1

Issue 1

1

Issue 1

Cybergardening the city

Cybergardening the city: ecoLogicStudio in Milan

The Architectural Association’s recent Visiting School based at Milan’s Spazio FMG per l’Architettura led by Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto from ecoLogicStudio, London, sought to create new systemic models imagining new agro-urban design prototypes.

Cybergardening; discussion with (L to R) roundtable guests Aldo Cibic and Richard Ingersoll and Visiting Directors Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto, July 2012.

Characterised for many centuries by the ‘marcite’ (water meadows) agricultural system, what operational identity will Milan’s future urban agricultural landscapes take in the 21st century? What new sustainable system is going to prove worthwhile, and how can citizens be brought closer into this eco-architectural vision? These are urgent questions for a city preparing for the EXPO in 2015 with the theme ‘Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life.

CyberGardening the City, the Architectural Association‘s Visiting School in Milan, codirected by Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto of ecoLogicStudio, architects and teachers at the AA, was held in the summer of 2012 at the Spazio FMG per l’Architettura, Milan, in the form of a 10 day workshop. The 25 international students participating went to Parco Sud in the south of the city to research five very different farms (cascine), talking with farmers and exploring their landscapes and facilities. Their motives and agenda were to create new systemic models imagining new agro-urban prototypes: an eco-architecture to help facilitate new urban cultural patterns that strengthen, and are strengthened by agricultural values and practice.

Gardening Cyberricotta farm, Spazio FMG, July 2012.

Discussion about Cyberfrisona farm, Spazio FMG, July 2012.

There are multiple scenarios to consider: firstly, agriculture within the city, more traditionally in the peripheral areas and in abandoned industrial spaces (as evidenced in the contemporary reinvention of Detroit). Milan also needs a better relationship with its surrounding smaller towns. So ecoLogicStudio’s focus is timely. Before the workshop they developed their concept of the Cybergarden City to give the students’ projects a design framework. It ‘represents a new agri-urban terrain, a meta-landscape for the spatial unfolding of key urban supply chains. Each food and energy resource negotiates the occupation of this meta-landscape generating new productive networks’, they explain. ‘Urbanity is allowed to emerge as a collection of new practices connected with the resolution of the conflictual dimension latent within the production of the critical resources necessary to guarantee the future self-sufficiency of our cities and regions.’

Cybergardening exhibition at Spazio FMG, Milan, July 2012.

‘Maybe the new urbanity – the fourth scenario – is where the boundary of the city will disappear in the countryside and the countryside becomes part of the city’, Luigi Nefasto, one of the participating students, feels. The culminating roundtable with Stefano Boeri, architect, urban planner and Milan’s Councillor of Culture, Fashion and Design, Aldo Cibic, architect founder of Cibic & Partners, Matteo Gatto, Director of the Thematic Spaces of the Milan EXPO 2015, Richard Ingersoll, Professor of Architectural History at Syracuse University in Florence, Luca Molinari (Director of Spazio FMG), Pasquero, Poletto and myself drew to Spazio FMG a good audience of locals, including one of the farmers and media representatives. The debate brought home just how applicable this process-based design approach could be to other global scenarios in which there is a need to bond farming cultures and the city, as well as to Milan.

Making Primo Sale cheese workshop, Milan, July 2012.

For their research and development the students undertook digital mapping through a self-devised interface based on the social media network Twitter to breed a new system of consumption points of locally produced agricultural products – milk, cheese and cereals. These are intended to function as socio-cultural attractors within the imagined civic ‘cyber-garden’. EcoLogicStudio use not only QR codes as locative media sourcing information via mobile phones but also the socially driven Twitter. Using the agency of people at various urban locations in this way, rather than streets and buildings, is a new way to investigate the city as part of the making of an urban plan.

Cyberricotta exhibition at Spazio FMG, Milan, July 2012.

