4

Issue 4

4

Issue 4

Dujardin Mews, Enfield, completed 2017. Client: Enfield Council. Architects: Karakusevic Carson Architects with Maccreanor Lavington Architects. Landscape Design: East. © Mark Hadden.

Making things happen on the ground: interview with Paul Karakusevic, KCA

Addressing housing needs as a democratic principle through coherent and equitable urban plans and community engagement is a prerequisite for good city making and the advancement of genuinely liveable urbanism, argues architect Paul Karakusevic, founder of Karakusevic Carson Architects, in a new interview with Lucy Bullivant.

Lucy Bullivant (LB): KCA is responsible for award-winning public housing schemes including Dujardin Mews for Enfield Council, the Bacton Estate for Camden Council and King’s Crescent Phases 1 and 2 for Hackney Council, and some of London’s most significant council-led masterplans including Meridian Water (Enfield) and King’s Crescent (Hackney). In order to achieve an affordable housing supply of high quality, RIBA, as we know, argues for measures such as deploying CPO (Compulsory Purchase Orders), Development Corporation powers, lifting the borrowing cap for local authorities (which UK Prime Minister Theresa May finally announced the government would do at the Tory party conference in Sept 2018), resourcing the planning system and investing directly in social housing.

Paul, which of these do you regard as the most important and achievable within the next couple of years, as a way of alleviating the housing crisis? What are the pros and cons of each one?

Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council. @ Tim Crocker.

Paul Karakusevic (PK), Karakusevic Carson Architects: Lifting the borrowing cap can happen immediately and it is great news that this is finally in motion. We have been advocating it for many years. On the plus side it means much needed financial liquidity for councils, which means more projects of scale can be delivered. On the other hand, however, it means councils taking on more debt, which many will not rush to embrace, especially those with low performing housing revenue accounts. Also, given the precarious state of local government finance across services, the banking sector may view substantial increases as a potential credit risk in some areas of the UK. So higher borrowing levels will not solve the problem of affordable housing on its own.

Compulsory Purchase Orders (CPO) powers exist and are being used, but the process can be troublesome. When it works, CPO enables effective land assembly, which means getting more out of a development and ensuring obstacles to more capacity, integration and local links are removed. But it can be legally costly and time-consuming to pursue, so not without risks and potentially divisive. As democratically accountable bodies, councils have to tread carefully on this to avoid clumsy and slow moving processes that could take years to resolve and hold up delivery.

Paul Karakusevic, founder, Karakusevic Carson Architects, speaking at the Future Homes for London: Alternate Models conference, Royal College of Art, 2018.

I think councils embracing development corporation powers is potentially the most important for housing. But what we should really be doing is simply giving our local authorities the powers they need to act for the common good, especially at a large urban scale. Local government should act to ensure a mix and type of housing where it is needed rather than where it is easiest. This should be a fundamental principle of an urban democracy.

King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council. © Jim Stephenson, 2018.

However, any proposed legislative planning change will only be effective if local authorities have resources at their disposal to make things happen. Preparing land, drafting development parameters and parcelling land for a variety of developer types needs proper funding and well managed design and procurement processes from the start. Councils can also take on the risk of multi-tenure development including council, shared ownership, market rent and for sale.

LB: When you say that public housing should be treated as city infrastructure (your talk at the recent V&A event, Ten Futures for Social Housing, 20 Sept 2018), does this mean treating housing as an integral part of the tasks of properly structuring a whole neighbourhood, and prioritising discussions about the civic nature of how we dwell and mixed-use inhabitation (proximity of homes, work and community amenities),responding to changing lifestyles and needs and perceptions of public/private thresholds, and how they are reflected in those structural processes?

Exploded axonometric of block, King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council.

King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council. © Jim Stephenson, 2018.

PK: Imagine housing in the way that we see Crossrail 2 in London progressing. Here we have public money being lined up for a project of real ambition and scale that will be delivered because it is in the national interest to do so and the incredible economic benefits of doing so. Imagine instead that the transport secretary announced plans for a new urban railway with faster trains with more capacity, without a commitment to building track or buying any trains. That’s what the government has done for the past 15 years with housing. Announcing targets without delivering the real finance or developing a coherent plan for where it will be or what it will look like.

We have planning frameworks that promote almost everything: greenfield, brownfield, garden cities, eco-towns, the greenbelt, not the greenbelt, modular, traditional, beautiful, modern. It’s baffling to me. We need a robust plan for housing. One that is ambitious and intentional. It’s simply not enough to raise targets, miss them and raise them again to demonstrate how tough you are. This is pure politics, not planning.

Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council © Mark Hadden.

A city cannot function without infrastructure. We all understand this. We need sewers, drains, transport and schools, but what about where the people that work on these live? That is why housing needs to be treated as an integral part of urban infrastructure. Successful cities need thriving populations. To thrive, people need affordable and secure housing.

Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council. © Emanuelis Stasaitis.

