2

Issue 2

2

Issue 2

Old Bucharest: street scene from the early 1900s. (Photo (c) Gruia Badescu)

Shaping the City: scars and sutures

A comparison between urban initiatives in Bucharest, post-Socialism, and London, post-Localism, reveals how politics can shape the urban fabric.

Bucharest is a city in which the scars of its political past are evident within the urban fabric of its present. For much of the 20th century, Communist dictators ruled Romania with an iron fist. In addition to adopting policies of alleged ‘assimilation’ and ‘equality’. Romania’s leaders sought to make their mark on the country’s cities. They forced inhabitants of Romania’s lush countryside to move to metropolitan areas, and erased large swathes of the existing urban infrastructure in order to erect monuments to Communism. Grand boulevards, and even grander buildings seemed more appropriate to a monarchy than to the supposed Socialist system.

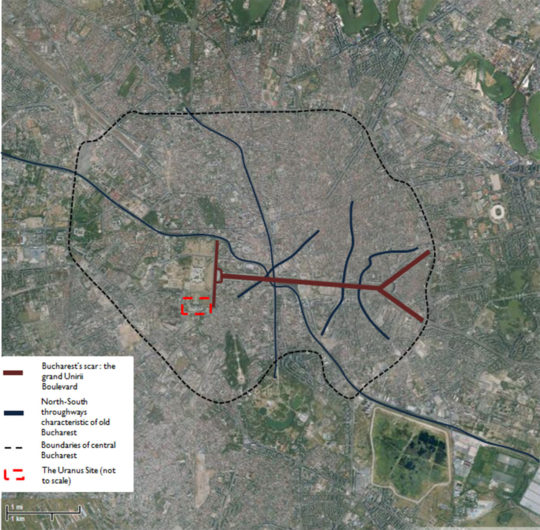

Bucharest, Romania’s capital, was the city most affected by these changes. The destruction of north-south throughways to create east-west highways, the erection of Socialist blocs replacing Belle Époque homes, and the construction of ostentatious government buildings in lieu of small-scale Orthodox churches transformed the city from the ‘Little Paris’ of the early 20th century to the ‘Eclectic City’ of the 21st. The changes left a scar on the cityscape, bisecting the city into a northern, more prosperous half and more deprived neighbourhoods in the south.

New Bucharest: minimalist buildings, street cars, electrical wires, and vehicles characterize contemporary Bucharest. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

The city’s scar, as well as its architectural eclecticism, serves as a constant reminder to Bucurestis of their past oppression. For visitors to the city, the seeming randomness of the streets, the disjointedness between decaying, but beautiful, Belle Époque homes organized around churches and parks and the palatial government buildings surrounded by nothing, seems only to indicate the government’s totalitarian control of the city and its planning.

Buildings from Old and New Bucharest sit side-by-side, allowing for architectural comparison. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

Little has changed regarding the structure of the city during the past 20 years, although much has changed politically. The fall of Communism and the subsequent rise of a capitalist democracy have introduced a greater overall level of public political participation in the country – so much so that the European Union awarded Romania with full membership in 2007. But interviews with government officials, academics, and NGOs reveal that the concept of participatory planning is still little known in Romania, particularly in Bucharest. Planning decisions are made mostly by the city’s urban planning department, which, in turn, is greatly influenced by the Mayor of Bucharest, who, in turn, is affected by the wishes of the business community and the promise of a more prominent, national political post. Citizen participation – in any formal way – is more or less a myth. Community hearings are scheduled to take place in halls too small for non-members of the media to attend, so citizens are often relegated to watching the live stream from a nearby room, unable to ask questions of the policymakers. The subjects of those hearings, generally demolitions of community landmarks in areas officials deem more suitable for yet another car-centric, transport project, are carried out without citizen approval: they happen during the week, under the cover of night, or at any time when few witnesses can emerge to protest government actions.

Protestors gather on a street in central Bucharest, demonstrating against recent government initiatives. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

Some NGOs organize in opposition to these changes to Bucharest, inciting others to become involved in their neighbourhoods, to actively shape their surroundings, and to protest the government’s continued imposition on the urban landscape. They loudly broadcast the word through meetings, lectures, and social media in the hope that the new generation of Bucurestis will not willingly accept the government’s plans as their parents were forced to, and in some cases, their messages break through.

