2

Issue 2

2

Issue 2

Inside Inside Out. (Photo © Royal Academy of Arts)

Inside Out: Richard Rogers – an architect on message and medium

What do you do with a celebratory exhibition about your work? Use it as an opportunity to convey messages, a soap box, a meeting point of all the things you hold dear, stir people up.

Inside Out: Richard Rogers, the Royal Academy of Arts’ exhibition, which opened on 18 July 2013 and has recently closed, coincided with his 80th birthday. As a member of the Royal Academy since 1978, he is its most naturally outspoken architectural member. Ideas and ethos, exploring his social, political and cultural influences, support everything on show. ‘I feel that what one stands for is more important than what one achieves’, Rogers told The Evening Standard in July. Now that is not entirely the case, but you see the point: most architects have to compromise to get ahead, and the fates of buildings and urban designs are not in their hands.

Portrait of Richard Rogers. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

Rogers even had to defend the central business district Barangaroo, a major project for Sydney, on which his practice RSH-P is working earlier this year, and from which another stellar, socially focused architect, Jan Gehl, has now bowed out due to its commercial focus, against claims that it represents ‘the worst of Dubai’. Rogers is a luminary figure in the architectural world who has since his early days worked with themes far wider than conventional architectural thinking, articulating them as a spokesperson, writer, politician and activist, as well as an architect. His practice RSH-P, 180 people strong across three offices in London, Shanghai and Sydney, adheres to a ‘collegiate’ approach, with measures including a 20 percent profit-sharing scheme and significant contributions to charity.

Outside Inside Out. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

He has said the most about London, where he lives, and where he got his second urban commission after the groundbreaking Pompidou Centre – the Lloyd’s building – at a time when most of the practice’s work had been lightweight industrial buildings on greenfield sites. At the heart of the exhibition is a two dimensional display of diagrams about London, articulating a set of proposals: reclaim the high streets, build mixed use developments on brownfield sites, grow the transport network, retrofit and intensify London’s 600 localities, protect the Green Belt and reinforce the network of green and public spaces in London. Things have been happening: Mary Portas made a game attempt not long ago at a high street revival plan, the transport network is being expanded in a myriad of ways from Crossrail to new Overground rail stations; however, back in the mists of history, the previous London Mayor Ken Livingstone’s 100 Public Spaces scheme was thrown out, and while there is the ongoing East London Green Grid Framework scheme, and a proactive Garden Museum that mounted a competition for the proposals for a London version of the High Line, there isn’t a cross-borough campaigning network for green public spaces.

Inside Inside Out. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

Many people know about or have taken the bus past the massed façade of RSH-P’s scheme for the Candy brothers, One Hyde Park, 86 luxury apartments in four pavilions, a job that will have helped the practice’s profits, but fewer know about their design for Newington Butts, a large-scale high rise rental housing, with affordable units run by Peabody, and long leases, more common in the United States, which is due to be ready in 2017. Neither project was included in the exhibition. Clearly it was carefully selected to present a set of messages (which it does with a lacing of fine attitude: when Philip Johnson asked to see a plan when he visited, Rogers answered, ‘the section drives the building’), but tensions at the boundaries of such a famous practice raise a range of questions about the directions in which its formidable skills are aimed in the future.

Inside Out Explained. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

This is important, because Rogers wants to remind us that it is possible to think very differently about affordable housing in the future, given that there is an urgent need for it. In London in particular, he regards it as one of the most important issues the city is struggling with. On 13 August, nearly a month after Inside Out opened, boxes of flat pack panels delivered to the Royal Academy were transformed within 24 hours into Homeshell, a 1:1 example of a three and a half storey, low-cost house put up in the Courtyard outside Burlington House, ready for visitors to explore its interiors and a timelapse film of its construction.

Examining the Architecture. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

Unfortunately, the developer must have needed this prototype back, because it was removed weeks before the closing date when the project could have had a display of this kind in place until the exhibition ended. It could have had more focus on Rogers’ highly credible bid to create practical solutions for the use of brownfield sites for housing, which in the United Kingdom represent a total of 63,750 hectares, of which 51% is derelict or vacant (2013 figures). The urban design section of the exhibition stated that London alone has 3600 hectares of brownfield sites, enough for an estimated 500,000 houses at medium density, many of them in East London in places like Rainham, Dagenham, Barking and Southall.

Up Close. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

Homeshell uses a flexible, quick and highly energy efficient building system called Insulshell, also used inside the Velodrome at the London Olympics, and much faster than traditional house-building methods. Because they are adaptable to traditionally difficult locations or small sites in urban contexts, the housing enables more urban brownfield sites to be coopted for homes, utilizing existing transport and infrastructure links instead of encroaching on the Green Belt. The advantages of Homeshell include its generosity of space, exceptional levels of insulation and daylight, and quality of acoustics. This solution, so incongruous in front of the historic fabric of RA, was dismantled and rebuilt as the show house of the YMCA South West Y:Cube Housing project designed by RSH-P, in Mitcham, Surrey.