LB: Do you agree with the Centre for Cities (Anthony Breach, Analyst, Centre for Cities blog post, 6 Oct 2018) that lifting the borrowing cap won’t address the biggest issues cities face, and that the key problem is a shortage of land in the planning system that can be developed? If so, what are the answers?

PK: I agree raising the borrowing cap will not be the solution to everything, but it will be a huge help. If we are to match the numbers and standards of developed countries like France – similar in size and wealth – cities like London need strong and well resourced local government. We have billions of public money committed to private sector projects like Help to Buy. If we scrapped this and instead spread it across devolved government in the UK our cities would reap a development bonanza. They could deliver transport projects themselves, they could purchase land, they could prepare brownfield and prepare masterplans and release it onto the market with progressive criteria.

There is no shortage of land in London or the UK, only a surplus of people repeating a market version of the city. Developers have told us they are not interested in tough sites and that they are expensive or unviable. It is the role of government to turn that around and to step in. Make it viable, create a market and if they are still not interested, do it yourself or find people who want to via co-housing groups and smaller developers.

Dujardin Mews by Karakusevic Carson Architects, Maccreanor Lavington. Client: Enfield Council. © Jim Stephenson.

LB: ‘The future success of social housing requires multiple agencies and a diversity of suppliers acting in tandem’, you write in your book Social Housing: Definitions and Design Exemplars (Paul Karakusevic and Abigail Batchelor, RIBA Publishing, 2017). What is the potential of local authorities ‘doing it by themselves, for themselves’, as you have described it in your public talks, as well as Community Land Trust (CLT) models such as Camley Street in King’s Cross, London, to achieve this higher level of creative shared responsibility that you call for?

PK: The potential is huge, but it needs to be unlocked and resourced. Countries across Europe have a strong tradition of direct action in the market to shape development and get the outcomes they want in order to create the cities they need. Vienna, for example, enables and pre-develops land and then parcels it up for market delivery, but instead of handing sites to those able to put in the highest financial offer, they invite bids and design submissions in response to four pillars of good development encompassing social purpose, levels of affordable housing, design quality and economic viability. This process supports a range of developer types which include community and resident-led approaches. Like many alternative models, CLTs need enabling. Under the current government there are billions in market enabling funds such as Help to Buy. If we could redirect that money into alternatives and de-risk the process local authorities would be able to explore it further.

Nightingale 1 housing, inspired by the principles of the Baugruppen movement in Germany, Melbourne, Breathe Architecture. Client: Nightingale, 2014.

LB: What were the most striking takeaway points for you about the progress of the emerging CLT movement in the country from the debates and presentations at the RCA’s Future Homes for London: Alternate Models (organised by the RCA City Design with St Ann’s Redevelopment Trust (StART) Haringey, The Architecture Foundation and Baylight Foundation) event in April 2018?

PK: Seeing the Swiss and German co-housing groups Mehr Als Wohnen, ifau and Zanderroth Architekten producing beautiful, generous and robust low cost housing and Jeremy Macleod’s incredible Nightingale model, a collaborative movement for sustainable, affordable housing in the city of Melbourne, Australia.

LB: Your book Social Housing: Definitions & Design is an inspirational call to action to create positive change in the delivery of public house through innovation and ambition shared across sectors. In broadening the range of routes to housing delivery, what are the main possible pitfalls and past mistakes the local authorities and Community Land Trusts need to be aware of in order to avoid?

Aneurin (‘Nye’) Bevan (1897-1960), Welsh Labour Party politician, Minister of Health, UK, 1945-51.

PK: If you take a look at the long history of public housing building in the UK, one of the reoccurring themes is the decline of quality and standards in pursuit of numbers and savings. Numbers and efficiencies which have usually been promised by over-excited and opportunistic politicians. We saw that in the interwar years with cottage and tenement estates, we saw it in the 1960s with building systems and we saw it with cuts to public housing in the 1980s. In all cases the result was substandard housing that the next generation had to pick up the bill for. In 1951, the then Labour minister for housing Nye Bevan famously said,‘We shall be judged for a year or two by the number of houses we build, we shall be judged in 10 years’ time by the type and quality of houses we build.’

Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council. @ Tim Crocker.

This is as applicable now as it was then. So the mistake was to over promise and to capitulate to profit centred contractors. Councils need to be ambitious and fight for quality, politicians need to be honest with people. Architects and planners need to design timeless and high quality housing and stick to their principles rather than operating in the interest of low grade developers and builders.

LB: As part of the reform and rebalancing of housing provision you discuss in your essay in the book, what desirable processes are needed to ensure all estate regeneration projects work well for all residents, including the making of a residents’ charter, and in what ways should they be applied?

PK: The process of redeveloping an estate is complex and no matter the scale of intervention it is going to impact on people’s lives. It is essential therefore that councils are up front and honest about the scale of works and why it’s happening. Most people are simply unaware of the dynamics of housing politics, planning and finance. I think it’s crucial that redevelopment programmes talk to residents as early as possible and develop strategies that accommodate local need and aspiration. A Residents Charter is important, it can ensure communication and project protocols are adhered to, but it is only as effective if the council is willing to follow the charter in the long term. As architects we ensure that our communication is straightforward. Plain English and honesty goes along way and so do legible drawings and clear models.