The ‘Scar of Bucharest’ with Uranus site inset. (Photo (c) Google Maps with author’s augmentation)

The neighbourhood of Uranus sits squarely in the middle of these opposing forces: Bucuresti NGO’s call for greater public participation in planning and the government’s urban planning agenda promoting any initiative that would enhance the city’s business sector. The few blocks composing the Uranus site lie in a strategic position for development: the dividing line between Bucharest’s prosperous northern half and its poorer, southern region. They are just south of Bucharest’s ‘scar’, which includes the Palatul Parlamentului (‘Parliament’s Palace’ or the ‘People’s House’), the second largest building in the world; the National Academy of Sciences, a half-finished building constructed solely to perpetuate the myth that one of the Communist dictator’s wives was an accomplished chemist; and Unirii Boulevard, the prominent east-west boulevard bisecting the city. They are just north of the neighbourhoods of Bucharest’s Roma population, perceived to be seedier and more dangerous places.

The Palatul Parlamentuili, Ceaucescu’s famed monument. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

Aware of the area’s vulnerabilities, a concerned group of citizens formed a coalition of architects, planners and NGOs to draw up a plan that not only charted the renewal of the Uranus site, but also envisioned a more liveable, sustainable central city. Within the neighbourhood, the plan included a public park, a permanent structure for the now-temporary flower market run by Roma, investments for start-up ventures and affordable housing. In the central city, the plan provided for maintenance of public parks, sidewalk extensions, cycle lanes, and underground parking, among other improvements.

The National Academy of Arts and Sciences, built to appease Ceaucescu’s wife. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

Given the city’s history of monolithic decision-making, the city government, surprisingly, heard and accepted this scheme by the group, known as the Associatia Spatia Urban Bucuresti (SUB), adopting its first two phases: design and project feasibility. However, the planning department chose not to adopt (at least not yet) the project’s arguably even more important phases of implementation and evaluation. In the meantime, the city government has approved another plan for the central city. Put forward by a group of academics, planners employed by the city, and politicians, this plan, in rough terms, prompts the destruction of public space in favour of building more bridges and roads to facilitate suburbanites’ commute to the central city. Not only will this plan most likely divert attention and resources from the citizens’ proposition for the Uranus site, but it also in certain areas directly conflicts with it in spatial terms and in vision.

Old brewery buildings, now lie abandoned on the Uranus site. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

In my opinion, unless the SUB is able to raise funds from private investors, there is little hope that the redevelopment of the Uranus site – as monumental a contribution to participatory planning in Bucharest as it would be – will take place any time in the near future. The weight of a long history of government imposition on citizens’ built environment runs against it, and combating these forces with only citizen support might simply be insufficient. Rather, the group’s best chance for reversing the trend might be to partner with an unsuspecting ally: Bucharest’s burgeoning private sector. Since capitalism has taken hold of Bucharest, one potentially positive result has been the ability of citizens to shape the city’s development through consumption. Although I do not condone passive consumption of cities over active participation, I do recognize that, for Bucharest, a city where public input has previously been forbidden or punished, even consumer activity counts as a step towards more direct involvement.

The Ark, the Uranus neighbourhood’s centre for creative industries. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

Seemingly a million miles away, a different community group, supported by its local and national governments, recently filed for legal recognition of its status as a neighbourhood planning group run entirely by citizens. The Chatsworth Road Neighbourhood Forum is a coalition of more than 21 residents, business owners, and local politicians who live or work near Chatsworth Road, a small high street in the Clapton neighbourhood of London’s Borough of Hackney. While the area used to be known as ‘Murder Mile’, it has since been transformed by the city’s growth. The population, once homogenous, is now more ethnically and socio-economically diverse, and the neighbourhood exemplifies how the density required by urban settings can often lead seemingly disparate communities to co-exist peacefully.