Moreover the students’ proposed synthetic models – which draw on and reinvents the notion of a ‘filiera alimentare’, or food supply chain – are a highly innovative approach to urban design. To understand this more profoundly, they were tutored in the shaping of a critical written narrative: their own independent viewpoints on the agro-urban scenarios and their contemporary cultural, economic and technological factors, with each of the three groups producing their own op-ed. The first group, cyberricotta, with Katie McClure narrating, have this to say:

Cyberricotta farm, Spazio FMG, Milan, July 2012.

Speculative forays into food production and alternative farming methods are ripe for discussion. While we are not completely divorced from the knowledge that our food is born somewhere in nature, and despite living in increasingly hybridized city environments, our inability to demystify rural processes and understand how they relate to our bodies and lives is largely inhibited by the fact that we still see food as something that happens between the ‘urban’ city and the ‘rural’ farm.

Cyberricotta, detail of prototypical model, July 2012.

On a mission to better integrate locally made cheese into Milan’s nutritional consciousness, we found ourselves guilty of antithesising many related spatial concepts: urban/rural, near/far, digital/physical. Indeed, at the outset of our work we despaired that the current relationship between city dwellers and the food we consume is a passionate yet somewhat dysfunctional one.

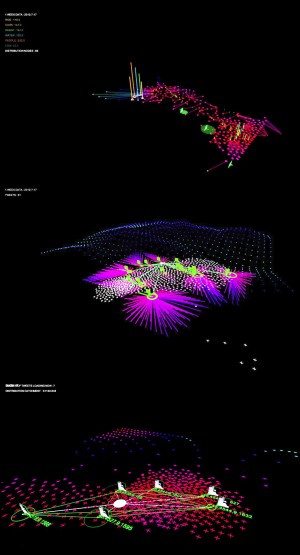

Cyberricotta: mapping the users’ Tweets, July 2012.

Wouldn’t it be great if the existing cheese production cycle in Milan could somehow lend an insight into how we might reconfigure the Milanese food network to create a more transparent and participatory culinary consciousness? A production cycle embedded in the city’s existing social situation that would feed itself by responding to its own natural metabolism. What if we were to simultaneously play host and guest to a sustainable, citywide dinner party of sorts, where urban, rural, digital and physical factors brought something to the table to flavour a truly organic local food revolution?

Scenario of self-organisation supply chain for milk, cheese and rice, Cyberricotta, July 2012.

By making Primo Sale cheese in Cascina Ca’Grande, a peri-urban farm, as a group, taking it across the city and eating it together in central Milan, we assumed the roles of producer, distributor and consumer all in one day. This ethnographic, empathetic approach, deconstructing both the literal and social components of cheese culture, and using QR codes, helped us identify lots of potential opportunities for participation and integration.

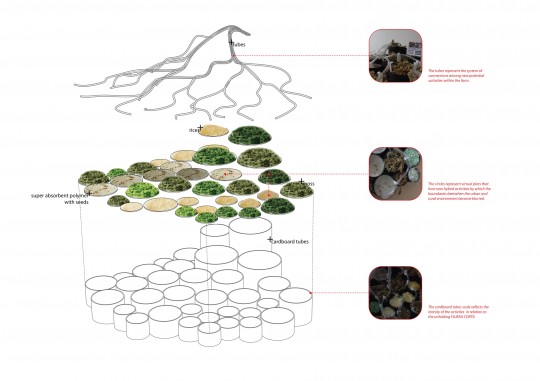

Our experiential overview of how people relate to the farm rated its scale and form large in structure with many access points, strengths that can built on further. Our reimagined cascina possesses three main systems: crops, cheese production and the existing heritage site. Its resilience, much like that of the human body, is dependent on their homeostatic ability to recognise and respond to challenges presented by Milan. The crop growing system is sustained by a biogestor and water recycling centre, which fuel the farm via a closed resource loop. Crops feed the cows necessary for the cheese production cycle, which, aided by a cheese market, resuscitates the old heritage site into a lively, contemporary hub for community activity and engagement.

