1

Issue 1

1

Issue 1

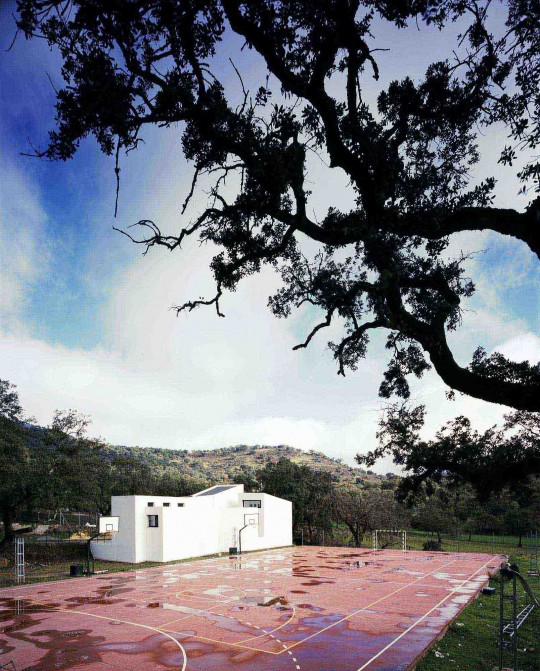

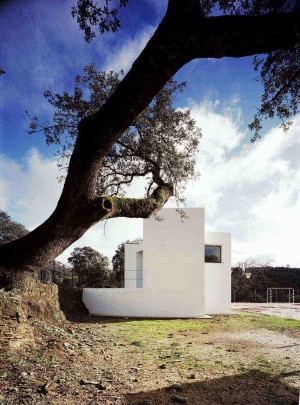

Medical centre, Almonster, south west Spain, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, 2007. Photo: Jesus Granada.

Spanish eyes on the urban and the rural: Canales and Lombardero

The Spanish architectural diaspora and slow down in commissions at home has dispersed numerous first rate practitioners and teachers around the globe. In 2007 the architects Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero came to London where they lead a Unit at the Architectural Association. At the same time they have retained connections to their homeland, and in recent years they have built a non-traditional patio house in Cordoba and a medical centre in a remote rural area of Andalucia that provoke discussions about innovation in local architectural identities.

Architecture is not any more about big seductive claims, but instead recognizing the plural and the diverse within what we normally consider as homogeneous, maintains Francisco González de Canales. In common with many younger Spanish architects, Canales and his partner Nuria Alvarez Lombardero have travelled well beyond their native land to find challenges. Their peers Ecosistema Urbano, Enric Ruiz-Geli of Cloud 9, AMID cero9 and others are based in Spain; however all of them maintain an involvement with the global system of architecture and avoid parochialism.

Canales & Lombardero, who founded their practice in 2003, live and work in London where they run Intermediate Unit 8 at the Architectural Association. In contrast to the older generation with established positions in Spain, they are happy to ‘rethink architecture in a more humble way, looking for opportunities that address and experiment with social realities’, says Canales.

Medical centre, Almonster, 2007, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, Photo: Jesus Granada.

Casa Priego + Lagares, Cordoba, 2008-9, Francisco Gonzalez de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero.

This humility is tempered by a polemical approach. The duo’s first two completed projects in Spain express their response to ‘a contemporary urban condition which cannot avoid its growing state of fragmentation.’ Casa Priego + Lagares, a ‘patio house without patio’ (2008-9), built in El Brillante, the first wealthy suburb to be realised in Cordoba at the foot of the Sierra Morena. The district was built at the beginning of the 1950s, mainly with chalets, some very fine by architects like Rafael de la Hoz, others from the 1980s rather pretentiously adopting a rustic hacienda style.

The architects’ house is distinct from everything else around it, and has attracted nicknames. It has two floors at the front, one at the back in a dual twisted form including a shed and a pavilion overlooking a small garden. Its big curved door-less front façade is a standard brick wall with a 5cm shell of sprayed-on concrete, 3.5cm width, over wood. ‘We chose this solution as we wanted something like a paper covering or thin veil, a continuous concave effect’, says Canales. ‘A brick wall would have been too heavy’. Positioning it as close as possible to the street avoided the typical way in which the suburban house – always set back – ‘dismantles the street’ by exposing the house but not allowing it to dialogue with its neighbours.

Casa Priego + Lagares, Cordoba, 2008-9, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, narrow patio and modern block. Photo: Jesus Granada.

Traditionally, dating back to the Romans, because of the heat, houses in Cordoba have been built with a cool central patio. The Moors continued in the same vein and the practice continues today, with people competing for ‘the prettiest patio’. Linked to all the rooms in the house, a patio is shaded, secluded but has fresh air. Typically this is where a retired grandfather will sit throughout the day, greeted by all who pass by, including the parish priest who may join him for a while.

The architects’ design liberates the house from this patriarchal structure. Instead, they have lightened its core, transforming the patio into a curvilinear skylight extending to the second floor from where the Sierra’s peaks can be seen. It tops a 1.5 metre wide zigzagged entrance circulation that double backs you into the house in a more concealed Arab than Roman style of entrance, so that entering the house becomes a ritual. The typical effects of specific patio houses are present, such as a plenty of light and ventilation and the lack of an aggressive exterior.