The Uranus neighbourhood’s flower market, operated by mainly Roma merchants. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

When the traders who sold their wares at Chatsworth Road’s revived Sunday market heard about the United Kingdom’s Localism Act of 2011, it seemed the perfect legitimation for establishing their group. The intention of the Localism Act was ‘to disperse power more widely in Britain today’ (according to David Cameron, the Prime Minster and Nick Clegg, Deputy Prime Minister of the UK government’s formal coalition established in May 2010). In endowing new powers to local government, removing ‘roadblocks’ to their efforts to be innovative in urban planning, and empowering citizens to plan their communities, the Localism Act promised to do just that. Whether the Localism Act has succeeded yet or will succeed in the near future in its mission – and even whether the Act is a good and well-formulated one or not – is beyond the scope of this article to opine. What is important, though, is that the Localism Act’s provisions enabled groups of citizens, such as the Chatsworth Road Neighbourhood Forum, in an unprecedented way, to form authorized committees that could potentially impact the growth of their communities. Unlike Bucurestis’ constant struggle against the government to have a say in the city’s development, Londoners were ostensibly gifted with the right to do so.

An upscale home shop moves in next to an off-license store on Chatsworth Road. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

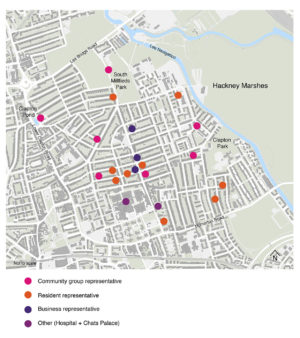

What was a small team of market traders interested in the development of Chatsworth Road Market grew into a larger group of residents, local business owners, and Borough politicians interested in preserving the area’s diverse nature, while allowing for positive change. Under the leadership of one diligent local resident, Euan Mills, the Chatsworth Road Neighbourhood Forum (CRTRA) drew its geographical boundaries; conducted neighbourhood hearings; solicited input from community, business, and political leaders via workshops, surveys, and informal consultations; set up a clear, transparent website about the Forum, including a blog where members discuss the CRTRA planning vision, its ethos, its meetings, its members and the activities of the street market; and even worked with students from a local academy on a project considering the neighbourhood’s future.

A BMW parks at the Chatsworth Laundrette. (Photo (c) Jon Broderick)

The vision statement CRTRA created from these outlets reflects the group’s emphasis on participation. As articulated on its website, the Neighbourhood Forum envisions Chatsworth Road as diverse, accessible, independent, sustainable, and sociable. It views Chatsworth Road as a place where people of many different backgrounds should feel comfortable; walk or cycle about safely; shop at a variety of small, independent shops or at the now 35-stall market; and importantly, both generate and experience the sense of community that binds together Chatsworth Road’s occupants. With these five criteria, and particularly with the last, the focus on social capital, the CRTRA seeks to differentiate Chatsworth Road’s growth from many areas in London regenerated by markets. It explicitly attempts to avoid the fate of other neighbourhoods, which, originally as diverse as Clapton, morphed into higher-income areas unaffordable to most residents.

An upscale restaurant neighbours an electrical shop on Chatsworth Road. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

Strange as it may seem, the SUB, the group of concerned citizens who put forth a plan for Bucharest’s Uranus neighbourhood, and the Chatsworth Road Neighbourhood Forum have many similarities. They were both formed by people actively interested in shaping their surroundings, in replacing the scars of earlier times with sutures drawing their neighbours and neighbourhoods together. They consist of an assortment of participants, and they represent diverse neighbourhoods in socioeconomic and ethnic terms. In soliciting diverse participation in their plan-making processes, they also seek to preserve the distinct characters of their neighbourhoods, which act as two of few examples of peacefully co-existing, although seemingly disparate, communities in their respective cities. Finally, both groups emphasize the importance of environmental sustainability and accessibility in their plans: though they seek economic development, they want responsible growth beneficial to all inhabitants.

