1

Issue 1

1

Issue 1

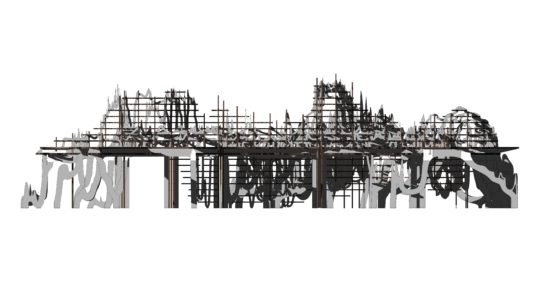

Worldscape, Atmos, Stratford Town Hall, London, August 2012. Photo: Mat Smith.

Worldscape: Atmos

Through his Worldscape furniture installation, Alex Haw, the British architect founder of Atmos, who trained at Princeton School of Architecture in the US, considers the science of geography, promoting a new way of thinking about a map and about global ethnic cuisines.

Global Feast at Worldscape, Stratford Town Hall, London, August 2012, Atmos. Photo: Stephen Tiley.

A striking 15 x 6 x 2 metre dining table and seating ensemble for 80 people, Worldscape evokes immediate curiosity upon engagement with it as a functional object: does it represent the landscape of a specific area of the world, or all of it? Is it saying that the world’s continents and topographies should be interlinked? There is no orthogonality here: each person occupies a unique part of Worldscape’s ecosystem, sitting on its oceans, dining off its coastlines, illuminated by its cities and shadowed by the contours of its mountains.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012, drawing.

- Worldscape uses the Equidistant Cylindrical map of the world, where all degrees are equal lengths in both directions. ‘Although it dates back to 100AD, it is still NASA’s digital map of choice because it clearly maps the world onto square pixels’, says Haw, who underlines its appropriateness for a dining experience by dropping its other name, Plate Carrée, into the conversation. As an inhabitable landscape, Worldscape is faithful to world geographic geometry, while being deeply unorthodox as a furniture archetype.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012. Photo: Stephen Tiley.

- Haw deliberates wants to ‘frame and prompt new, unprecedented dining relationships’, and this prompting stems from Atmos’s obsession with conjuring space from data and creating immersive ergonomic environments. The practice was also part of the team behind CLOUD, a giant floating observation deck of inflatable, LED-clad spheres at the London Olympic Park during the Games in the summer of 2012.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012. Photo: Jonathan Perugia.

The table was made using digital fabrication from 4 foot wide sheets of melamine-faced plywood cut with ultimate speed and exactitude from the computer file. It derives from the map divided into 12, each strip measuring 30 terrestrial degrees in width, and forms a grid of 36 square modules of differently shaped land masses cut at 500 metre intervals which nonetheless link together to form one single, occupiable landscape. It uses all the world’s contours – from both above and below sea level – stretching their vertical relationship, a bit like an engineer’s section of a bridge, on order to best fit the body, explains Haw. Diners sit on an interlocked bench running the length of the trench 2 km below the ocean’s surface; they eat on the sea-level coastline – the universally recognizable image of a world map – immersed in a sectional cut through the world. Beneath, ocean contours cascade; above, arrays of mountains rise up, peaking at the Himalayas at 2.1 metres. Striated with longitudinal lines, the table’s surfaces are perforated with patterns of global cities, illuminated by a local light source for each area.

Haw’s highly crafted, sensual design is reconfigurable and he envisages other possible world organizations enabling ‘radical cartographic mashups’. The carved modules can interlink or detach to pack flat, and because their complex geometries conform to the terrestrial grid, longitudinal slices can be swapped and recombined to create new map forms, or parts of the table can be pulled apart to create café seating.

Worldscape, Atmos, Stratford Town Hall, London, 2012. Photo: Mat Smith.

Reinventing the typical dinner party setting on trans-territorial lines – literally – Haw is less interested in merely the ergonomics of dining’s comforting physical and emotional function than experientially provoking encounters with space, place and their encounter with unfamiliar kinaesthetics.

Worldscape, Atmos, 2012. Photo: Jonathan Perugia.

Worldscape was launched at the start of the London Olympics July 2012 with Global Feast, a dining experience with a menu created by Kerstin Rodgers, founder of The Underground Restaurant staged on all 20 successive evenings of at the Old Town Hall in Stratford next to the action, shifting progressively further east through all the world’s cuisines. An homage to London’s ‘world within a world, rich multiplicity of its population and extensive home restaurant food scene’, it was conceived by Latitudinal Cuisine, a collective culinary project Haw set up in April 2009, involving collective weekly dinners large and small popping up at a myriad of venues in London and beyond for which guests cook food from the latitude corresponding to the day of the year. Ranging from the Telematic, Eat with Art, Edible Edifices, Flower Food and World Christmas Cuisine, Haw’s concept, like Worldscape, is a powerful way to collapse distance and bring people together.