Silos, raised above the ground, create volumes of space beneath the farm where people might congregate and flow. The farm’s overall height is extended by a biodigestor: functional and symbolic, it is a contemporary evolution of the old cathedral spire. An education centre onsite teaches people about cheese production as it relates to the farm’s heritage and current nutritional context. ‘Cheese meditation’ promises relaxation and well-being through direct engagement with the farm’s activities.

Reflecting on the contemporary farm as a new site of tourism and entertainment, we think that GPS, location-based activities could be very relevant as a modern method of urban orienteering and exploration. Visitors might extend the environment of their visit into a rich, virtual space through participation, syncing their multi-sensory media to the farm’s GPS location while moving in and around the physical territory of the farm, technologies which allow us to layer their multiple farm experiences online, creating an evolving bank of memories that could be tapped into in real time or in the future.

We have an abundance of digital mapping tools at our disposal, many integrated into online social networks available to the wider public. Digital and online technologies clearly possess the ability to overcome and enhance physical space, but the role of digital and generative processes in applied architectural development remains critical.

Using Twitter mapping, we simulated a consumer-driven model of the city encompassing the new cascina evolving in real time as we collected more data. QR code campaigns, Twitter and Processing fused to visualise existing cheese consumption points in central Milan, making use of quantitative data (how much cheese and where) and qualitative data (why cheese, and how we feel about it). Continued over a longer period, how might a map like this also enable designers to controversially speculate about future patterns of activity and development?

In this virtual context, food networks, of which cheese production is just one of its many inherent cycles, could fuse with other city systems in such a way that a city is advanced by a seamless integration between all of its elements.

In cyberGardening, smart phones and digital mapping software are as much tools of the trade as overalls and tractors.

Cyberfrisona research and development, Milan, July 2012.

The cyberfrisona team now tell their story:

Cascina Campazzo, situated in Parco Sud district of Milan in the future agricultural park of Ticinello – is totally surrounded by the city, just five minutes walk from the train station. It is not easy for the farm to survive here between the residential and industrial buildings. Established as a village in 15th century it was surrounded by fields and a lot of people lived and worked there. Nowadays few people live here and breed 130 cows, calves included. Andrea Falappi, the owner of this farm and the president of D.A.M. (Distretto Agricolo Milanese), feels that ‘The rural system which took place in Milan in recent days seems to open up the opportunity to see the work of a common front made by local and farms in the area, with the specific objective of reestablishing a direct relationship between country and city where you enable the first to serve the needs of the second from the social point of view, scenery and food.’

Final adjustment to Cyberfrisona farm, Milan, July 2012.

Our team has focused in our research and development on the production methods and consumption of milk, and when we visited Cascina Campazzo we discovered that there is a disconnected relationship between citizens and the farm. In the 1960s Italy experienced a big urban migration. A lot of people moved from villages to the city. They wanted to transform their lives and mostly found signs of rural agricultural life in the city incompatible with their dreams. Now there is a greater acceptance. However, right up to the present day we got the impression that the farm has been surrounded by an invisible wall, making citizens feel disconnected from its life. This is due to many reasons: there are not enough milk distribution points in the city, and also, for the visitor, it’s not easy to find the farm.

Considering this scenario, what if all citizens could get fresh milk directly from the farmer, saving them time but also involving them more directly in the life of the farm? We decided to analyse this farm from what we call a ‘cyber’ point of view. We collected a lot of data about the city, its population, and the distribution chain in this farm. We wanted to create completely new solutions to refresh the validity of the long established ‘filiera corta’ philosophy, which means the very special, confidential relationship between the customer and the farmer. This traditional process of consumption is practically lost now. But these steps are not enough and finding ways of increasing the productivity of this farm is particularly important for the renaissance of the urban-rural relationship.