The Chatsworth Road Neighourhood Forum area, with dots representing the distribution of founding members in the neighbourhood. (Image (c) CRTRA website)

Where the groups differ is not in their goals or really even in their composition. Rather, it is their context that sets them apart. While the SUB faces many challenges regarding the approval of its plans, not the least of which is the hard-to-gain support of the city government, the London Borough of Hackney has just approved the Chatsworth Road Neighbourhood Forum’s legal status, and their projects (at this point, at least) seem to be going full steam ahead. The shape of London’s community spaces reflecting local wishes thus continues to evolve. And beyond the passive activity of everyday consumption or the representative activity of casting votes for elected officials, Londoners utilizing the Localism Act’s provisions could begin to play potentially more active roles in the city’s development, changing parts of London’s structure to reflect the needs and wants of its citizens. Bucurestis, by contrast, face continued opposition – explicit as well as implicit – to their desire for participatory planning. The footprint of the city, the state of the streets, the triumph of the car so often seem to reflect more the government’s will than the public’s input.

A screenshot shows the Chatsworth Road Neighbourhood Forum’s website and objectives. (Image (c) CRTRA website)

The comparison between Bucharest’s Uranus neighbourhood (likely to remain stagnant) and the Chatsworth Road site (more likely to grow in a sustainable, socially conscious way) shows the potentially detrimental effects of excluding the community from determining the form of the city. If input is disallowed or disavowed, the city can become a patchwork quilt of political and economic, but not necessarily public, interests. But while there is much at stake with excluding the community from determining the form of the city, there is also much at stake with empowering almost anyone to do so. In both scenarios, there is inevitably someone left out of the process, some interests that are not adhered to in the current generation. Having levels of responsible, people-oriented planning authorities (local, regional, and national governments) could rectify this somewhat by actively soliciting greater participation through many of the channels exercised by groups, such as the SUB or CRTRA, as well as by sifting through those interests to find commonalities and points of convergence. With some coordination of involvement from a wider array of people and of street, neighbourhood, and city goals, planning may begin to reflect the interests of the many, not the few.

The evident disrepair of Bucharest’s buildings, as well as the litter on the streets, are just two by-products of the lack of engagement in the city’s planning process. (Photo (c) Julia Thayne)

But this assumes that those levels of planning authorities exist and that greater participation, unchecked, will not lead to ‘too many cooks in the kitchen’ – with many conflicting visions of how a city should look and function, with collective interests, now expressed at the street level (and diverging on issues of how diversity is best served through planning, for example in relation to appropriate levels of encouragement CRTRA might give to more affordable chains versus independent, upmarket shops as part of the local trading ecosystem), contrasting with collective goals, expressed city-wide.

This new scenario could also lead the city to become a patchwork quilt of public, but not necessarily political and economic, interests, and the result might be just as detrimental as if citizen input was disallowed from the planning process altogether. In addition, questions of planning become exponentially more complicated upon considering not just the current situation, but potential future will. Finding a balance between extremes, between exclusion and participation, between planning for the present and for the future, is an exceptionally complex and difficult process. As citizens, empowered by their own initiative or by the government, increasingly gain control over the space of the city, it calls for close scrutiny these conflicting interests – safeguarding an understanding that who is involved in city-making sometimes has irrevocable results on the urban fabric.

Both personally and professionally, Julia Thayne is interested in utilizing the power of cities to deliver positive economic, environmental, and social change. In pursuit of this goal, she completed her master’s degree in City Design at the London School of Economics & Political Science (LSE). At LSE she co-led an urban design project promoting cycling in London’s most deprived neighbourhoods; co-managed the Sustainable Futures Group, which evaluates and funds student-proposed sustainability projects on LSE’s campus; and just submitted her dissertation on re-using vacant school spaces in the United States. Julia is now a researcher at The Crystal in London, a sustainable cities initiative by Siemens AG. In addition, she writes for Urbanista.org, and has volunteered for and contributed to several conferences on urban issues, including the 2013 Velo-City Conference (on which she reported for Urbanista.org this summer). Prior to LSE, she worked in economic consulting, urban development, and international aid, notably spending three years with Ernst & Young LLP’s Quantitative Economics and Statistics Group (QUEST). At QUEST Julia co-authored several articles and publications on fiscal policy, as well as served as the youngest manager in a new, multi-million dollar service line, which she helped to launch.