Bacton Estate Phase 1, Karakusevic Carson Architects, @ Tim Crocker.

Bacton Estate Phase 1, Karakusevic Carson Architects, @ Tim Crocker.

Site plan, masterplan, Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council.

LB: What breakthroughs has KCA successfully achieved through early discussions and straightforward communication in improving local quality of life, enabling residents to get the best out of public space, in its estate regeneration projects, for example, the Bacton Estate in Camden?

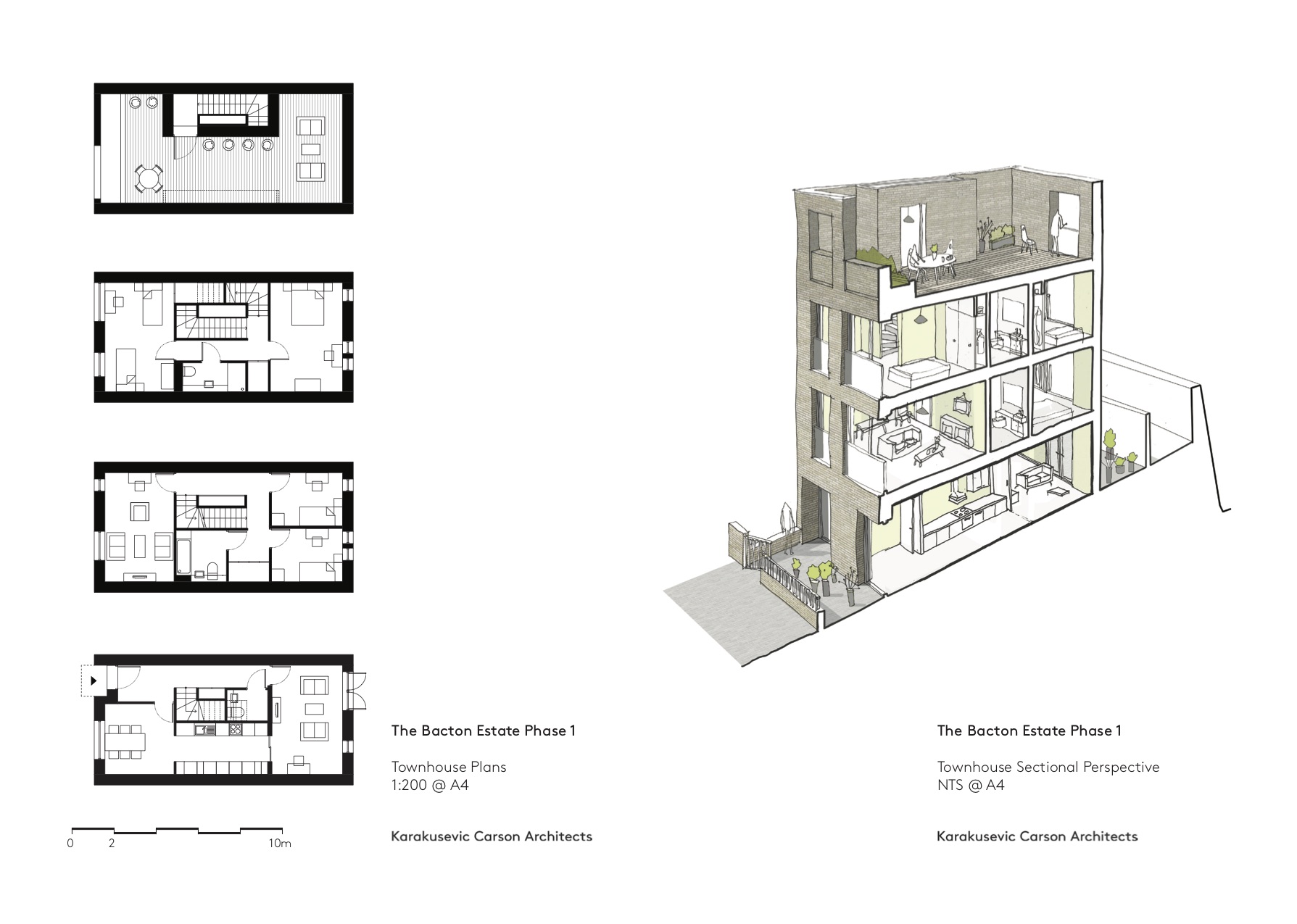

Unit plan and section perspective, Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council.

Location plan, Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council.

