1

Issue 1

1

Issue 1

BIG and Ramboll, Amager Bakke waste-to-energy facility, Copenhagen, © BIG and Glessner.

Elsewhere Envisioned – Global Design NYU

Science, rather than art, is the steer behind a new touring exhibition on experimental architecture from New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, that argues for the opening of the sociopolitical borders dividing architecture from its landscape, and will add local projects whose flavour exemplifies this mindset at each future venue around the world.

Worldscape, Atmos, Stratford Town Hall, London, August 2012. Photo: Mat Smith.

Elsewhere Envisioned, an exhibition staged by New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study from 20 September-20 October 2012 at the NLA in London, took its title from the words of Maurice Merleau-Ponty in exploration of contemporary design that ‘is as close to the beyond as to things near’. According to its three curators, all of whom are Professors at the School, it is possible when we evoke ‘our power to imagine ourselves elsewhere’. What does this kind of deep social and ecological commitment actually entail as a cultural contract? Their assembled array of examples of experimental architectural research and conceptual design aims to convey how this is being done with maximum ingenuity and minimum compromise. Science rather than art provides the stronger steer in this context.

Terraform1, Future Brooklyn.

The practitioners have been chosen because they respond to the realities of urban contexts and challenges beyond comfortable myths or abstractions. Elsewhere Envisioned is a rare project to be seen in the context of the NLA, not least because the exhibitors are a diverse mix of 30 names including many practices based in Europe, ranging from the widely known BIG, to Fantastic Norway and Snohetta, to Jürgen Mayer H, winner of the last Audi Urban Futures Award, Rachel Armstrong, a London-based medical doctor, Raumlabor Berlin, UK practices like David Kohn, Atmos, Biothing and OSA, to emerging names such as Creus e Carrasco and HHF.

Specht Harpman, prairie House, 2011

As they are so invested in the concepts of the exhibition, the practices of two of the curators – Peder Anker, the historian of ecology and science, being the third – include work: Mitchell Joachim, who founded Terraform ONE, is working with science as a creative trigger; Louise Harpman and Scott Specht, Yale graduates who founded Specht Harpman in New York in 1995, with zero energy principles, as evidenced by their prairieHouse, a converted gas station. While Terraform’s Urbaneering Brooklyn 2110 is a comprehensive restructuring of food, water, air, energy, waste, mobility and shelter in a cyclical resource net, Prairie House is not based on a romantic vision of the American landscape, but on the straightforward recycling of outmoded structures built there, like the Texaco station canopy. This, the architects argue, has greater impact today than many active greening strategies.

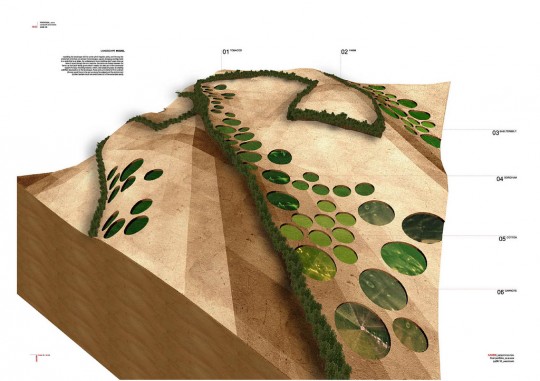

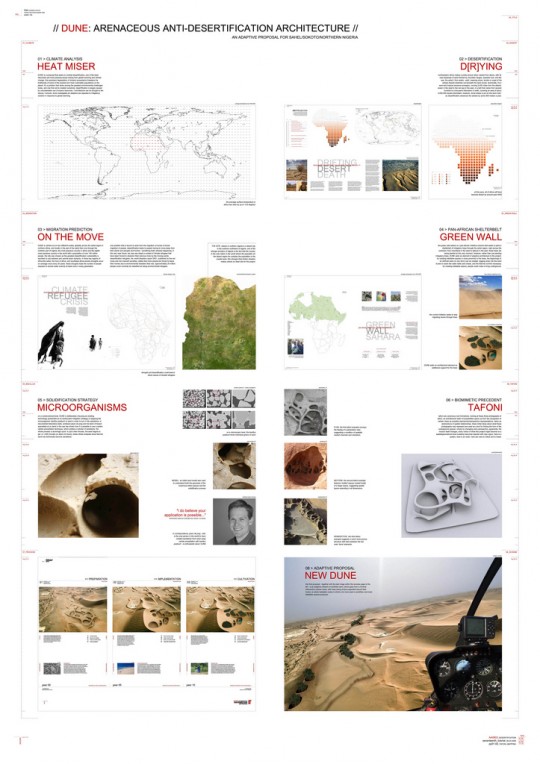

Magnus Larson, Alex Kaiser, Invincible Dune City, 2007-8

Magnus Larson, Alex Kaiser, Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture, 2007-8

