4

Issue 4

4

Issue 4

Vefresh, the open innovation movement launched at the VEF Cultural Palace, Riga, 100 years after VEF, the legendary Latvian manufacturer of electrical and electronic products was founded in Riga, 6 June 2019.

Bursting the bubble: Riga reworks its urbanist legacy

Urban planning has relied on silo thinking and across time dealt with earlier crises and changes by making big picture shifts, and applying philanthropy, creative inventions and drastic social interventions. That pattern is not so dissimilar to today’s uncompromising top down planning. But today’s circumstances – positive and negative – often usher in a process of incremental radical reinvention of planning’s metabolic powers. Riga, Latvia’s capital, where 637,000 people live – 33% of the country’s population – is demonstrating a wealth of innovative strategic planning strategies. These are likely to burst the bubble of traditional planning’s inward-facing silo mentality – well past-its-sell-by date in ways of benefit right across society.

Latvia has been emptying out since it joined the EU on 1 May 2004, losing approximately 20% of its population to work in other EU member states, mostly young people with further education. Accessible public transport, cleanliness, access to education and cultural events, emerging creative quarters – especially in the lead up to Riga taking the mantle of European Capital of Culture in 2014, as well as a low crime rate, did not stop them leaving for better paid jobs, career opportunities and to broaden their experience.

The loss of active buildings and spaces even in the urban centre of Riga, the largest city in the Baltic, can’t have encouraged some; but for others it meant much more space for creative expression and community life, as I talk about my interview with Forbes magazine this summer, Cultural Renewal Drives Economic Regeneration in Riga, Latvia, and Will Mawhood, editor of Deep Baltic, the magazine for travel and culture in the Baltics, discusses in his perceptive 2016 essay, ‘The Capital of Empty Spaces: Dealing with the Shrinking of the Great Baltic City’.

While some planners may still pine to turn the clock back and fulfill the promise of the earlier boom years, ‘as a city, we are shrinking, so that means we must do smart thinking’ on all fronts, says Guntars Ruskuls, the Acting Head of Riga City Council’s Strategic Management Board when I meet him in his office in January 2019. Some of those working the hardest to change things for the better, never left, have returned, or keep a foot in two countries, in the modern way.

In the period of Latvia’s occupation by the Soviet Union after the Second World War the population was nearly 1 million. There was no metro back then, and a lack of planning. Then the Soviet Union collapsed, population figures nosedived to 640,000, yet Riga had an infrastructure designed for 1 million people which was not easy to maintain, especially after Latvia’s independence in 1991. The answer to the dilemma is incentives to stay including improving the environment for young people so they can return, or stay and enjoy an urban lifestyle that is more liveable.

Riga, Latvia. © Stijn Hüwels.

Riga Restaurant Festival 2017. © Karlis Dambrans.

There is strength in Riga’s ability to compete, but the economic city is monocentric and the wider regional cohesion is not so strong. 30,000 people live in the city centre, and the economic crisis brought in ‘a lot of empty windows’, a time preceded by a decentralised economic plan taking energy away from the city centre.

In 2013, as Riga was getting ready to host European Capital of Culture in 2014, the Occupy Me! sticker campaign was carried out by NGOs to promote the creative reuse of abandoned buildings, as part of the 2013 Survival Kit arts festival. This led to city-wide mapping of more than 350 empty buildings and a wider coalition being formed and a partnership between the municipality and an NGO, Free Riga, dedicated to temporary use, reviving disused buildings with a mix of open spaces for creative and social activities.

Tallinas Street Quarter Riga, Latvia © Free Riga.

Free Riga’s projects include 16 buildings reopened on Tallinas Street as a creative quarter with rooms for a wide range of activities and artists’ residences, and at 57 Kalēju Street in Old Riga, an apartment building from 1930, to host a bar, a museum and international creative residencies. Cofinanced by the occupants of the spaces, and following the successful opening of several properties besides Tallinas – Zunda Garden, D27 and Lastadija – Free Riga report that ‘the number of potential residents and stakeholders is growing, and it is expanding the team to launch new projects for the efficient use of empty buildings’.

