2

Issue 2

2

Issue 2

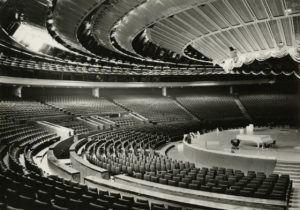

The auditorium could hold 4600 people and has been used for everything from rock converts, to political rallies to Jehovah’s Witness meetings. (Photo © Museum of Estonian Architecture)

Recycling Socialism, Tallinn Architectural Biennale 2013

‘Recycling Socialism’ was the theme of this year’s Architectural Biennale in Tallinn, Estonia. In an effort to reflect Estonians’ conflicted relationship with the country’s Socialist past, curators hosted exhibitions in some of the capital’s most iconic and problematic buildings.

All over Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia, the landscape is dotted with the legacy of the socialist built environment. These structures have vastly different composition and worth. Some are still in use, having found life in various guises, usually from their utility in the market economy. These buildings are the ‘winners’ that have made the jump from earlier plans and uses in the collectivist system to functionality in contemporary circumstances. Many structures, however, are not deemed of value in the post-socialist world, and constitute a problem.

The exterior of the Linnahall at Tallinn’s seaside. The multiuse venue, designed by architect Raine Karp, was built for the sailing competition of the 1980 Summer Olympics. Since the 1990s it has steadily fallen into disrepair. (Photo © Michael Amundsen)

Recycling Socialism, the 2013 Tallinn Architecture Biennale (TAB), organized by the Estonian Centre of Architecture, addresses the socialist architectural legacy of Tallinn. It is a diverse programme put together by curators Kaidi Õis, Karin Tõugu, Kadri Klementi, Aet Ader, and Mari Hunt, that seeks a critical appraisal and solutions to Tallinn’s Soviet era buildingscape. The focus of TAB 2013 is Tallinn’s modernist spaces built from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Aerial view of the Tallinn Linnahall. The design has been compared to a medieval bastion, bunker and ziggurat. (Photo © Museum of Estonian Architecture)

A unique aspect of TAB 2013 is that all key events from the first week of the Biennale were held in venues which are of the era focused upon. For example, the curators’ exhibition was held in the Sprat-Tin Hall in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Vision Competition in the Väike-Õismäe neighborhood of Tallinn, a compact micro district built in the 1970s in an oval shape, was a pop-up exhibition in an empty Soviet era school building. The Biennale’s symposium was held in the period cinema Kosmos, and the architecture school’s exhibition was brought to the Tallinn Linnahall, a massive multi-use structure made for the 1980 Summer Olympics. Of these venues, the most spectacular and problematic is the Linnahall, which finds itself in a netherworld between various, ill-defined plans and an urban ruin.

In the 1990s a heliport and small ferry terminal were added to the rear of the Linnahall. (Photo © Michael Amundsen)

In Estonia there is a strong consciousness of the political origins and ideology of architecture from the Soviet era. The Soviet occupation of Estonia is viewed as a national tragedy, and thus prominent public works from this historical period were commonly seen through a prism of resentment against that built environment and what it represents. This can make rehabilitating buildings from this era problematic and politically very sensitive. For younger Estonians this mindset is far less prevalent, which allows for the appreciation of Soviet-era Estonian architecture without the attendant political baggage and with perhaps the hope of ‘recycling socialism’.

The Linnahall’s exterior is still very much a living space and finds many visitors for various pursuits. (Photo ©Michael Amundsen)

The Linnahall was christened the V.I. Lenin Palace of Culture and Sport and used as the home of the Olympic sailing competition in 1980. Raine Karp, the most important Estonian architect of Soviet modernism, headed the project. It is interesting that Karp’s description of influences for the building’s design have changed over time from ‘Japanese Metabolist architecture’ when the building was being considered, to a medieval bastion in more recent utterances. It is true that the building resembles a bunker and does look something like the Swedish bastions found in Tallinn, thus making the Linnahall contextually appropriate. The building included a concert hall, an exhibition hall, a bowling alley, eateries and a massive rooftop space for strolling and visiting, with beautiful views of the Baltic Sea. The project was grandiose in scale and composition and opened up the seafront from its industrial surroundings. This location meant the structure was built low to the ground to ensure that views of Tallinn’s medieval centre from the sea would remain unobscured. The best way to get a sense of this ambitious project is from an aerial view.

The electronic clock at the entrance to the Linnahall. It adds to the uncanny effect of futuristic obsolescence that the building conveys. (Photo © Michael Amundsen)

From auspicious beginnings – the Linnahall was given a Soviet State award and a Grand Prix from the Interarch World Biennale in Sofia in 1983 – the building fell into popular disfavour. It was seen as an alien intrusion in Tallinn’s landscape and, after independence in 1991, as a reminder of Soviet repression. But nostalgia intruded as well, as people’s personal memories were invested the building. The Linnahall remained a venue with diverse activities: a heliport and small ferry terminal were added, and variously a bar, disco, concert venue, and a meeting hall for political parties and Jehovah’s Witnesses were in use. All the while the city of Tallinn retained title to the structure and sought a private developer.

The interior of the Linnahall in its heyday. (Photo © Museum of Estonian Architecture)

By 2004, a potential investor was found who wished to demolish the structure and replace it with a posh residential district. The concert hall, however, was listed as a protected monument, scuttling this scheme. No definitive plans have emerged for the Linnahall. This doesn’t stop the space from being used by the public. Visitors are frequent, especially on nice days, and workers from surrounding areas can enjoy their lunch hour with a view of the Baltic Sea. Graffiti artists make the Linnahall their canvas. The unusual contours of the structure make it a site of recreation for parkour enthusiasts. Tourists often stumble here from the nearby passenger port by accident, invariably asking, ‘What is this?’ The Linnahall is a popular spot to have a beer and simply hang out. In this sense the structure has already been ‘recycled’.

The auditorium could hold 4600 people and has been used for everything from rock converts, to political rallies to Jehovah’s Witness meetings. (Photo © Museum of Estonian Architecture)

Entering the Linnahall, the visitor is struck by an intense musty odour. There is an electronic clock ticking away, as if the building still had some functionality. An attendant sits in a glass enclosure. The Linnahall’s interior is only open by special appointment, so his job is most often to tell people to leave as the building is closed. The sense the inside of the Linnahall presents, like much of Soviet modernism, is an attempt to grasp the future in architectural space, or of science fiction. There is a fantastically massive coat check in the curved space in front of the concert hall. The concert hall itself is in a state of disrepair. The stage is heaped with junk. But the feeling of the former grandeur of the place is evident.

The Tallinn Linnahall was originally called the V.I. Lenin Palace of Culture and Sport. (Photo © Museum of Estonian Architecture)

Michael Amundsen is a doctoral researcher at Tallinn University’s Estonian Institute of Humanities. His work concentrates on urban spaces and their meanings with particular attention to Soviet and remnant German landscapes in Kaliningrad, Russian Federation. He has written on Estonian, Baltic and Russian culture for Estonian Public Broadcasting, the Christian Science Monitor, the Financial Times, Vice and others. He is co-editor of the biannual magazine Tallinn Arts.