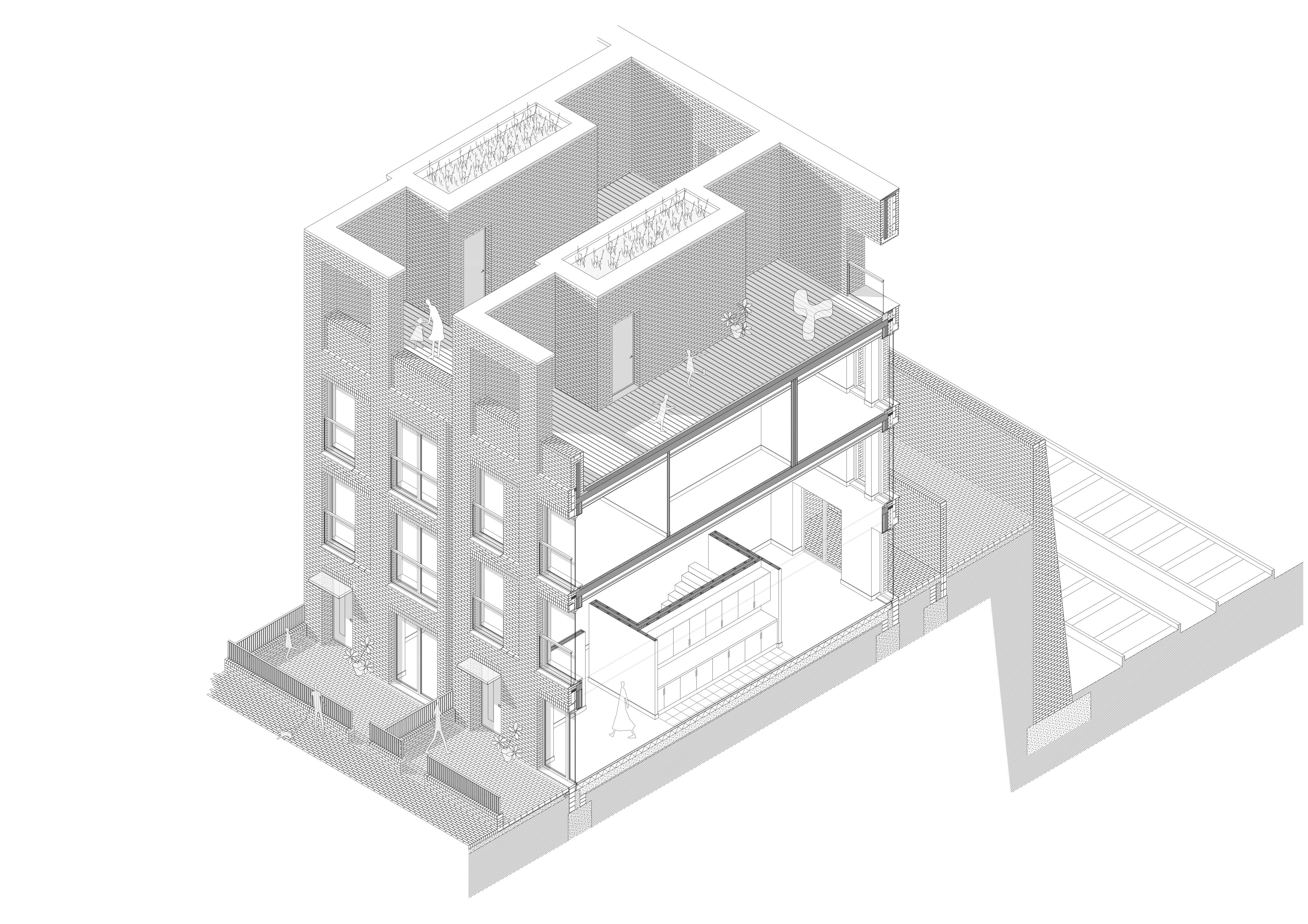

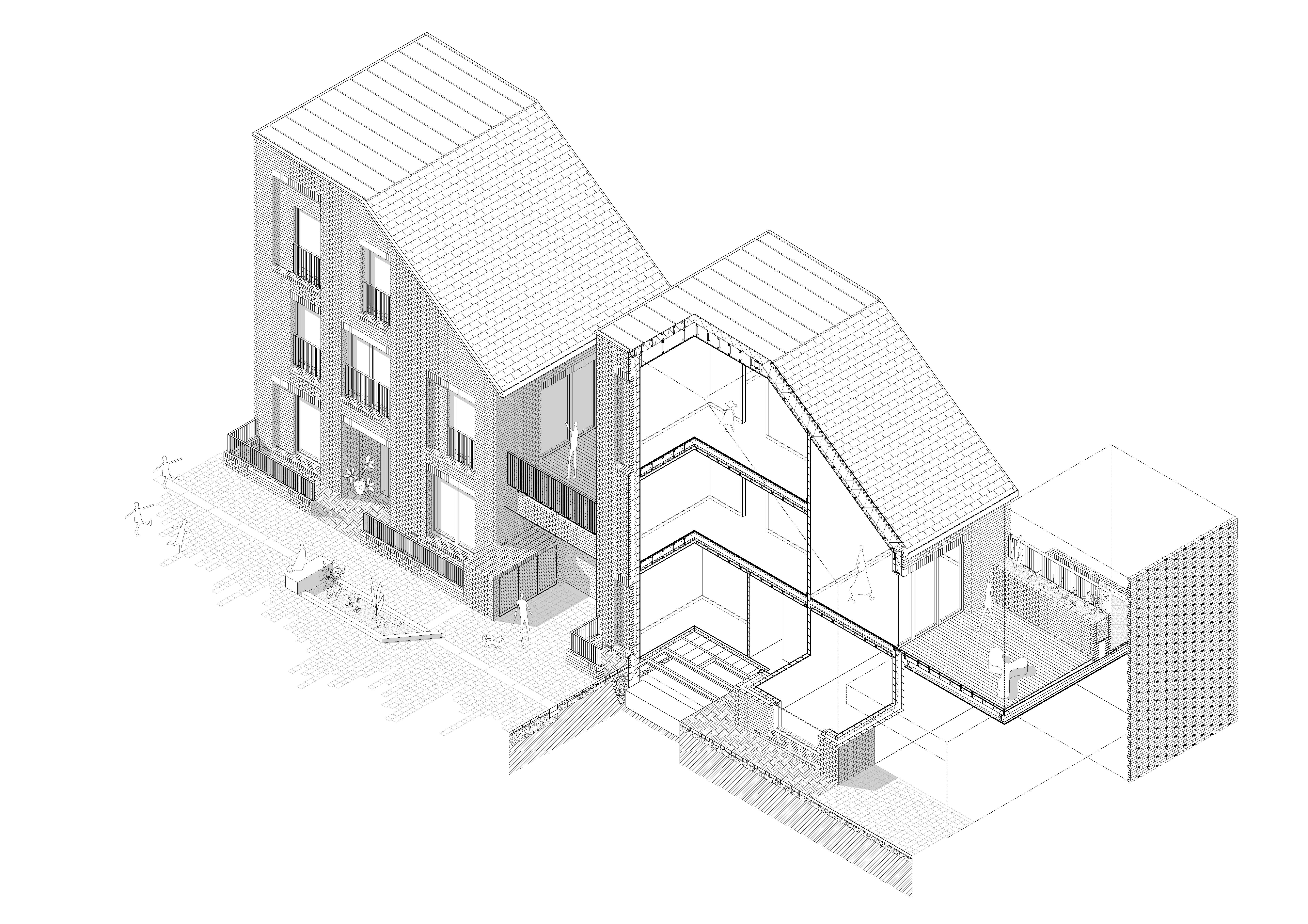

Axonometric, townhouse, Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council.

Site plan, Bacton Estate Phase 1, Gospel Oak, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Camden Council.

At Bacton we were working with residents who had firm ideas about what new homes should look and feel like. For years they had grown up with a functionalist and worn out utilitarian estate and so many were keen on embracing traditional domestic features and layout. However, they also understood that the typologies they had in mind would struggle to work on the site and achieve the same densities that would make the scheme viable. Therefore the challenge was to develop designs which could balance the expectations of home, domestic scale and character, while also getting the numbers on site. We worked closely with residents on this brief and through large scale models and sets of big and clear drawings could demonstrate that the numbers on the site could be achieved, while maintaining a strong and characterful domestic scale.

Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council. © Jim Stephenson.

LB: And how did you effectively test new dwelling types with the residents of the Alma Estate in Ponders End, Enfield, who moved into replacement homes at Dujardin Mews, KCA and Macreanor Lavington’s scheme of 38 residential units for Enfield Council?

Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council. © Tim Crocker.

PK: The site requirements at Dujardin Mews led us towards a robust street-based solution and it was one that the residents embraced immediately. The narrow site meant we needed to create hard working typologies incorporating a variety of home types and sizes, while the need for car parking necessitated the use of the street as both function and social amenity. So it was a happy marriage of things. We used big 1:25 models so that residents could see inside unit types and get to grips with the proposition. They were excited by the prospect of living next to their friends on a new street and the new types of spaces we could create around it.

Ground Floor Plan 1. 750, Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council.

