullivant

There is substantial industrial restructuring, with Tianfu Software Park in the East Village Creative Industry Park, part of a burgeoning Silicon Valley-style district, including buildings up to 518 metres in height now manufacturing chips for every second laptop in the world; ongoing plans for farmers in rural villages to move to the city; a burgeoning CBD, and two megascaled cultural centres designed by Zaha Hadid Architects and Sutherland Hussey are on site in the centre of the city marked out by swathes of open land after demolition.

Preserving agricultural zones, Chengdu, 2012, ETH Zurich student team.

There are a myriad of intentions, and the subway is due to be expanded from 2 to 10 lines by 2020, but there does not appear to be an overall spatial plan. Without this, what happens to the identity of the city, busily preparing for its incoming citizens, in this state of hyper-rhizomatic development? Urban designers and Professors of Urban Design Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner at ETH Zurich Urban-Think Tank, who went to Chengdu in spring 2012 for their research project on Far East Asia, liken developments there to ‘the adoption of the Las Vegas model.’

A ‘bigging up’ of leisure space is certainly one side of it. Billed as ‘largest building in the world’, the 100 metre high New Century Global Centre, 500m long and 400m wide, big enough to hold 20 Sydney Opera Houses, is nearing completion, a mix of offices, conference rooms, a university complex, two five star hotels, an IMAX cinema, visitor attractions including a 5000m2 artificial beach and retail facilities. Across the road is the Chengdu Contemporary Arts Centre designing by Zaha Hadid Architects, under construction. Less glamorous, the Callison-designed, multi-block 24 City mixed use scheme is a standard retail podium topped by an office tower. While superficially an urban icon, it is just one more gated community. When it comes to living environments, existing market housing schemes in the city can be extremely pleasant, multi-functional spaces with lush vegetation, an ample room for tai-chi and other classes for residents and generous-sized children’s play spaces, but new high-rise social housing schemes are far too tall, and have a grim aspect, in spite of their colours, and little discernable scope for mixed use activities at ground level.

Professor Wenjun Zhi, Curator of the Chengdu Architecture Biennale, 2011, with colleagues at an outdoor suburban restaurant run by artists, © Lucy Bullivant.

Rather than being another generic 21th century skyscraper city, Chengdu could reinterpret its cultural traditions through a more passionate embrace of horizontal live-work environments. Evidence of local governments’ multi-focal approach is borne out at the artists’ colony of Three Saints Village, in the countryside just outside Chengdu, which officially received land from the government. The pastoral location is a favourite dining spot of Wenjun Zhi, Professor of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University, Shanghai, and Editor-in-Chief of Time + Architecture magazine, who was invited by the Chengdu government to curate last year’s Chengdu Architecture Biennale.

Chengdu suburban restaurant run by artists, © Lucy Bullivant.

Zhi is more in favour of the smaller scale, community developments, and Three Saints Village includes the tea houses that represent the city in microcosm, restaurants and studios and homes for artists amidst vegetable patches. That mix makes a lot of sense for Zhi, who focused in his exhibition on Chengdu as a world Garden City, a slogan the local government itself adopted at the end of 2009.

Maybe not as strong as Szechuan dishes, but Zhi’s exhibition gives a vivid taste of the inexorable changes taking place to the city. Chengdu sits at number four in population terms below Beijing (19.6 million), Shanghai (23 million) and Chongqing (28.8 million). Chips for everybody could be the mantra of this fast growing business hub, described by the Nobel Prize economics laureate Dr Robert Mundell as the development engine of the ‘Go West’ initiative, a benchmark city for investment in inland China and leader in new urbanization approaches. Its software and service outsourcing industry promotes the city’s transition from manufacturing to services has grown at a huge rate and today eleven of the world’s leading twenty software firms including Intel, Cisco and Foxconn are based in Chengdu.

Preserving agricultural zones, Chengdu, 2012, ETH Zurich student team.