A vivid mix of models, drawings, animations and projections, Elsewhere Envisioned is based on the idea that global design solutions can emerge without sacrificing local traditions, cultures and environments. ‘We propose a new GLOBAL – Global Local Open Border Architecture Landscape – design initiative as a remedy’, say the curators, whose concern is for a ‘language of design that can create proximity between individual responsibility and the current ecological crisis’, reformatting the separation between man and nature. Working with what is there, rather than avoiding reality, is a key generator of ideas. Doxiades+, for example, created a vegetation strategy that responds to the stark beauty of a Cycladic landscape, in an extension of the existing pezoules (agricultural terraces) and xerolithies (dry stone walls) on the site.

A myth they are keen to explode is that the widespread use of digital tools suggests a slow disappearance in regional variations in architectural design. ‘The practices are localized with broad interests’, says Harpman, ‘not driven by an aesthetic, but by biology’. A supreme example of this is the Invincible Dune City by Magnus Larsson and Alex Kaiser, formerly students at the Architectural Association, which strives for an invincible, rather than an invisible city of the future (the word used by Italo Calvino for the title of his 1972 novel). They convert existing sand dunes in the Sahara Desert, likened to Gothic cathedrals, into a 6000km habitable sandstone wall network – about the size of the Great Wall of China – constructed through microbial precipitation, as a defense against the potentially disastrous natural phenomenon of desertification. The concept also supports the Green Sahara initiative of 24 African countries to plant a sheltering belt of trees across the continent. Also featured is the work of Diploma Unit 16 at the Architectural Association, led by Jonas Lundberg and Andrew Yau, focusing on a series of adaptive, cybernetics-driven projects evolving alternative forms of biome-specific urban morphologies.

Nina Edwards Anker, Latitude Light, a solar lamp made for 41 degrees latitude: Living Lamp, the first prototype in the series, made of local recycled corten steel, 2010.

If a major risk to sidestep is the increasing dominance of environmental technologies in architecture often coming at the expense of local traditions, cultures and environments, also because they reinforce an objectifying rationale, then one way around this is to understand landscape in a geographical sense not from the outside, but from within. Nina Edwards Ankers’ Latitude Light includes three solar lighting projects, one for a basic module of interlocking cubes that can be used as a sauna room or screens; the others as landscape installations along the Bronx Greenway waterfront. Here, heating loungers with backs made of photovoltaic panels are set into a south-facing hillside. These are concepts which fit into a global system yet are sensitive to specific geographical features.

Interventions in urban sites that are complex and highly sensitive largely include participative processes, for example, with Code:Architecture and Eriksen Skajm Architects’ Fjell 2020, a long term project to introduce a new common and multi-purpose hall into the Fjell housing development dating from the 1960s at Drammen outside Oslo. BIG’s Amager Bakke waste-to-energy plant in an industrial area of Copenhagen near the city centre, due to open in 2016, replaces one that is 40 years old and does not use new technologies. Extending its social integration, and exemplifying their concept of Hedonistic Sustainability, BIG incorporate a ski slope, visitor centre and parklands.

Bloom, Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez, 2012, UCL Quadrangle, Victoria Park and Greenwich Cutty Sark site, 2012.

The curators maintain that but for major advances in design and construction technology transforming the scope of what architects can realize, some of the exhibits would only exist in the realms of fantasy. For example, Bloom, a crowd-sourced ‘garden’ (Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez), Worldscape, an inhabitable dining landscape (Atmos), both realized during the London Olympics in the summer of 2012 and discussed in more detail below, and the work of Jürgen Mayer H, for example, his Metropol Parasol for Seville.

