4

Issue 4

4

Issue 4

Mutual support: learning from dugnad and bayanihan

In a world threatened by increasing human and natural disasters, accelerated by excessive exploitation and extraction of resources, architect and participatory design expert Alexander Furunes argues that to advance mutual support it becomes increasingly important to find alternatives to existing decision-making structures – alternatives which that do not belong to the paradigm of economic growth. He advocates collaborative practices such as dugnad (Norway) and bayanihan (Philippines) to help give voice to those who normally do not have the power to influence decision-making.

We are currently living in times of interregnum’, claimed sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman, when the old structures of society have become irrelevant and the new ones have not yet been proposed. The main reason for this situation, he explained, is the separation of power from politics – ‘Power being the ability to have things done, and politics being the ability to decide which things needs to be done’. Until recently governments had both the power to do things and the political institutions to decide which things are to be done. However, this is no longer the case. In fact, ‘No one is in control, and that is the main source for contemporary fear’, leading to xenophobia, populism and the need for strong leaders that appear to know what to do (Bauman, Times of interregnum, 2012).

The laying of rooftiles on a house in Grimsbu, Norway, 1933. © Museo i Nord-Østerdal CC PDM.

The laying of rooftiles through tekkie-dugnad, Norway. © Hvamstad, Per/Musea i Nord-Østerdalen CC BY-NC-SA.

As power has moved away from politics to other centres of power, especially economic ones, important decisions for the future are made outside democratic control. With no real power, governments are left to ‘hive off, outsource, or contract out the growing number of functions traditionally entrusted to the governance of national governments to non-political agencies’ (Bauman, 2012).

Instead of the state providing for its citizens, now multinational corporations, financial and economic elites answer to the demands of shareholders and consumers. Architecture is built utilising natural and human resources and contributes to the paradigm of growth and financial speculation. The ability to decide how to build, who gets to build, where to build and for what purpose – these are all questions relating to power.

According to community organizer Eric Liu, power justifies itself by ‘creating an ideological narrative of why things got to be this way’ (Liu, 2017). Power also accumulates, and when left to itself, ‘a market economy will eventually put a massive share of total wealth into a very small number of hands’. Power is also self-legitimising as ‘the powerful will tell the tales about why they deserve their status,’ whether it is true or not, as when their stories are believed by the people they gain agency. In a world threatened by increasing human and natural disasters, accelerated by excessive exploitation and extraction of resources, it becomes increasingly important to find alternative understanding and narratives to existing decision-making structures that do not belong to the paradigm of economic growth.

Mutual work building a seterhus (log house), Norway, 1921. © Rachel Haarseth, Museo i Nord-Østerdalen, CC BY-NC-SA.

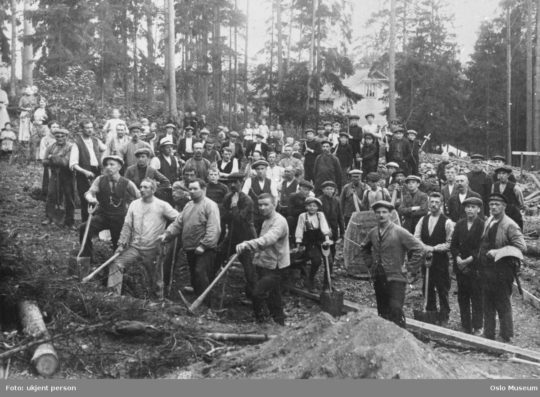

Collaborative traditions, largely in rural parts of the world, have offered a different perspective on how to get things done and how to decide what needs to be done. In Norway, the tradition of dugnad has been used for restoration, maintenance or for the management of organisations such as foreninger and lag. Historically, it has contributed to shape Norway’s modern-day labour unions and indirectly the welfare state. It was also used in the reconstruction efforts after the Second World War (Lorentzen and Dugstad, 2011).

Preparatory groundworks for building a cooperative in Høvik, Norway, 1915. © Oslo Museum, CC BY-SA.