London, the Compact City. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

Designed by Rogers’ younger son Ab Rogers with graphics by Graphic Thought Facility, Inside Out was grouped by the curator, Jeremy Melvin, in four rooms broadly clustering architecture and history, urban design, and a video projected to visitors. This final salon, like the initial entry space (of ethos statements), was kitted out with large bright pink upholstered furniture on which to view director Alan Yentob and Richard Rogers touring various buildings while in conversation.

Pressure on London. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

While the architecture rooms were dense scenes of achievements, memorabilia with many of Rogers’ notebooks full of scrawled notes and diagrams, a real treasure trove if you spent time to read them, the urban design room was huge and left deliberately somewhat empty to allow space for visitors to add their comments on what they desire for London’s future on labels stuck on the wall. That growing cloud of wishes by the end of the exhibition had become like a huge wisteria across three walls and over part of a serried row of big green steps where the tired could rest and children could play with a box of LEGO, already partially assembled as an array of brightly coloured, decorative tall buildings.

Coffee Commons at Inside Out. (Photo (c) Royal Academy of Arts)

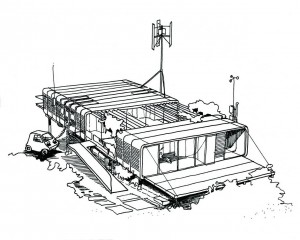

The architecture room was bedecked with impact-making period titles like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the Last Whole Earth catalogue. The column-free, flexible Inmos factory, for Newport, the 1968 Zip Up house, a built prototype designed with Su Rogers, made from insulated panels used for refrigerated trucks, very easy and quick to build, demonstrated the seminal influence of Walter Segal, Buckminster Fuller and others, as well as being a resourceful starting point Rogers has clearly returned to.

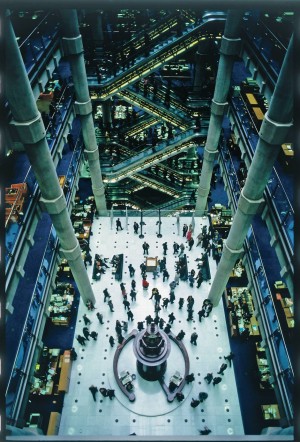

Richard Rogers Partnership, Lloyd’s of London, 1978-86. Looking down into The Room. (Photo © Janet Gill, courtesy of the Estate of Janet Gill)

The lesser known cues were stimulating: here one could glimpse a 1979 Autonomous House, for Steve Martin, responding to climatic stimuli, there, The Spirit Level, Richard Williamson and Kate Pickett, the 2009 book on equal societies. From the thread of media coverage and memorabilia on the back walls, it was clear that Rogers made quite an impact with his 1995, 1997 and 2000 Reith Lectures. It would be timely to give another architect the spotlight to delve into the knotty issues of architecture and its social mandate next year.

Richard Rogers Partnership, London As It Could Be, 1986. Creating a new public realm, Embankment, London. (Photo © Richard Rogers Partnership courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners)

The exhibition’s urban design room included a few artefacts for a speculative scheme for Florence, where he was born. The Arno River, cut off by walls, inaccessible, gets new access routes to surrounding streets and squares with lightweight floating structures, including a new bridge by Peter Rice, engineer and collaborator on the Pompidou Centre, to conveniently sink out of the way when the river flooded. We miss this genre of ingenious can-do structures in public life today, and Florence would certainly have been given a good shake-up had this one been implemented.

Richard + Su Rogers, Zip-Up House, 1968. Concept drawing. (Photo © Richard and Su Rogers, courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners)

The practice’s response to Sarkozy’s 2007 invitation to take part in his Grand Paris speculation, a new comprehensive development project (that never was, in the end) makes quite an impact if you can stay and watch all the dynamic graphics. It showed that those who advocate junking big master plans as a tactic and only focusing on the smaller scale are potentially wasting the capacity of architects like Rogers and co to analyse and come up with highly credible propositions for an entire city.