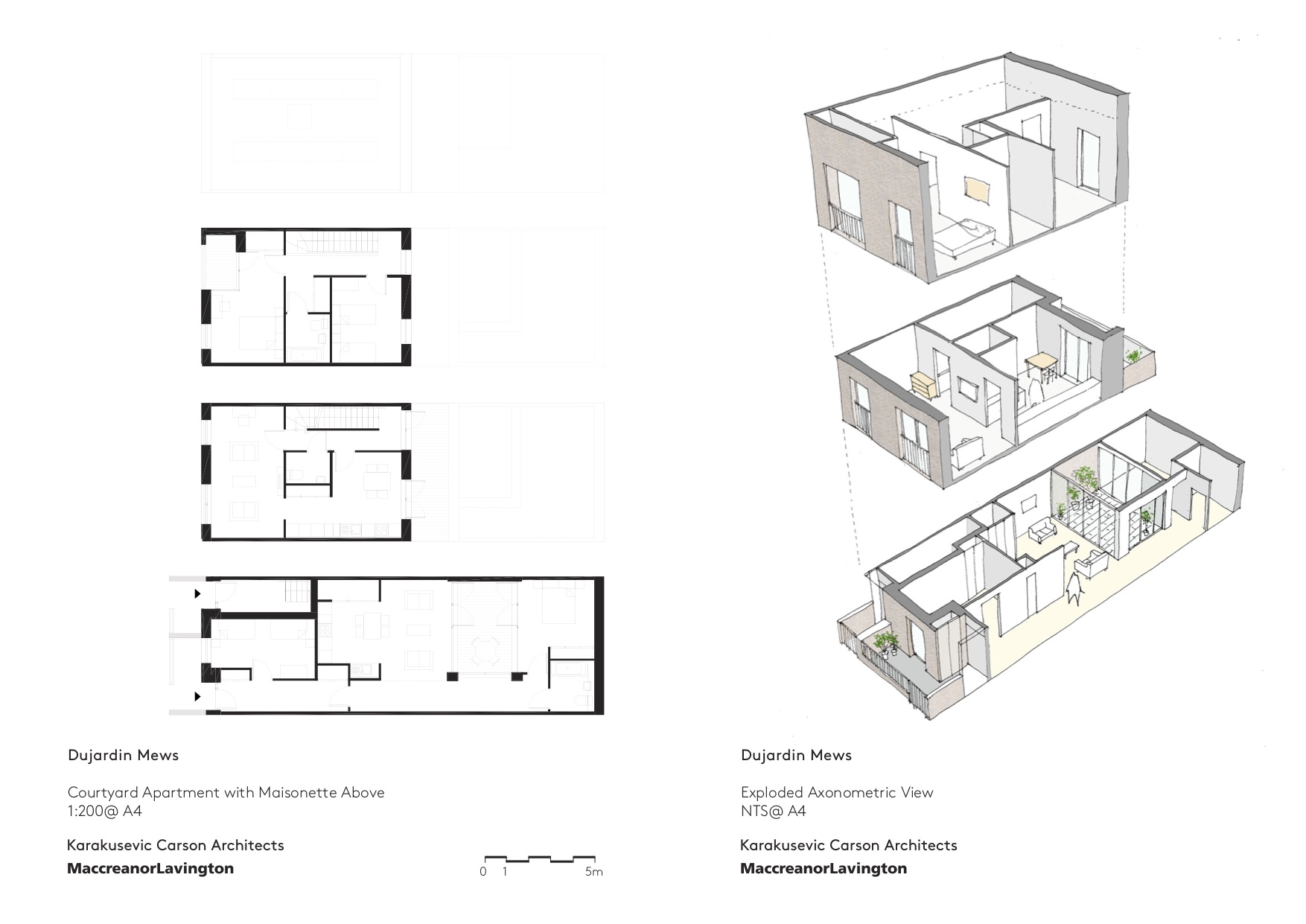

Bed Townhouse plans and axo, Courtyard Apartment plans and axo, Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council.

Courtyard Apartment plans and axo, Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council.

Sectional axonometric, Dujardin Mews, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Enfield Council.