Cooking up Resilient City Economies, URBACT Festival, Riga, 2015 © URBACT.jpg

The new local strategic planning ideas emerging today are about Riga as a community-friendly, compact city, with green corridors, more green areas in any developments to improve the air quality, a housing policy to try to keep people local. And mobility based on cycling and pedestrian quality of life in the Riga’s wide streets, many of which were built in the 19thcentury. Ruskuls says ‘it’s good we (the municipality) are not dealing with a polycentric model anymore’, but are instead revitalising recreational territories, and managing urban sprawl.

For the last 12 years the Council has been working with two or three NGOs, but now works with more than 20 of them on locally produced ideas and activism. The Board responsible for Riga’s sustainability strategy includes architects, geographers and a sociologist to strengthen the city’s 58 local neighbourhoods to make them more balanced. Now is a good time to support their social capital, Ruskuls and his colleague Justine Pantelejeva, a young strategic planner, feel, and they see the younger generation becoming increasingly active in trying to break the old planning rules by applying their skills in alternative, bottom up urbanism.

Riga smart city sustainable energy plan, 2014-20.

This social paradigm shift has an ecological imperative attached to it, and Riga is evolving as one of the world’s greener cities in terms of renewables, with biomass and district energy systems. Latvia shares scope for renewable energy resource building with the Baltics and their maritime territories more widely, and this new wave of industrial activities will be increasingly reflected in the make up of entrepreneurial activities in Riga’s technology clusters in the future. But the fabric of the city matters profoundly and must be navigated with skill: ‘we still feel this post-communist heritage’, says Pantejeva.

The historic city has developed by annexing different territories, artificially expanded‘, and all the ‘developers wanted to develop shopping malls’. Factories were also left in the middle of the city as it expanded. ‘Community used to be a strange word’, but now ‘we have a broader vision – diversity is the greatest value of Riga’, she says. ‘Social integration is happening in all those neighbourhoods (the 58 were defined by the munipality in 2007).

Open green landscaped spaces at VEF/Vefresh innovation district, Riga, Latvia. Spatial concept by Eter.

Much more than a mere cluster, the VEF innovation district and its surrounding territories close to the centre of Riga is a significant piece of the city taking shape in a former Soviet industrial and residential area. It has been billed as Riga’s Silicon Valley, and you can see the point, due to its build up of tech businesses, but, building on a rare cultural heritage and the deployment of diverse ideas in its strategic planning makes VEF – and its overarching Vefresh open innovation movement – much more of a unique indigenous model and phenomenon.

Before the Second World War, VEF (Valsts Elektrotehnikā Fabrika, or State Electrical Factory), the legendary manufacturing giant of the Minox miniature (‘spy’) camera invented by the German-Latvian Walter Zapp, a firm founded a century ago when Latvia began its first phase of independence, had their factory there but people haven’t lived in the area for a century, Viesturs Celmins, Chief Executive of Vefresh, told me. Celmins is one of the figures Pantelejeva had in mind when pointing out the proactive role of younger placemakers in the capital. Celmins is a social anthropologist who is managing to fit in the completion of his PhD at Cambridge University alongside his city-making role in Riga.

Jaunā Teika, Vefresh, Riga.

Jaunā Teika, Vefresh, Riga.

The developer Hanner is creator of the pilot mixed use district Jauna Teika on the northern part of the site. At Jauna Teika the playfully designed multi-level interior spaces of the first operational co-working building are full of people at work, and about 85% of them live locally – either as members of 600 families, or on their own – along with other employees in the district, just a walk away in new apartment blocks.

Open green landscaped spaces at VEF/Vefresh innovation district, Riga, Latvia. Spatial concept by Eter.

Open green landscaped spaces at VEF/Vefresh innovation district, Riga, Latvia. Spatial concept by Eter.

The liveable urbanism here, relying on good landscape architecture plans for the public areas and a wide range of community amenities, makes the liveable urbanism approach much better than at California’s Silicon Valley, where workers are shuttled in on National Express buses. Smart transport points and pedestrian crossings, bikes, park and picnic sites, playgrounds and outdoor public space are in the works for the site around VEF.

Vefresh – a name combining the words VEF and ‘refresh’ – is a joint venture between Latvian Mobile Telecom (LMT), ICT firm Accenture – the third largest employer in Latvia – developers New Hanza Capital, VEF Cultural Palace, a local cultural centre run by Riga’s municipality, and Jauna Teika (Hanner). It is an open innovation movement which will enables a pilot demonstrating how to improve the area, for mobility, public transport, education, drone technology and so on.