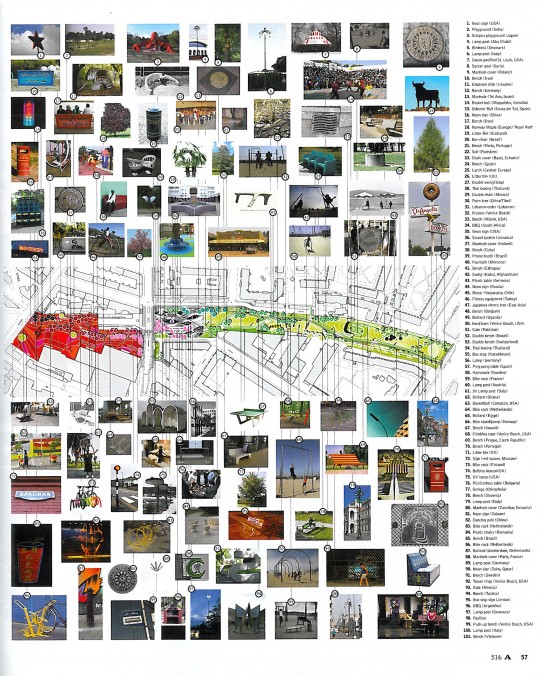

Superkilen urban park, Copenhagen, Superflex, Topotek1, BIG, 2011.

An exhibition about a fluidity about geography needs to feature reconfigurable projects, which it does, showing, for example, Aberrant Architecture’s Touring Theatre. As part of the wider mantra for transformed landscapes, the concept of the self-sufficient is also important, demonstrated by MMW’s Fhiltex and HOUSE dwellings, the latter being a mix of mobile, sustainable living without borders.

Then, above all, there is the notion of translocation: BIG, Topotek1 and artists’ collective Superflex’s Superkilen, a framework of new open spaces in a densely populated central quarter of Nørrebro in Copenhagen (Scandinavia features heavily in this exhibition) commissioned by the City and RealDania. It reworks a tactic from garden history: the translocation of a supposedly ideal place from far away in order to create a ‘home from home.’ Superkilen reflects the more than 50 cultures and ethnicities represented by residents living in the immediate vicinity. They were invited to nominate urban objects ranging from trees to playgrounds, benches to signage, which were either reproduced at 1:1 scale or brought to the site.

The design terrain of Elsewhere Envisioned is a potent field, and there are plans to tour the exhibition to other global sites where NYU has a presence – there are 50 in total, including in Shanghai and Abu Dhabi, where an intentionally reconstituted project including local work could expand the mix of gamechangers featured still further. To apply a more fluidly instrumental, yet bottom up approach to geography, the idea of a distributed practice, a federation, is an approach the curators strongly flag up, and accordingly it would have been good to see video interviews expanding on processes and the very logistics of working across global cultures in addition to the rich array of material that emphasizes how versatile many contemporary practices are in ‘envisioning elsewhere’ without erasing its essential qualities.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012. Photo: Stephen Tiley.

Worldscape, Atmos

Through his Worldscape installation, Alex Haw, the British architecture founder of Atmos, who trained at Princeton School of Architecture in the US, considers the science of geography, promoting a new way of thinking about a map and about global ethnic cuisines.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012, drawing.

A striking 15 x 6 x 2 metre dining table and seating ensemble for 80 people, it evokes immediate curiosity upon engagement with it as a functional object: does it represent the landscape of a specific area of the world, or all of it?

Worldscape, Atmos, Stratford Town Hall, London, 2012. Photo: Mat Smith.

Is it saying that the world’s continents and topographies should be interlinked? There is no orthogonality here: each person occupies a unique part of Worldscape’s ecosystem, sitting on its oceans, dining off its coastlines, illuminated by its cities and shadowed by the contours of its mountains.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012. Photo: Jonathan Perugia.

Worldscape uses the Equidistant Cylindrical map of the world, where all degrees are equal lengths in both directions. ‘Although it dates back to 100AD, it is still NASA’s digital map of choice because it clearly maps the world onto square pixels’, says Haw, who underlines its appropriateness for a dining experience by dropping its other name, Plate Carrée, into the conversation.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012. Photo: Jonathan Perugia.

Global Feast at Worldscape, Stratford Town Hall, London, August 2012, Atmos. Photo: Stephen Tiley.

As an inhabitable landscape, Worldscape is faithful to world geographic geometry, while being deeply unorthodox as a furniture archetype. Haw deliberates wants to ‘frame and prompt new, unprecedented dining relationships’, and this prompting stems from Atmos’s obsession with conjuring space from data and creating immersive ergonomic environments. The practice was also part of the team behind CLOUD, a giant floating observation deck of inflatable, LED-clad spheres at the London Olympic Park during the Games in the summer of 2012.