However, the typology is shaken up to open up the space to ‘new forms of living’. Instead of a patio, there are two pockets of open yard which enable transition into the more private ground floor. The small garden is framed and shaped by the house, and vice versa. The rear façade with its big windows in which profiles of plants can be seen, has what the architects call a ‘wrecked geometry’, giving a perception of ambiguity, floating, and of nothing stable.

Medical centre, Almonster, 2007, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, Photo: Jesus Granada.

Canales wants their design to be seen as distinct from architecture in the 1990s that created indeterminate programmes with ‘zones of intensity’, but also from the atmospheric architecture common around eight years ago, also dedicated to eliminating form.

Medical centre, Almonster, 2007, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, Photo: Jesus Granada.

Medical centre, Almonster, 2007, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, Photo: Jesus Granada.

An example of the former is the loft apartment created from the conversion of an old industrial building, which possesses the appearance of total freedom, and is only really suited to an independent single person. He argues that both traditions blur all limits and predeterminations to the point where it is hard to see how architecture can frame the possibilities of living together.

In place of this, the architects’ patio house combines conflicting typologies, for example, the pavilion in the rhomboid part of the garden, the small hut with a gabled roof in country house style housing the kitchen, and the open block of the modern villa at the rear. The superimposition of these different typologies is not to make a collage, but a way of relating things to ‘generate a zone of indeterminacy in between areas where limits and relations are clear and established’, especially noticeable at the core of the house where the open living room is. Inhabitants are free in their movements but still benefit from architectural boundaries. ‘It’s difficult to live without rules, and we wanted to find another way to live together.’ Moreover, contesting the way in which suburban housing in Spain tends to abuse the street, the house makes the public-private boundary more real.

The architects spent considerable time with the clients discussing a new relationship between the architecture of the house and the surrounding landscape, mirroring the days of Cordoba’s 12th century west Arabic Caliphate emirate, whose architecture embodied a sense of melancholy landscape. Francisco González de Canales takes his and his wife Nuria’s interest in domestic experimentation further in his new book, Experiments with Life Itself: radical domestic architectures between 1937 and 1959 (Actar, 2012), in which he studies a series of unrelated cases from the late 1930s to the late 1950s which pursue domestic self-experimentation by architects driven to the margins of social importance, such as Germán Rodriguez Arias, Ralph Erskine, Charles and Ray Eames, Juan O’Gorman and Alison & Peter Smithson.

The duo’s second completed project to date is a medical centre (built in 2007) in Almonaster north of the Huelva Mountains in the south west of Spain. Remote and underdeveloped, the region is not so far from the village where Luis Buñuel filmed ‘Les Urdes: Tierra Sin Pan’, his protest against poverty in the 1930s, which portrayed it as an isolated spot full of darkness and was banned by the authorities. ‘Although the situation has changed since then’, explains Canales, ‘there are still remains of this former situation.’

Medical centre, Almonster, 2007, Francisco Gonzaléz de Canales and Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, Photo: Jesus Granada.

The local municipality was given money by the Andalucian regional government to build a new medical centre: welcome news as for twenty years previously, it had only aided bigger villages and this small, sprawling settlement lacked both social facilities and the ability to lobby for new ones. But the architects initially offered the commission turned it down as there was no plot. It had to be situated between the 14 tiny villages, each with 14-150 inhabitants, but neither the municipality nor land owners could find any space for it. Four years passed and the architects, when consulted, decided to find a plot themselves: a modest, narrow strip between an outdoor sport facility and a small road.

It was a challenge to design the centre on this confined plot, and the architects’ structure is modest without any extras, in keeping with the rural landscape with its holm oak farms. Cheap and simple, its materials were produced on the site, which is rare in Spain. The facade is white, in order to be most economical and unadorned: ‘the details of the building are the people, the tree and the road.’ The architects use the context’s conditions to their advantage. ‘We wanted to shape a new rur-urban artefact which took as its material base the realities that surrounded it’, says Canales, ‘an indivisible composition.’

The building’s front façade echoes the language of the zebra crossing on the road, indicating its entrance, and it is shaded by an existing tree making curtains unnecessary, while the windowless façade facing an outdoor sports court is used by players to bounce balls off. The round indentations have built up a natural pattern. On the side where pigs are kept, their muddy undulations have also created shapes on the walls. Local building regulations made a 60% pitched roof mandatory, so they inverted the traditional gable roof to create maximum height in one of the sides of the doctors’ offices. That allowed high, large windows to be introduced enabling patients to see the profile of the mountains from their own secluded position.

It is clear that these projects have the identity of integrators of new collective experiences, taking advantage of their border conditions in individual ways. This polemical, experimental approach to urban space is evident in the duo’s current work – projects and competitions in Spain (they also recently became Directors of the Fundacion Arquitectural Contemporanea in Cordoba), but also Mexico and the UK. As Canales explains, ‘we want to grow in scale, become multi-functional.’

This feature was originally commissioned by The Plan magazine, and their version can be read here by subscribers who access it via the A-Z list of architects featured.

Experiments with Life Itself: radical domestic architectures between 1937 and 1959 by Francisco González de Canales, is published by Actar, 2012.