VEF/Vefresh innovation district, Riga, Latvia. Spatial concept by Eter.

The district is sliced by Riga’s main transport artery – Brivibas street, intersected by 15 different public transport routes, has an active cyclist flow and in a 5 minute walking distance is the Čiekurkalns train station, for which an intermodal transport hub plan is in the offing. Celmins also explains that the VEF district also has one of Latvia’s first operational 5G base stations ready for work, and land that can be used for testing mobility innovations requiring a less intensive traffic flow.

Viesturs Celmins, Chief Executive of Vefresh, at the launch of the open innovation movement, Riga, June 2019.

‘It’s a microcosm in which things can be checked and turned into products’, he announced at the launch of Vefresh’s open innovation movement in Riga on 6 June 2019, an official event for the signing of the Memorandum of Cooperation between the businesses involved, Riga municipalities’ and state representatives. Juris Bind, president of LMT, regarded the area as one with the right ‘aura’, where ‘people are prepared to go’ and the group invites other companies to participate in the movement. This concept lends credibility to the Vefresh brand, for which 85m euros in taxes and 43% of Latvia’s IT exports are at stake.

‘We are looking at inhabitants moving to the area to either rent or buy. Just five years ago (2014) there were very few and far between – as well as companies moving or opening their offices in the area’, explains Celmins, which he says means they are measuring impact to date by ‘head count, and the amount of companies present.

VEF is currently already a hotspot of ICT firms, in addition to Accenture, including MikroTik, one of the largest service providers of wireless technologies in the Baltic States, Tieto and LMT (which provides 5G connection to its neighbour Mikrotik as they are actively involved in testing it for the locality’s wireless infrastructure), employing a total of around 4,000 ICT professionals (summer 2019). Latvia is holding up well against its traditional IT competitor, Estonia, with in 2017 exports of ICT services from Latvia worth 779 million compared with Estonia’s 751 million export market. This gives government officials confidence that the district will keep growing, according to Guntis Rubins, Head of the Office of the Latvian Investment and Development Agency in the UK.

Totaldobže arts centre in the VEF district, hosting electro-acoustic music and sound installation.

At the moment the VEF district as a whole is predominantly a place for work. The earlier inspiring wave of cultural activities which took place at arts centres there, like the renowned Totaldobze, set up 2008 by artist Kaspars Lielgalvis in an old factory building in 2008, ended after rents were raised, and the revived industrial buildings reconstructed after VEF decided to make the area a creative industries hub. Totaldobze was one of those which stayed active; it moved to alternative premises to collaborate with a network of other cultural bodies and then to Liepāja, Latvia’s third largest city on the coast 200km away, but is hoping to return to Riga in the near future.

The imperative for the VEF in its latest plans to deliver an affordable high quality of life is strong, if it is going to create a genuine community legacy for the city. The current commercial make up of VEF is not solely limited corporations – Tieto, Siemens, DNB Nord Bank, but includes SMEs, including start-ups, too. Celmins says that ‘by this time next year (summer 2020) there should be 5500 ICT professionals working in the area’ (a year-on increase of 1,500 people), and ‘by 2021 there might be another 1,000 added with New Hanza Capital finishing up their renovation of the historic VEF quarter’, where Accenture and Mikrotik are based. ‘We plan to assess innovative capacities too’, adds Celmins, ‘by tracking how many startups are started here and how much progress is made among them’.

The launch of the Vefresh open innovation movement, Riga, 2019.

VEF is ‘encircled by railroad tracks and criss-crossed by one of the busiest streets in the city’, he explains, so ‘the main goal of mine for Vefresh (overall) is accessibility and (a) humanised environment for pedestrians, cyclists and people with disabilities. As long as we are able to ensure safe pedestrian crossing, introduce ‘green corridors’ and improve public transport infrastructure (which he reckons will take five years at least) – we are going to stay relevant’. How else will the scheme stay relevant as a poeple-friendly place? The second major area of intervention is to involve teachers and students at local secondary schools in learning about technology firsthand from the companies operating in the area.