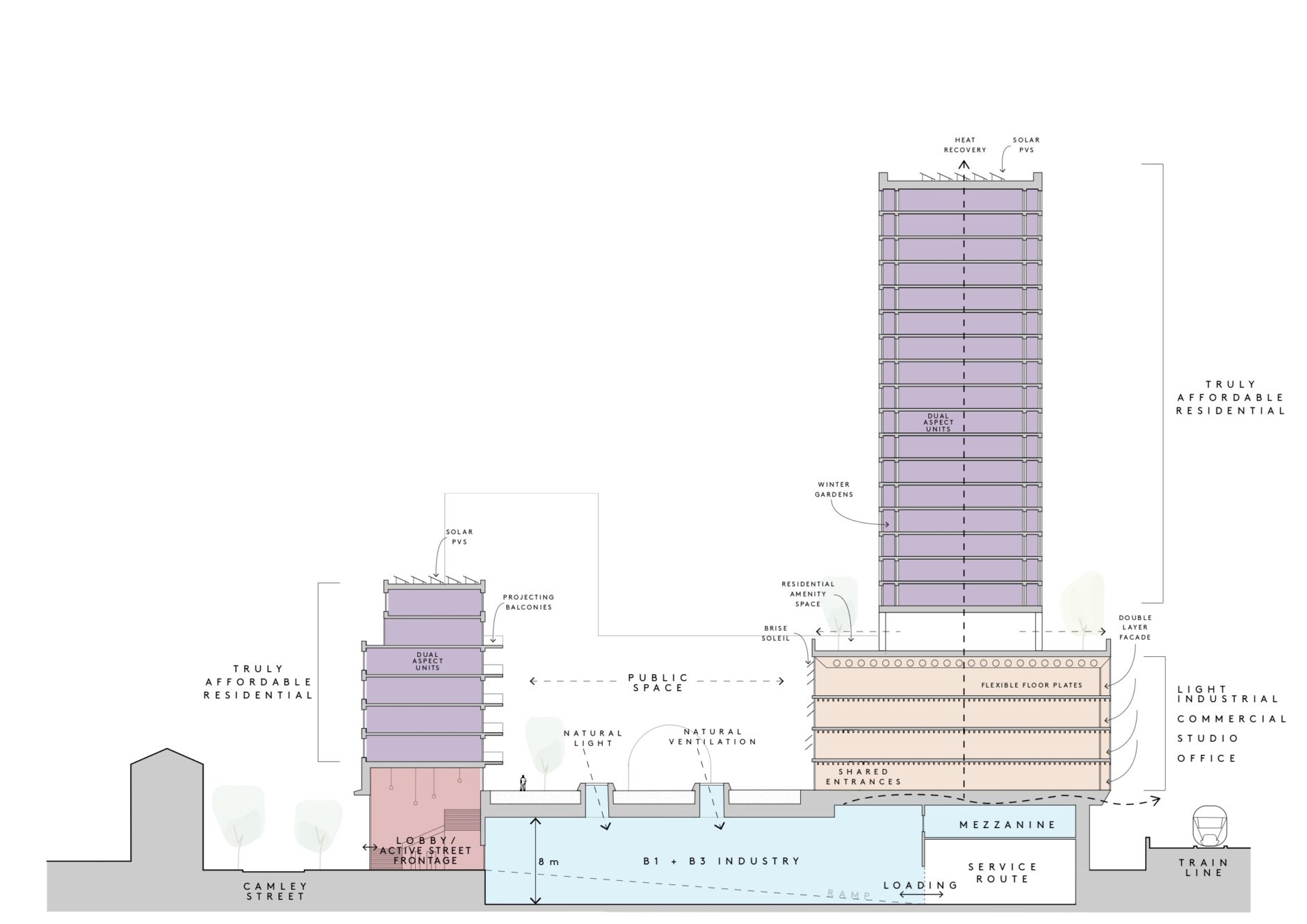

LB: What are the clear benefits of remasterplanning the Camley Street neighbourhood in King’s Cross as a Sustainability Zone led by the Neighbourhood Forum (NF) and in what way could it become an exemplar for a future Labour government? What could the NF’s powers help to avoid, or to mitigate? (a dominance of private sector student housing, for example)?