Between July 1999 and July 2000 the city grew dramatically, moving built up areas out of the core of the city along roadways which radiate out of the city like spokes on a wheel, and expansion on the west side approaching the foothills of the Qionglai Mountains.

The government has given the software industry subsidies and grants for land use, and launched the 130m2 Chengdu High-tech Zone, 87m2 of which is Tianfu New City. This new science and technology district to the east of Chengdu’s Shangliu International Airport is the fastest growing software park in China, a key economic development zone free of factories in the Sichuan Province opened in 2005 and dedicated to the evolving software and service outsourcing industry and is coming together in four phases. It was one of earliest high-tech zones approved by the Chinese State Council – one of the first six pilots, driven by the country’s strategy to move development from coastal to central areas.

Chengdu Architecture Biennale, 2011.

Intensification of new industrial and cultural zones make questions of the future identity of the city as a place to live pressing. Holistic Realm, the exhibition Zhi curated for the Chengdu Architecture Biennale, considered the best ways in which man and nature could be integrated in this rapidly internationalizing city, one which is also seeing a top down bringing together of rural and urban citizens. ‘Change is the main topic in China’, says Zhi. ‘Life has changed and they need a new urban environment to match their new life. Sometimes you can see a historical presence but mainly for a commercial reason.’ He has reservations about the modus operandi. ‘The Regional Government has ‘a lot of programme’ and they need advice on ‘how to preserve nature in the suburbs, in the industrial zones. All the farmers moved to the city. The city enlarged so all the areas have changed to include high rise, and not in a good way.’ Urbanization ‘is an economic way all the city governments try to enlarge their cities to increase their GDP, so they view building as a way for economic development, while architecture is a field of art.’

Installation by architect Stan Allen at the entrance to the Chengdu Architecture Biennale, 2011

To stack up his arguments, Zhi created the Architecture Biennale as a localized, open platform with an international vision for ‘people to voice their opinions about city development against the backdrop of globalization.’ Projects by architects ranging from MADA (Qingyun Ma), Stefano Boeri, CHORA, MVRDV, Joshua Bolshover, Atelier Bow-Wow, Stan Allen, Groundlab, EMBT and Map Office, were shown alongside Chinese examples of agri-urbanism as well as propositions for green space distribution by many academic teams, including Jeffrey Inaba/Columbia University, along with other students’ projects chosen from 1000 international contestants.

Streetacre City by TAO Architects, an urban strategy for East Village, Chengdu, Chengdu Architecture Biennale, 2011.

Chengdu Architecture Biennale, 2011. Photo: Lucy Bullivant

The driving motive was to unearth research-based ideas for a 21st century interpretation of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept, taking on board Chinese cities’ current issues of high-density. Ha Li of TAO Architects’ Streetacre City urban strategy for East Village, by integrating rural and urban elements, seems to address the issue of farmers’ hopes for a new identity as citizens of Chengdu through a translation of the best of rural life in the city, a growing theme in urban centres globally. Above the grid of the street, a bridge with a vertically layered mix agriculture, recreational, commercial and recycling facilities where people can plant their own crops, run urban farms, exercise, and find social stimulation. The longstanding lifestyle in Chengdu epitomised by the image of the Chengdu dweller who likes to sit playing mahjong with friends, discussing work, does not need to be, and should not be, threatened by development ambitions.

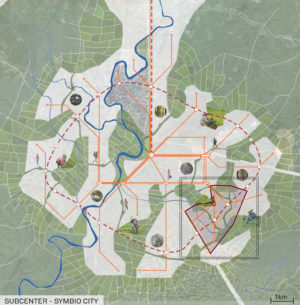

The new subcentre in the south relieves the city centre. Green space is cultivated between the subcentres to provide food and as recreation in the dense city, Symbiocity, ETH student team.