This vision for local learning is especially geared towards IT and design subjects because ‘we have some of the lowest rates of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) applicants in the EU. Whether shadowing employees once a year (on site) or a designated ‘maker space’ for students or modern hackathon events for IT teachers from local schools, we will continue the work that Accenture has started with IT education at a local level’. Accenture, he explains, has created free online/video courses for primary and secondary school students in Latvia, and are embarking on running courses for teachers in autumn 2019.

In their gameplan Celmins and his colleagues have been careful to foreground cultural regeneration of the whole area through the making of ‘third spaces’, the term American sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined in 1991 (see his book Celebrating the Third Space, 2000, to refer to ‘regular, voluntary and informal’ spaces where people will go and spend their time between home (‘first’ space) and work (‘second’ space) to interact and exchange ideas, build their relationships and have a good time. Breaking the shuttle between home and work, they help to strengthen the community’s social vitality, and are environments Oldenburg hopes would genuinely promote social equity, and represent ‘the grassroots of democracy’.

Vefresh’s cultural policy ‘addresses the fact that there are hardly any services available for inhabitants and employees in the area on this side of the railway ring road’. So to invigorate the emerging neighbourhood during the summer seasons partners have hosted street food/culinary festivals where various cafes and restaurants have been invited to present their signature dishes and drinks to the wider public at more affordable prices than usual. Many of these events have included musicians, DJs and performers as well as provided events for children, depending on their theme.

VEF/Vefresh innovation district, Riga, Latvia. Spatial concept by Eter.

On 4 May 2018 – as part of the country-wide 100-year celebration of Latvian independence – Vefresh was able to get the municipality to agree to close down street intersections to all traffic in order to host a large, day long festival for the local community of inhabitants and employees. Workshops, talks and lectures hosted by companies along with sports activities and a large stage with performers in the evening underlined the exciting cultural transformation of the area. These events need to be not only short-lived ‘meanwhile uses’, but enable local people to test out new business ideas, as well as maintain their value as a social catalyst.

How is Celmins making sure the creative decision-making for Vefresh is genuinely participatory? ‘We are trying to involve our community and employees via polls and hands-on workshops, where people are invited to suggest interventions they would like to see in the area. ‘Whether we are able to pull these off at the state or municipal level remains to be seen’, he admits. ‘I believe this bottom-up approach is almost universal now, yet it does not guarantee results overnight’, he cautions, and tells me that ‘tenants at JT are not required or asked to pay towards infrastructure, improvements or cultural programming in the area’.

He’s also realistic about the speed at which contemporary homes can be built to cater for more Latvians returning home to Riga and an expanding base of international workers. Across the wider city, most inhabitants live in housing blocks, some from Soviet times when mass housing was built in Riga through the industrialisation programme. ‘I don’t believe that there will be any drastic changes to this any time soon, as it is simply impossible to create alternative housing options at a quick pace’.

Moreover, ‘there is a very strong and ongoing trend for people to move away from the city to the suburbs and commute back to the city’ once their pay rises. So ‘at Vefresh – and perhaps, the city at large – we are working at several levels at once. How do we make urban living appealing by nurturing a vision of having a flat or house in the city, rather than in the suburbs?’. Secondly, ‘how do we create the best possible quality of life (for people from) various walks of life, not just limited to ICT professionals, who tend to have a decent income anyway’.

Jauna Teika has just opened a second co-working building called Teikums 2 to accommodate the increase in demand. Celmins says more co-working spaces are opening up around Riga. Is there enough of a market for them? ‘How sustainable this model of the gig-economy is – which fuels co-working – remains to be seen. But I believe we are not going back to conventional 9-5 and cubicles either’, he adds.

What role is the public sector playing in this significant project? ‘Since most of the infrastructure, including transport, is owned and run by the city municipality and the Latvian state, it is inevitable that we have to work with public partners’, says Celmins. Currently the team is testing out a ‘micro mobility’ point in the VEF quarter, which will include bike, car and scooter rentals, charging stations for e-mobility as well as bike stands, and, possibly, a navigation map for real time assessment that should help people to choose the best option for public transport among many.

‘If this prototype – tested out by our own employees, inhabitants and guests alike – turns out successfully, these station points will be replicated and adapted for other parts of the city as well’, he says. ‘We plan to readjust the transport stops, too, and align them with transport schedules as well as ‘last mile’ solutions and integrate the railroad into the city fabric, but this is more like a 5 year plan rather than current reality’.