So we set ourselves the challenge of renovating a traditional farm in the modern context. This could appear to be a two-edged sword: when people think about an urban farm in contemporary conditions, they usually imagine a scene from the pastoral world, in which everything is subordinated to the laws of nature as created by human beings. On the other hand, the immediate associations of the term of ‘a technologized farm’ are not very pleasant. A common cliché is that technologies in the context of a farm and of nature seem aggressive. However, at the same time, new architecture in farm settings, for example, farm shops, often merely look ecological without any change in their essential typological function.

Gardening Cyberfrisona farm, Milan, July 2012.

An alternative possibility could save the traditional structure functionally zoned and evolved naturally over many centuries, but at the same time constitute an ideal machine for today’s needs, a device in which technologies exist for the benefit of society and for the preservation of nature and its resources.

These days there is an interesting tendency: we have access to many innovative open source technologies offering possibilities to surpass the limits of perception, and we are currently searching for ways to apply these. For example, during our research we used Twitter to create a network which would enable the display of invisible communications between farms, distributors and buyers. At the same time, new ecological architecture should take on a revival and restoration function in this context. Nowadays in large cities there are lots of empty, abandoned spaces. They have already passed down a chain from the rural to urban, from the urban to post-urban. these deserve become new ecological spaces.

Cities should not inadvertently take a step back to the past. In building our narrative we tried to recreate an image of a farm which conserves an existing ecosystem, while increasing greatly its resources, as a green force which could grasp and revive these abandoned sites. We regard our design as a universal solution, one that will help to enable sustainability, not only for Cascina Campazzo in Milan, but for any farm anywhere in the world.

Final adjustment to Cybercereals farm, Spazio FMG, Milan, July 2012.

Finally, the third, cybercereals team recounts their story:

‘On our farm, one hectare of crop could feed four cows for a year, while in other places, it normally needs eight hectares of crop. This can be done because of marcita’, says Andrea Falappi, the owner of Cascina Campazzo, a farm located on the edge of the city of Milan. Marcite, or water meadow, is one of the oldest techniques of using liquid wastes for irrigation and fertilization invented in Milan and first used by Cistercian monks around 1138. Liquid wastes were collected in the canal and diverted into cultivated areas to fertilize the meadows. The water, which was improved by hot domestic effluents, flowed in covered ditches and advanced the plant growth in winter. Marcite has been perhaps the most advanced cultivation techniques, solving the problem of productivity, density, and unfriendly thermal conditions, which still are applicable. But it is rare to find another farm like Cascina Campazzo that uses this ancient techniques, largely abandoned now.

Cybergarden City, prototypical neighbourhood, July 2012.

Falappi has a vision that farmers can become guarantors of the authenticity of farmland. He believes that with their work and upkeep, farming land can be given a new fully nurtured identity. This notion of authenticity of the land has focused our attention, and we decided to start our project from this idea.

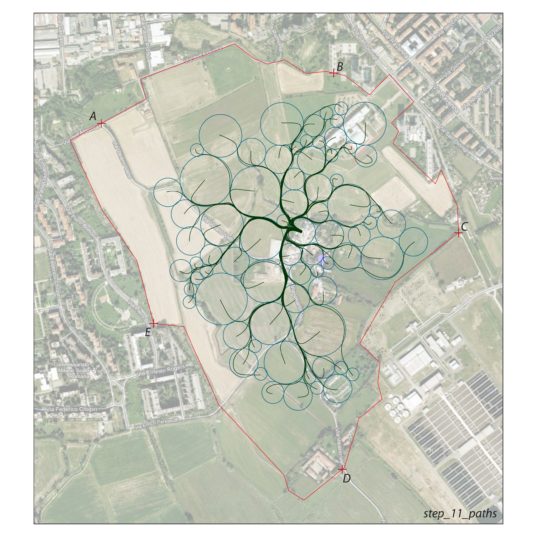

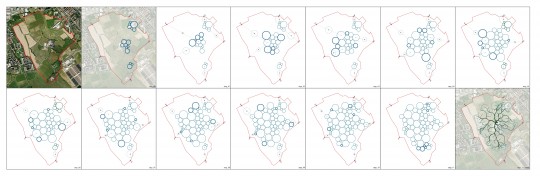

Cybergarden City: connection paths, July 2012.