Streetacre City (a play on the name of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City) aims to adjust the ‘current monotonous urban life’ typical in China’s high density cities. Li spells out the symptoms: homogenous urban space caused by today’s land development system; a devitalized urbanism created by the lack of public space in ‘super-high density housing’, and subsequent traffic congestion and pollution. ‘A garden city needs to go beyond image, beyond a cityscape simply sprinkled with plants.’ He also doesn’t believe it should be ‘simplified as an exotic experience, or village life in another place other than the city.’ The advantage of Streetacre City is that it ties nature into ‘the pervasive infrastructure that makes the city what it is’, rather than creating isolated instances such as ‘balcony agriculture’ or ‘fake farmers’ restaurants in the suburbs.’

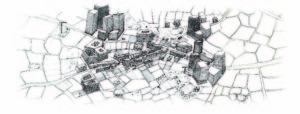

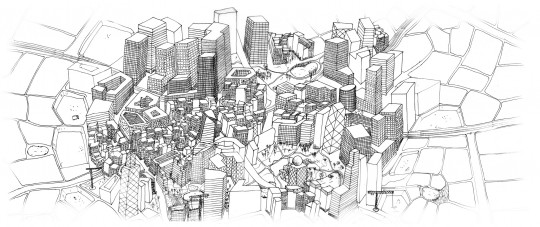

Symbiocity: vision for an integrated city, Chengdu 2012, ETH Zurich student team.

With an estimated 300 million people moving to cities in China in the next decade, the country ‘will have to rethink its current policy on social housing’, say Urban-Think Tank. They believe that China ‘must save its urban villages, protect its heritage of hutongs, move away from the car to the tram, keep the bicycle, and revive the culture of the street’. But they see a paradox in that because the approach to contemporary growth begins with a policy of erasure, that the resulting undifferentiated space lacks the necessary elements and resiliency.

Valuable land is preserved in the subcentre, Symbiocity, ETH Zurich student team.