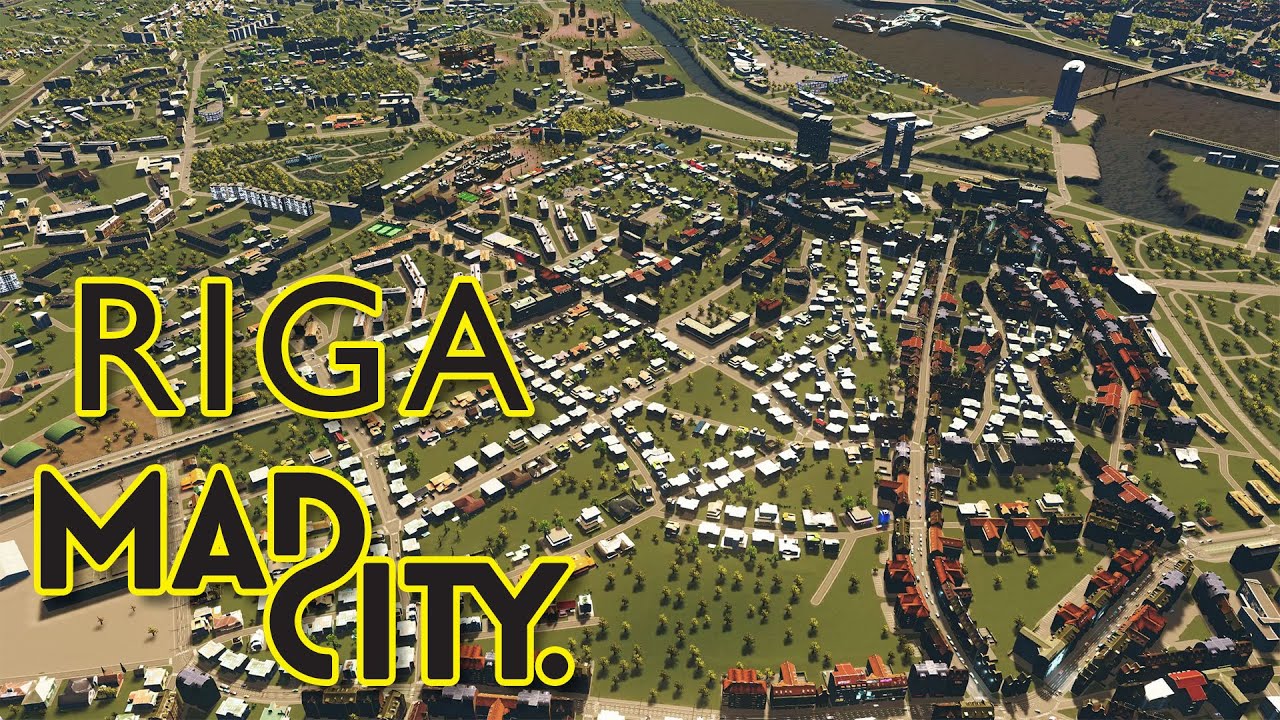

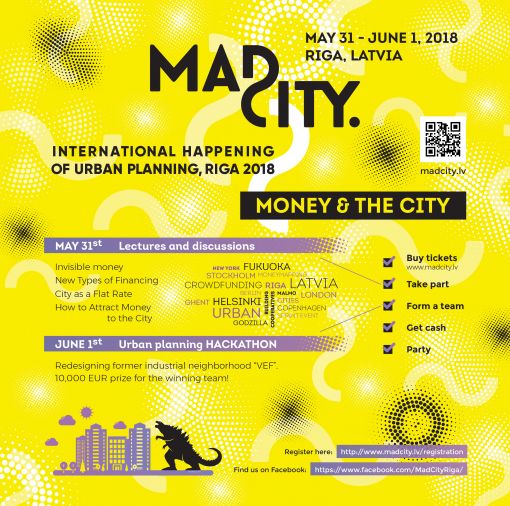

So if strategic planning in Riga is shifting towards embracing some more bottom-up tendencies, what newer mechanisms enable city residents to play an active role? Celmins was one of the speakers in May 2019 at the latest MadCity ‘international happening of urban planning’ was staged, a two-day long event founded three years ago by urban designer Neils Balgalis. He calls it a ‘sparkling and favourful event for urban developers, bankers, bikers, artists and IT guys’. The biggest number of participants – 350 – came to Mad City this year, from 15 different countries came this year: urban planning experts and practitioners, city officials, politicians, business people, tech specialists, NGO representatives and local inhabitants.