The table was made using digital fabrication from 4 foot wide sheets of melamine-faced plywood cut with ultimate speed and exactitude from the computer file. It derives from the map divided into 12, each strip measuring 30 terrestrial degrees in width, and forms a grid of 36 square modules of differently shaped land masses cut at 500 metre intervals which nonetheless link together to form one single, occupiable landscape. It uses all the world’s contours – from both above and below sea level – stretching their vertical relationship, a bit like an engineer’s section of a bridge, on order to best fit the body, explains Haw. Diners sit on an interlocked bench running the length of the trench 2 km below the ocean’s surface; they eat on the sea-level coastline – the universally recognizable image of a world map – immersed in a sectional cut through the world. Beneath, ocean contours cascade; above, arrays of mountains rise up, peaking at the Himalayas at 2.1 metres. Striated with longitudinal lines, the table’s surfaces are perforated with patterns of global cities, illuminated by a local light source for each area.

Haw’s highly crafted, sensual design is reconfigurable and he envisages other possible world organizations enabling ‘radical cartographic mashups’. The carved modules can interlink or detach to pack flat, and because their complex geometries conform to the terrestrial grid, longitudinal slices can be swapped and recombined to create new map forms, or parts of the table can be pulled apart to create café seating. Reinventing the typical dinner party setting on trans-territorial lines – literally – Haw is less interested in merely the ergonomics of dining’s comforting physical and emotional function than experientially provoking encounters with space, place and their encounter with unfamiliar kinaesthetics.

Worldscape was launched at the start of the London Olympics July 2012 with Global Feast, a dining experience with a menu created by Kerstin Rodgers, founder of The Underground Restaurant staged on all 20 successive evenings of at the Old Town Hall in Stratford next to the action, shifting progressively further east through all the world’s cuisines. An homage to London’s ‘world within a world, rich multiplicity of its population and extensive home restaurant food scene’, it was conceived by Latitudinal Cuisine, a collective culinary project Haw set up in April 2009, involving collective weekly dinners large and small popping up at a myriad of venues in London and beyond for which guests cook food from the latitude corresponding to the day of the year. Ranging from the Telematic, Eat with Art, Edible Edifices, Flower Food and World Christmas Cuisine, Haw’s concept, like Worldscape, is a powerful way to collapse distance and bring people together.

Bloom designers Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez with their team, London, 2012.

Bloom, Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez

Bloom, Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez, London, 2012.

‘Be playful and creative!’, as the artist-architect Constant Nieuwenhuys said in relation to his speculative utopian city, New Babylon (1959-74). Architects like the London-based Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez (Croatian and Chilean, respectively) want to move beyond bio-formalism, and play is one means to this end.

Bloom, Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez, London, 2012.

Alterable by the public, their Bloom project conveys the creativity of everyone who encounters it, for when they play and discover possibilities, the actual design emerges. Commissioned by the Greater London Authority as part its Wonder series celebrating the London Olympics and ParaOlympics during the summer of 2012, this urban toy in the official Olympics colour of neon pink, is a reconfigurable system of 60,000 recyclable plastic cells that is very easy to build, with attractive results developing fast.

Bloom by the Cutty Sark, Greenwich, London, 2-12, Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez.

Bloom, London, 2012, Alisa Andrasek and Jose Sanchez.

Its aggregation has a number of curved steel benches, which enable a number of connection points from which the structure could start growing.

‘We looked at LEGO, which is generic and universal, and other toys that could be assembled in different ways’, says Andrasek. ‘It’s a game, and, as in complexity theory, the simplest generic element can recombine.’ So in each of its three venues in London during the summer of 2012, the UCL quadrangle, Victoria Park near the Olympic Park site and in Greenwich next to the Cutty Sark, Bloom’s identity was adapted. Each of its cells is potentially a souvenir people can take home, a symbol of the event and of participation in the collective play Bloom encourages. The team has designed each of the possible connections between the cells, so through recombining the connections in each cell, or, as with music, following rhythms of repeating strings of the same connections, people can build a ring, a spiral, a distributed branch, among other things.

‘There is a universality to the cells, but they also have embedded biases and information encoded into them,’ says Andrasek, who initially asked students without any knowledge of the system concept to play and design freely with it, which gave the team awareness that it could be very easy for people to build. ‘No matter how randomly participants connect them, they will always exhibit recognizable behaviours. By following certain combinations intuitively you can invent a chair or a bench, or a canopy.’ Being so resilient and flexible, they also twist into new shapes and configurations, so people become active in ‘seeding new ground sequences that can be used as urban furniture or unpredictable formations.’ They have even considered adding a tagging system to the game, giving it a new identity with virtual tracking.

At each venue ‘people came, and while with art pieces, they can’t touch them, here they just went for it’, she adds. ‘The interaction is an energy source’. Initially it teaches them rules-based generative propagation, but then becomes something they can build themselves.

Bloom will be shown in further UK and international locations to be confirmed in 2012-13. Further details on the Bloom website.