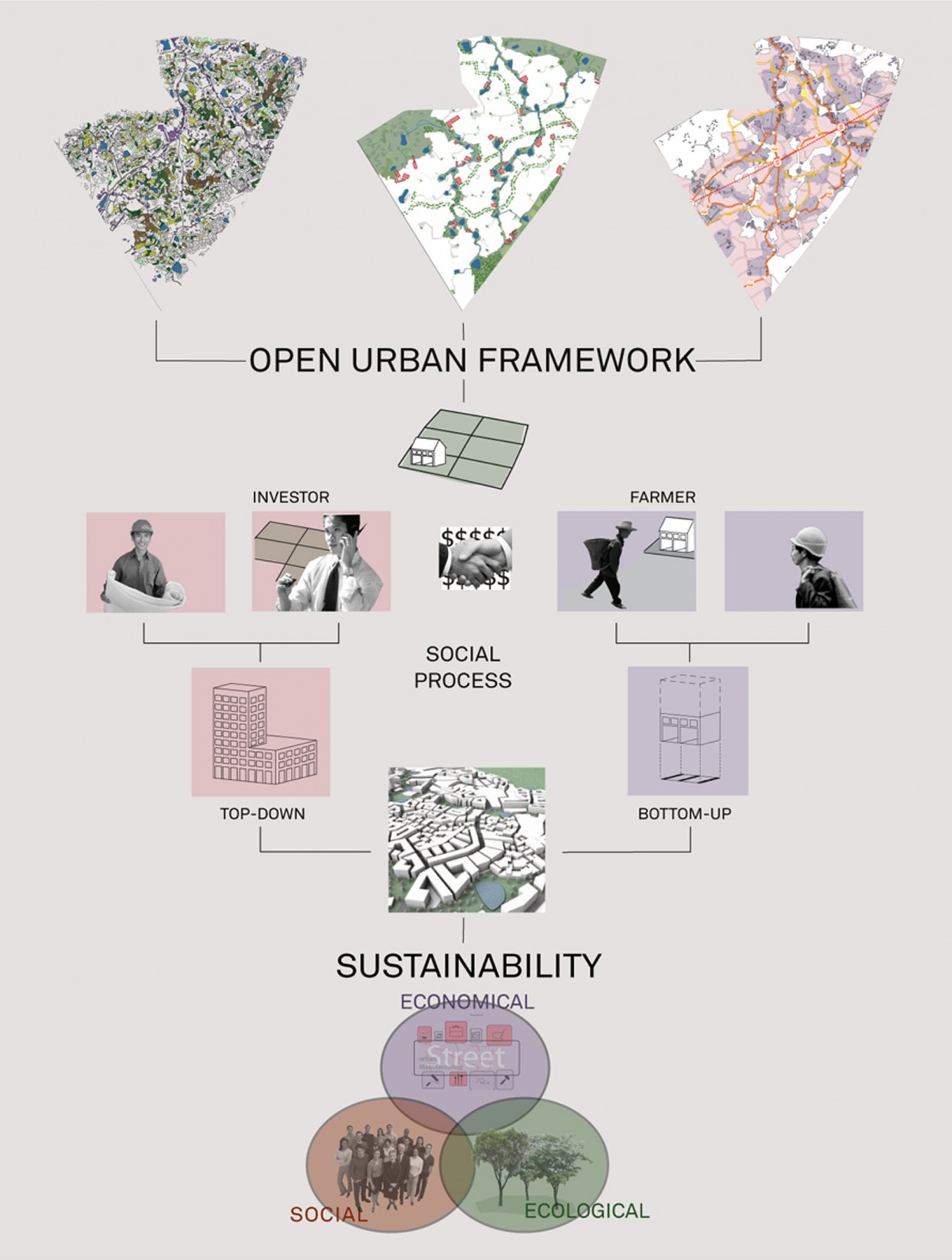

U-TT’s ETH students Carmen Baumann, Alessandro Bosshard, Julianne Gatner, Selina Mase, Louis Wangler and Nina Hug designed Symbiocity, which won the Vertical Cities Asia 2011 international competition organized by the International University of Singapore. Their response to the brief to design a district for 100,000 people in the suburbs creates synergy between areas planned by investors and those previously occupied by farmers which are developed in a more laissez-faire manner. The latter sell plots of their land to the former, creating a healthy social mix. Their work in the city convinced the group that, so long as it can also tackle ecological problems, ‘the model of bottom up areas next to top down areas is a promising scheme for Asian cities’, with ‘a balance’ between this and ‘the use-rights of people.’ All the answers are there, but will industry and government take them on board?

A time of lower costs and double digit growth is also a time for formulating creative plans that achieve balanced development with respect for the value of differentiated space. As Brillembourg, Klumpner and Professor Kees Christiaanse point out in the Introduction to S.L.U.M. Lab, Edition 7, Spring 2012, Asian Mode (published by the Future Cities Laboratory, ETH Zurich and FCL Singapore, SEC), ‘the city government has acknowledged that cultural production contributes to the added value’ of Chengdu. Asian cities differ immensely; on the other hand, while there are decreasing rates of food insecurity, relatively low violence and growing prosperity, ‘these regions must cope with increasing environmental problems, social disparity, labour exploitation and issues of political freedom’, so it is encouraging that ‘a shift towards a more qualitative from a mere quantative approach to the built environment and its public space can be detected in many places and on many scales.’

With thanks to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, London, and the Future Cities Laboratory, ETH Zurich, for their kind collaboration.

ETH Zurich, D-ARCH: Symbiocity Studio Project

Project Credits:

Chair of Architecture and Urban Design: Professor Kees Christiaanse

Chair of Architecture and Urban Design: Professors Alfredo Brillembourg & Hubert Klumpner

Studio Coordinators: Michael Contento, Nicolas Kretschmann

Student Team: Carmen Baumann, Alessandro Bosshard, Julianne Gatner, Selina Mase, Louis Wangler, Nina Hug

Not only ecological topics regulate the transformation process, Symbiocity, Chengdu, ETH Zurich student team.