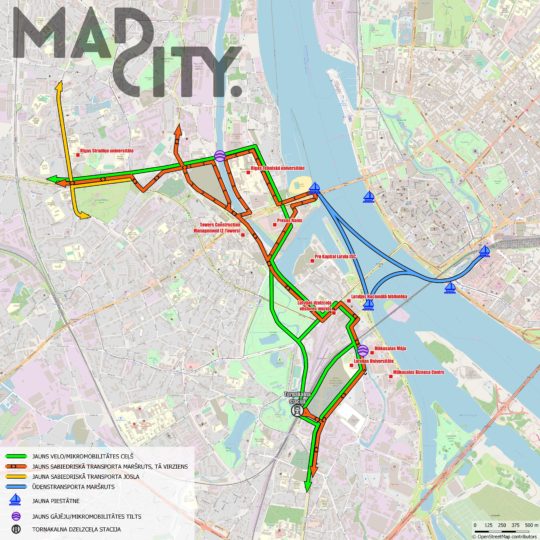

The Mad City hackathon route, Riga Knowledge Mile, left bank of Riga, Latvia, May 2019. © Mad City.

Planning-related people represented more than 75% of the participants at this year’s Mad City. ‘Participants discussed the concept of micromobility for Riga, not as some distant dream but as a realistic aim and a thing to work on’, explains Balgalis. The subject was the Pardaugava area on the left bank of Riga. Home to Latvia’s leading universities, the National Library and the Railway History Museum and several office complexes, and on the other side of the city from Vefresh, it is gradually gaining recognition in Latvia and around the world as the ‘Riga Knowledge Mile’ (RKM).

‘The Knowledge Mile is a place where ideas are made, where the entrepreneur meets science, the student meets their employer, science meets reality and ideas are made into products’, he explains. ‘Experience show that ease of everyday movement and encounter is a major contributor to innovation’. Over 700 million euros will be invested over the next seven years here, building on 800 million euros through public and private sector investments over the last five years. Consequently n order to make full use of Riga’s potential for innovation, he maintains, which results from ‘this concentration of universities and businesses, an efficient mobility infrastructure combining rail, public transport, road transport, pedestrians, cyclists, electric scooters, boats and so on, are needed’.

Mad City 2019, Riga, Latvia.

The public transport backbone will be a railway station built on the Rail Baltic line allowing people to reach Riga International Airport easy, and provide rail connections to the rest of Latvia is its public transport backbone. Anticipating 40,000 students and more than 20,000 people working at the Knowledge Mile, Balgalis is keen to explore how this boost in public transport accessibility can best coexist with an expansion in micromobility, shared mobility services and infrastructure, mobility as-a-service as well as urban connections by water via the River Daugava.

Mad City is a catalyst for faster development of ideas and places. It brought together ten international teams including representatives of all the Knowledge Mile stakeholder bodies, as well as local people from two different neighbourhoods and urban planning experts. Both students and teachers from five different universities were among those working on the ambition to help to shape solutions for the Knowledge Mile as an emerging cultural place, a ‘collaboration creator, new idea generator and opportunity revealer’, Balgalis explains. Mad City’s creative programming and format – ‘basically, it’s a game anyone can register for, irrespective of their job or walk of life – rose to the occasion over two long days, ending with a big group hug before the block party on the final evening.

How can innovation districts like Vefresh and the left bank in Riga, and others internationally, locate, create and distribute their knowledge, Balgalis wanted to know? What are the ‘relationships between infrastructures, networks and the city’s systems and what are their impacts on social structures?’. The biggest challenge for the Knowledge Mile ‘will be cooperation among the universities and attracting companies to Pardaugava – there are few businesses in the area right now’, one that is close to the city centre but not easily accessible, feels Celmins, who shared ideas on day one on the challenges and potentials of the area to absorb the ‘Knowledge Mile’ as well as the future Rail Baltic infrastructure being planned for Riga.