Dugnad is a part of a tradition that predates the market economy. It is arguably as old as human culture. In organisational theory, dugnad is referred to as mutual aid, a voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services. It is differentiated from charity as it does not create a division of giver and receiver as people invest in a cause that mutually benefit them. Mutual aid exists in many forms around the world and has been a means to support each other through different seasons, natural disasters and conflicts.

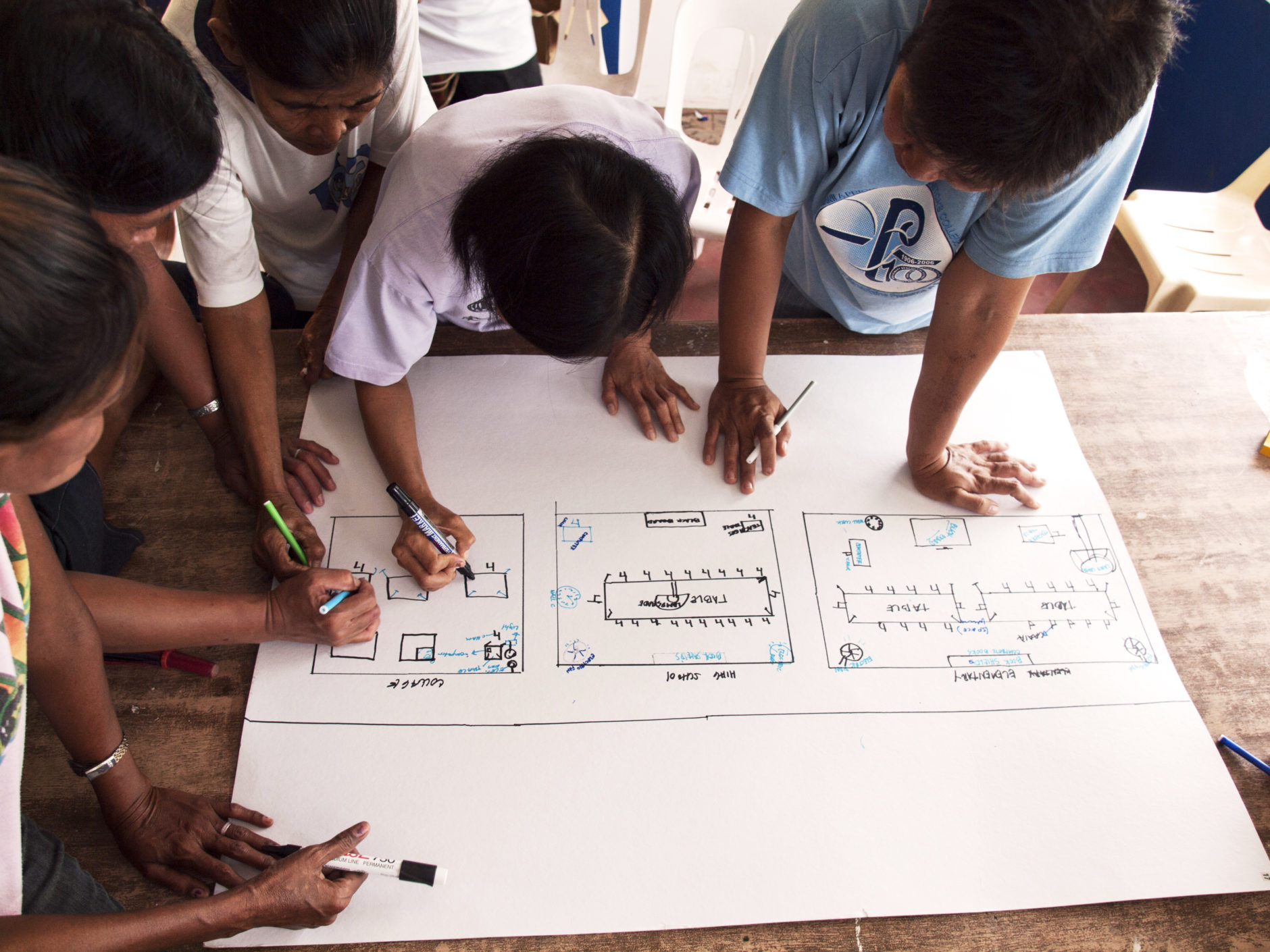

Planning and programming of a study centre in Tagpuro, Philippines, 2016, a process inspired by dugnad/bayanihan. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