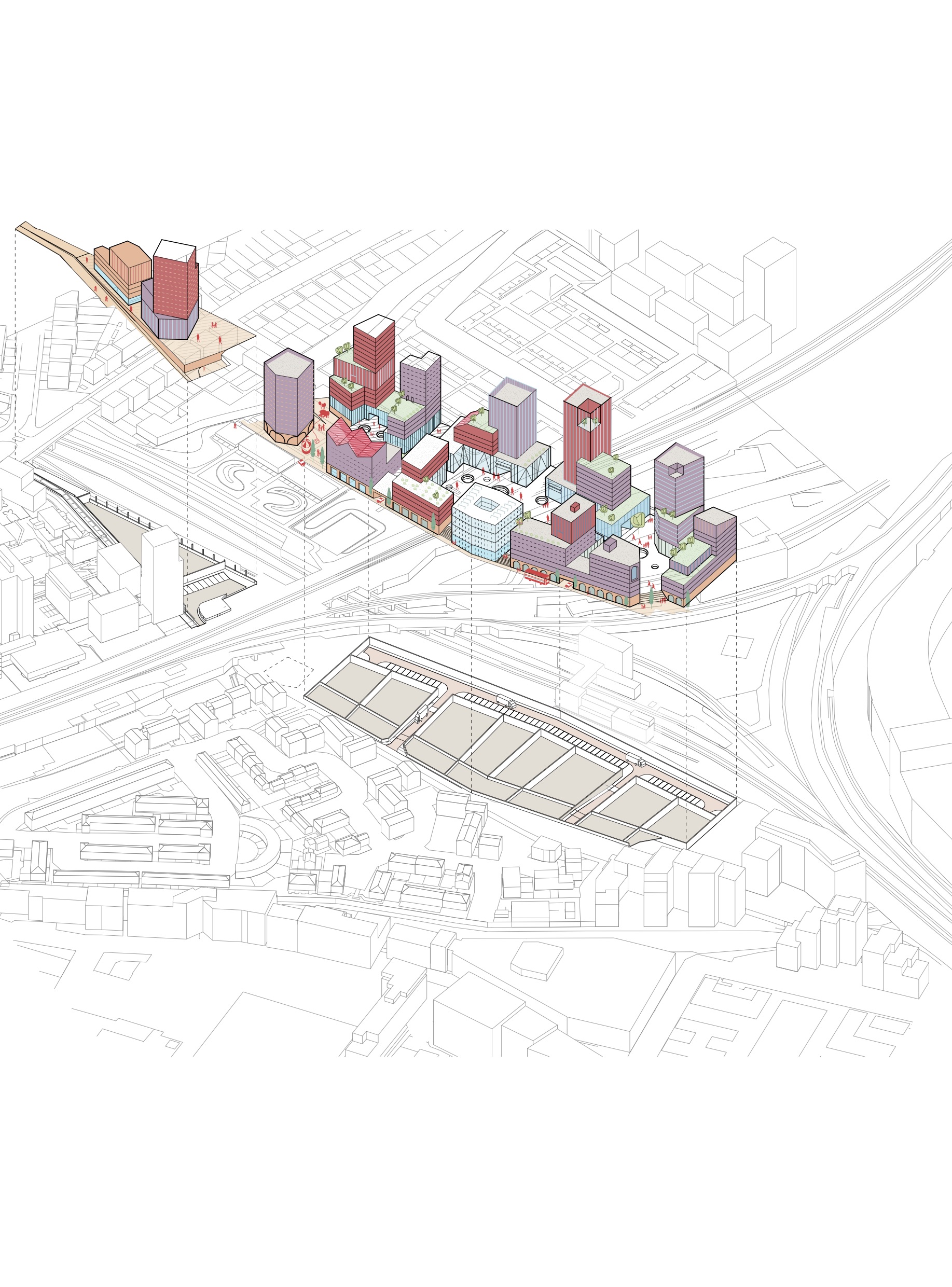

Exploded masterplan, Camley Street neighbourhood, King’s Cross, Karakusevic Carson Architects. © KCA.

PK: It is basically good city making. The benefit of remasterplanning the Camley street neighbourhood in the way that we are proposing is that the area will benefit from new activity, but that the new mix will not mean the end of the industrial spirit and diversity of what’s there now. It’s not just jobs, it’s urban life, linkages and social infrastructure. We are proposing a way in which these can work together.

Mix is why people love cities and building this into any development will future-proof neighbourhoods and towns. In the 2000s, too much of what was urban revolved around spectacle. The image of the city via a developer’s ‘place-making’ brochure, all neat potted plants and well behaved cafes with everyone subscribing to identical living, consuming and working patterns. That urban model is broken and its effects are nullifying. City governments need to read and embrace the city in its layers and nuance and seize the opportunities of such. Therein lies resilience.

Sketch view, masterplan, Camley Street neighbourhood, King’s Cross, Karakusevic Carson Architects. © KCA.

Section strategy, masterplan, Camley Street neighbourhood, King’s Cross, Karakusevic Carson Architects. © KCA.

King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council. © Tim Crocker.

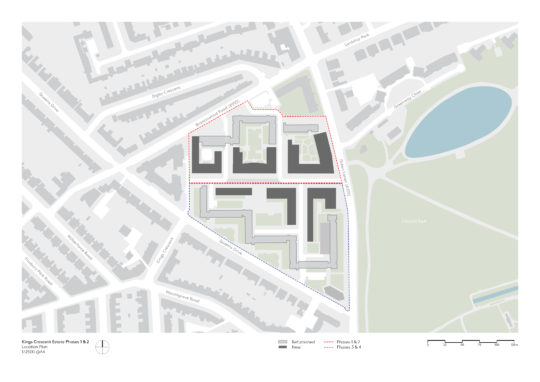

Location plan, King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council.

Drawing 1.1000 at A4 ground floor plan, King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council.

LB: 11 years ago you won the then Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s commission for affordable pilot council housing as part of central government giving local authorities the right to build and invest in their own stock. How did the brief for this pilot project seek to realise credible improvements? Do you recommend new pilot housing projects today as ways to test out alternative methods, and if so, can you give a few examples of what is currently missing?

King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council. © Mark Hadden.

PK: Absolutely, Gordon Brown was visionary in this respect, reversing 30 years of local government underinvestment in its own housing stock. Design and quality was all important in the briefing and the council officers at Barking & Dagenham Council were incredibly inspired in terms of the environment targets and living standards for new homes. The work that the GLA has done on design standards and officer training through initiatives like Public Practice should pay dividends in the coming years to ensure the local authorities have the highest calibre of staff.

King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council. © Peter Landers.

Smaller developers and co-housing groups and not-for-profit groups should be encouraged through government and GLA support to innovate on alternative routes, but ensure that design quality plays a major component in any evaluation. By doing this the wider industry will adapt and improve the housing it offers and the process it takes to produce it.

It is fair to say I am not an advocate of the big house builders in the UK and worryingly some of their crude approaches to housing are infiltrating Housing Associations (HA), which for me feels morally questionable and disappointing. HAs should be alongside local authorities in reclaiming their historic roles and leading the charge for innovation, quality and delivery.

King’s Crescent, Hackney, Karakusevic Carson Architects. Client: Hackney Council.