On top of the challenge of drawing businesses to set up at the Knowledge Mile, another pressing issue is to create a decent rental housing and public service infrastructure for local and foreign students which would include bike lanes, bike stands, pedestrian walkways and diversified, active public spaces with cafes, bars and cultural institutions’. At the moment, he says, ‘the area is rather busy during the day, but becomes rather deserted during the night, similar to (the) realities at Vefresh’.

Mad City is clearly of high value as a genuinely public meeting about visions for future quality of life of districts like these, as well as a lot of fun. The hackathon – a challenging, sprint-like design event compressed into 24 hours in order to creatively solve a problem on day two, is preceded by lectures, discussions and speed dating so people can get to know each other and form groups the day before. Local players with an interest in the Daugava left bank, including the three universities, developers and other companies, came together to form the hackathon teams.

Participants in the hackathon at Mad City, May 2019, trundle shopping trolleys along a testing terrain to their designated hackathon workspace in the Riga Knowledge Mile, Mad City, 2019, Riga, Latvia.

The players were given three specific tasks: within six hours, come up with ‘realistic solutions’ – programming, design, IT and funding ideas – for better connections for pedestrians, cyclists and micro-mobility solutions in the Knowledge Mile; the programming of regular ferry connections across the Daugava River in the city; and developing the concept, ’20 minutes from any office, apartment or auditorium to the airport. They focused on formulating specific actions (including assessing the existing interconnectivity of the RKM spaces), projects and recommendations to improve the urban environment the Knowledge Mile as it comes into being over the next decade.

Mad City hackathon participants convey their thoughts from boats on the Daugava River in Riga, Latvia, May 2019.

Taking part in Mad City is an immersive experience. Firstly, participants they were taken to the event venue by boat over the Daugava River, given the opportunity to try out electric scooters on arrival, and trundle shopping trolleys along a testing terrain to their designated hackathon workspace. This intense hacking culminated in all the newborn ideas and the process being published on the respective team’s Instagram account, eliciting questions across social media.

Mad City 2019, Riga, Latvia.

Speakers were hoisted up and down to the stage in construction lifts to give their ‘sales pitch’.at the three-way idea play-off between shortlisted teams on the floating venue, NOASS, watched by all participants present and online viewers, all of whom get to vote on the winners. An international jury, stakeholders, participants and online audience (taking part in the vote) got to decide on the distribution of the Mad City prize money pot. A swift awards ceremony followed before the event segued into convivial block party mode.

Mad City 2019, Riga, Latvia.

How does Balgalis ensure that the proposals for strengthening the RKM has conjured up at Mad City 2019 don’t lie on shelves after the party is over? Straight away they summarise the vision and proposals for immediate, ‘quick win’ smaller scale improvements over the first two years. Estimated at a cost of 2.5 milion euros, these will ‘provide a good basis for mutual cooperation between (the) universities, businesses, Riga municipality and public authorities. He underlines that the proposals ‘reflect the common interest of all partners in the development of the area’.

To improve public transport, a new NW-SE route needs to be created, to connect the Knowledge Mile, and public transport lanes on Dzirciema Street, as well as on the Vansu and Akmens Bridge, and guarantee a high priority for public transport in the future. This goes hand-in-hand with improving access to the existing Tornakalns railway station through fast and efficient connections and more active use of passenger trains.

Constructing pedestrian bridges across the Klivleina Ditch and the Zunda Canal 9at the end of Durbes Street) enables comfortable walking and cycling routes between universities, businesses and the Tornakalns rail station. Creating a fully-fledged micromobility connection brings about easy movement between all stakeholders in the NW-SE area. A public dock for small watercraft on the right bank of the Daugava River at the 11thNovembra Embankment, National Library and Vansu Bridge helps activate the area for water transport.

Mad City is an immersive experience, Riga, Latvia, May 2019.

‘Mad City is an urban planning competition that welcomes everyone’s participation because it is simultaneously a motivation-driven game, a collaboration creator and a learning process’, says Balgalis. Mad City 2019’s attendance figures also make it now the ‘biggest urban planning party in the Baltics, he adds. Just three years it too short a life for Mad City to have a profound impact, he feels, but already ‘we see some things happening’.