Collaborative design process inspired by bayanihan, 2010. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

Construction of a roof of a study centre in Tacloban, Philippines, 2010. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

Another example of mutual support is the Filipino bayanihan which is mainly practiced whenever local communities need to make a collective effort to build schools, host weddings and funerals among other things. The term mutual support was first introduced by activist and philosopher Peter Kropotkin to stress the value of cooperation over that of the Social Darwinists and their description of individual struggle and competition (Kropotkin, 2012).

Modelmaking for new textile cooperative, Lung Tam, Vietnam, 2018. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

The building process in Vietnam is very similar to the Norwegian tekkjedugnad, 2018. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

Mutual support has throughout history been a mechanism for survival amongst animals as well as human societies and contributed to the evolution of social institutions such as trade unions, cooperatives and other civil society movements. This tradition is rooted in solidarity and reciprocity and has been central in giving shape to the anarchist movement in the late 19th century. On the other hand, mutual support has also been used by neoliberals as an argument that communities can provide for themselves, and that government support is not needed. The 2011 Localism Act of former UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s Big Society is one such example where government delegated its own responsibility to the community.

Mutual work to design and build a school in Hariharpur, India, 2013. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

Although mutual support has been used as a means for both leftist and conservative agendas, it reclaims decision-making power for the local communities where resources belong. In mutual aid societies, buildings were built through access to environmental and social capital. Depending on the building materials available, you could mobilise members of the community to come together and help with construction. The operation and maintenance of buildings relied on the ability to sustain environmental and social capital. Food and celebration were part of the process of building because they strengthened social ties, and the materials used would be replenished years or sometimes generations in advance, to ensure access when renovations or changes are needed. Knowledge and craft were passed on through generations in the forms of stories and collective work. The inter-generationality of dugnad, the knowledge exchange between different competencies of participants both create conditions for a deliberative process necessary to battle alienation, apathy and the delegation of responsibility.

Building an orphanage in Tagpuro, Philippines, 2016. © Alexander Eriksson Furunes.

Mutual support gives value to solidarity and reciprocity over monetary currency, reflecting social relations, knowledge and natural resources present in the specific locality. This model of organisation can give shape to new power structures that can trigger dialogues with an equal standing to powerholders such as the government, international organisations, aid organisations or outside interest groups acting on behalf of the people. This is because mutual support can give voice to those who normally do not have the power to influence decision-making.

According to anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker, this power shift caused by mutual support is exactly what happened when the working class started to organise themselves into labour unions during the first Industrial Revolution (Rocker, 2004). In today’s world, it is crucial to create a new power structure where local communities can hold national and global governing bodies accountable in order to address inequalities and social injustices weakening our delicate social fabrics.

Bankoff, G. (2007). ‘Dangers to going it alone: social capital and the origins of community resilience in the Philippines.’ Continuity and Change 22 (2): 327-355.

Bauman, Z. (2012). ‘Times of interregnum.’ Ethics & Global Politics5(1): 49-56.

Kropotkin, P. (2012). Mutual aid: A factor of evolution, Courier Corporation.

Liu, E. (2017). You’re More Powerful Than You Think: A Citizen’s Guide to Making Change Happen, PublicAffairs.

Lorentzen, H. and L. Dugstad (2011). Den norske dugnaden: historie, kultur og fellesskap, Høyskoleforlaget, Norwegian Academic Press.

Rocker, R. (2004). Anarcho-syndicalism: Theory and practice, AK Press.