Richard Rogers Partnership, Terminal 4, Barajas Airport, Madrid 1997-2005. Coloured structural ‘trees’ in the airport terminal. (Photo © Manuel Renau, courtesy of AENA and Manuel Renau)

The diagnosis made, both in rigour and values, is applicable to many cities, not just Paris: ‘the spread of the urban footprint has been unconstrained’. Whether they are realized is another matter, but the desire to find synthesis is dramatically evident in the info-graphic layers backing up Rogers’ mantras: build on the brownfield sites; reinforce the suburban polycentres (from existing nodes), rebalance the city, especially its green spaces and create a green grid of public spaces, and create new eco-armatures (using a noun David Grahame Shane uses in Urban Design since 1945 – a global perspective, his 2011 book, who calls it a ‘linear spatial organizing device…containing and sorting flows’, applicable at a variety of scales and potentially combined with an ‘enclave’), maximize mixing of uses and add new circumferential lines to the transport network. The scheme proposes 1000 new smaller urban projects, e.g. the Axe du Nord, and grouping the polycentres more closely with armatures, interfacing between ‘communes’.

This is far more than just arbitrary: the plan deals with social disparities, with notional investment inserted in the poorest places (the centre and the west have the high value jobs currently), and proposes to apply a district heating network to the whole city, and place new public spaces over existing rail arteries.

The Shanghai display was a vision of the sustainable, compact city, while London, on the next wall, is of course where Rogers lives. Its wall displays called for sustained concentration to fathom the points of diagrams. In the development of London’s transport network, Rogers feels emphasis should be on new networks, incorporating the under-served east end, and a map singles out areas of poor connectivity, and he also advocates new forms of micro-vehicle. ‘Areas with the best connectivity will see the strongest growth’, he states of London, a polycentric city, which is ‘particularly appropriate for a compact city.’

What will be the effect of more balanced access to housing, education, work and leisure across the city in the next few years as the population of London continues to rise? Rogers sees London as an amalgam of 600 individual localities, from Uxbridge in the west, to North Ockenden in the east, Waltham Cross to the north, and Biggin Hill to south. Its streets, all 600 miles of them, if fully reclaimed for public use, with new types of building, could help consolidate cores of polycentres, hubs of employment and residential clusters. It fell to the Grand Paris scheme to try to show the synergy of these various concepts more dynamically through video info-graphics – a missed opportunity to take London to this level of dynamic graphic messaging.

Rogers, one could say, is frequently Inside Out, and on message, in his views. His comments on architecture and planning issues are regularly reported or published as essays in the public arena of national media. This year alone, apart from his latest vigorous advocacy of using brownfield sites for new housing needed, back in March (The Guardian, 26 March 2013, Robert Booth), he was quoted on the subject of local council cuts.

He warned that their wide extent (according to Guardian research, as much as 50% from their planning budgets between 2012-2014, with some of the biggest city councils cutting the most, e.g. Manchester, by 54%; Portsmouth, by 49%, and Liverpool by 35%) would undermine Downing Street’s localism policy intended to give community groups more decision-making powers when it comes to the future of their area. ‘The success of localism depends on knowing what you are doing, so if they don’t put money into expertise in local areas, who will make the decisions?’ he asked. ‘The public can’t be expected to run planning. You need well-informed, well trained planners taking these decisions.’

Who get the power to make key decisions about locations in such a situation is likely to be developers making applications to the councils. It’s a contentious issue raising the ironies of the localism agenda, given the government’s recent requirement for councils to produce local plans outlining the numbers of houses they will build between 2013-8 within a strategic planning framework for specific areas of cities. But without sufficient staff at local council planning departments, applications for planning will in fact end up being decided centrally using broad national planning policy criteria, making any ‘localism agenda’ rather insubstantial, since it is highly likely that communities will not get the kinds of developments they want.

Rogers has left a huge mark on cities, especially London: after the Lloyd’s Building the Partnership did the progressive, mixed-use Coin Street development on the South Bank in 1979-83; in 1987 his response to the redevelopment of Paternoster Square next to St Paul’s Cathedral was ‘scuppered’, as Melvin puts it, by ‘princely dark powers’. Today Rogers maintains that ‘London must not be abandoned to the mercy of the market – to cars, pollution and poverty’. His influence is evident in the London Plan, guiding future development, and he continues to campaign for a more livable city.

London is one that gave him succour (albeit that tough, utilitarian schooling until he went to the AA, when the tutors initially gave him low grades – as a certificate displayed in the exhibition attests) when he moved with his family (his father became a National Health Service doctor) to England in 1939 from Florence. But what next? Inside Out leaves us wanting more from the robust, indefatigable Rogers platform, from the rebel with a cause, who helped to change what we thought we believed about architecture’s place in the world, and its courage to do things without fear, in so many ways.

Lucy Bullivant Hon FRIBA is a leading architecture curator, critic, author and consultant who investigates and evaluates innovative synergies in contemporary architecture and urban design between theory and practice across cultures. She works internationally with leading museums, galleries, cultural and educational institutions, publishers, corporate and non-profit bodies, and in February 2013 founded Urbanista.org, a new webzine of critical analysis of urban design. She is Adjunct Professor in the history and theory of urban design, Syracuse University in London, autumn 2013.