He sees in Riga a ‘shift in planning and city development mentality, away from a few megaprojects to many small activities’ – ‘soft’, community events and activities. Greater emphasis is also being placed on intensifying Riga’s urban core as opposed to creating new development territories. And the planning community has come to accept sustainable and smart mobility concepts, and the need to prioritise public transport and shared micromobility over private cars.

Mad City’s verve in busting out of tired old planning as a dull and exclusive discipline tied up in silo thinking, to embrace the wider public, has ignited the admiration of the design professions. A month after the 2019 event Mad City won a ‘Silver Pineapple’ award for Processes at the Latvian Architecture Award of 2019. ‘Ideas can be more influential than buildings, so it is important to have a platform to spread ideas. Today’s cities have modern problems, and this event proves that speaking, discussing and acting are still the most effective way to destroy the bubble in which society lives’, the jury citation explained.

Celmins agrees that Mad City is ‘a great addition to the planning landscape of Riga’. For him the event ‘fills a discursive gap in urban planning and allows the local community to meet and hear some good speakers from abroad’. He also appreciates the hackathon with its ‘activists, planners and inhabitants working side by side’, pointing out that this year’s event also gave the local community the benefit of satellite events engaging a major discussion about the whereabouts of Riga’s new concert hall.

‘Mad’ in the event’s title refers to the way city life is often imagined, but Celmins prefers the intensely interactive and performative ‘mad’ side of the event. He acknowledges that it can appear to some ‘as if urban planners are merely venting once a year, and as such some of the matters discussed can be seen as sensationalist or fringe, which, most of the time, they aren’t at all. Mad City has both micro- and macro-level urban discussions on the bill, so you could be hearing about or discussing scooters as ‘last mile’ solutions, and then switch focus to a talk on the future of the city.

This kind of swift step change in focus often comes with the territory at urbanism events globally. Packed with ideas, soundbites and golden networking opportunities they mostly are. But the gratifying difference with Mad City is that you step away from conference halls into the city itself with ample opportunity to burn up a lot more energy keeping up with Balgalis’s interactive, multi-location programming.

Celmins feels that, irrespective of which part of Riga as a city you focus on today, in preparing for its future as a liveable, desirable city, ‘we need to focus on creating rich public infrastructures, including parks, squares, pedestrian street level activation and decent affordable housing opportunities, so that people would be excited to reconsider the city for living, not just working, consuming or transit’.

Mad City 2018, tackled a basic issue: Money and the City.

As the largest city in the Baltic States by population at more than 1 million residents it is hard to evaluate Riga’s future without considering the impact of Rail Baltica, the massive greenfield rail infrastructure project starting construction in 2020/21, that will create a total length of 870km of new tracks across the Baltics. It will enable Riga city centre to be upgraded, and make a Riga airport city possible, as well as having a transformative effect on the States’ secondary cities.

Rail Baltica also aims to improve the integration of the States into the EU, connecting a ‘missing link’ and delivering a new industrial and economic ecosystem and artery for trade. Kaspars Briskens at Rail Baltica sees it as a symbolic return of the States to Europe. Without Rail Baltica’s unification of north and south, there is a heavy reliance on east-west freight flow across the States, and very limited passenger movement between them, hence its national and regional priority. It will be funded equally by the three, with up to 85% by the EU, founded on the basis of shared infrastructure as a way to do away with nationalisms.

Rail Baltica will be fully electrified to avoid emissions, and the line will not interfere with the Natura 2000 protected and other environmentally sensitive protected locations. Hopes are pinned on its role as a powerful catalyst for sustainable economic growth, enabling a new corridor and transnational regional integration, evidenced by the success of the Oresund fixed link infrastructure between Sweden and Denmark.

How the Rail Baltica infrastructure will be incorporated into the existing city fabric – crossings, trains and stops and its implications Celmins flagged up as part of his Mad City talk. It’s no surprise to hear that Balgalis has chosen for the May 2020 Mad City event to continue the thread of this theme, Riga railway station and the city – ‘the change brought to the central station’s surrounding area by the Rail Baltica project and opportunities to create humane urban environments of the 21stcentury’.

With Mad City Balgalis is tapping into a growing community appetite and ‘madness’ for change and bubble-bursting. But keeping it real, and mad in the best sense of interactive and passionate Celmins also appreciates. Mad in the making, and mad for the prospect that Riga’s future city interventions are actually made by everyone.