We regard the activity of cultivating meadows to produce food for people as the authentic element in farming. So, in response to the current density problem of the city, we decided to start our own farming activities, cultivating data instead of meadows.

Cybergarden City: urban growth, July 2012.

We called our project Cybercereals, looking at the whole food chain of cereal production with marcite techniques around the site of Cascina Campazzo. How many resources and spaces are needed to feed people? In analysing the flow of resources in a chain composed of people, wheat, corn, rice, cow (organic waste for fertilizer) and water, we discovered the efficiency of the production cycle. Cybercereals is about feeding the people in the city. We calculated the amount of wheat, corn and rice that people need, and at the same time considered the quantity of water and fertilizer needed to grow the plants. Our new prototype is an artificial landscape of data extracted from the cultivation activities of the marcite presented in both physical and digital platforms.

Cybergarden City, aerial view, July 2012.

Our physical model is composed of a food producing and consuming cycle, used as the basis of a digital model in which the composition of data fluctuates according to the relationship of production and consumption points of cereals. In this case, we’re using the help of social media to collect data from the consumer by putting QR codes in the packaging of the cereals. This digital tool shows us real time accumulated point in some spots, and indicates the level of interest of consumers, which can help us to set up a new basis of artificial landscape in the future. Just like Falappi, who is enjoying his double life as farmer and citizen of the city, we enjoy our roles as farmers and designers, trying to cultivate data about resources and spaces relating to agricultural activities and to thereby create a more sustainable model of farming in the city.

This feature was originally published on Domusweb in Italian and English versions, 11 October 2012.

Workshop credits:

AA Milan Directors: Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto, ecoLogicStudio

AA Milan Tutors: Andrea Bugli, Lucy Bullivant, Immanuel Koh

AA Milan Scientific Committee: Luca Molinari and Simona Galateo

AA Milan students:

Marco Poletto (R to L), Lucy Bullivant, Luca Molinari, Stefano Boeri and Aldo Cibic at the Cybergardening roundtable, Spazio FMG, Milan, July 2012.

CyberRicotta:

Andre Figueiredo (Brazil)

Katie McClure (UK)

Luigi Nefasto (Italy)

Jonathan Sutanto (Indonesia)

Ismet Hakan Yarman (Turkey)

Hyunjin Yoo (South Korea)

Claudia Pasquero and Matteo Gatto at the Cybergardening roundtable, Spazio FMG, July 2012.

Stefano Boeri and Marco Poletto discussing the Cybergardening projects, Spazio FMG, July 2012.

CyberFrisona:

Amaia Arana (Spain)

Elena Fadeeva (Russia)

Monisha Prakash (India)

Melanie Sugiarti (Indonesia)

Beatriz Villahoz Herrero (Spain)

Discussion about the Cyberfrisona farm, Spazio FMG, July 2012.

CyberCereals:

Anita Halim (Indonesia)

Daria Sheveleva (Russia)

Patricia Silva Ojea (Spain)

Khushboo Sonigera (India)

Victoria Eugenia Soto Magan (Spain)

Special thanks to:

Iris Ceramica FMG Fabbrica Marmi e Graniti

Spazio FMG per l’Architettura, Milan

Comune di Locate di Triulzi and Diego Torriani

Comune di Pieve Emanuele

Commercarta Srl

Tenax Srl

Cascina Zipo, Zibido San Giacomo, Marco and Elena Zipo

Cascina Forestina, Alvise and Niccolò Reverdini

Cascina Campazzo, Andrea Falappi

Cascina Cornalba, Ferdinando Cornalba

CityVision Mag, Francesco Lipari