3

Issue 3

3

Issue 3

Experiencing a performative audio walk at Arendalsuka, Norway, based on your choice of urban future, part of OAT's events testing ideas and formats, 2018, ahead of the 2019 Triennale. © Arendalsuka/Mona Hauglid.

Dugnad Days at the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2019

Today’s stern realities – social, economic, ecological and cultural – demand incisive responses and action, beyond words and good intentions. The Dugnad Days project matches well the theme of the Oslo Architecture Triennale (OAT) 2019, Enough: The Architecture of Degrowth, announced on 22 May. Through a promising sounding programme of exhibitions, performances and debates, this challenging festival incubates dozens of creative responses by local international architects and practitioners. One of them is Dugnad Days, a participatory design project staged in Slettaløkka, a suburb of Oslo, which were put on display along with all the others in The Library, OAT’s exhibition at the National Museum, Oslo, from 26 Sept 2019.

How should architecture respond to a climate emergency and social division? What kind of architecture will we create when buildings are no longer instruments of financial accumulation? What will our environment look like when it is human and ecological flourishing that matter most?’.

These burning questions are on many people’s minds because they need action and far more attention. They drive the theme of the Oslo Architecture Triennale (OAT) 2019 – entitled ‘Enough: the Architecture of Degrowth’ – which took place in Oslo from 26 September-24 November. Through their Triennale programme of exhibitions, sound installations, theatre, performance, roundtables and workshops, the OAT 2019 curatorial team, British architect and writer Maria Smith; Canadian architect and educator Matthew Dalziel; British critic Phineas Harper; and Norwegian urban researcher and artist Cecilie Sachs Olsen, is challenging the supremacy of economic growth as the basis of contemporary societies and investigating alternatives.

The OAT 2019 curatorial team (l-r): Phineas Harper, Matthew Dalziel, Cecilie Sachs Olsen and Maria Smith. © OAT.

The event aims to uphold OAT’s commitment to engaging and inspiring debate about the future roles of architecture and urbanism between professionals, business communities, decision makers and the public across borders, social layers, sectors and professions, locally, across the Nordic regionally and internationally. In 2018 OAT staged a series of events testing ideas and formats, 2018, ahead of the 2019 Triennale. Together with the art collective zURBS OAT invited participants to go on a performative audio walk at Arendalsuka, the biggest political gathering in the country held annually in mid-August in Arendal, a town on Norway’s southeastern coast since 2012, billed by Visit Norway as ‘where politics meets the man in the street’. People chose to play on their headphones one of three different urban future channels based on degrowth, unlimited economic growth or authoritarian growth as they sashayed through the streets.

Overgrowth – one of the OAT 2019 events in the lead up to the festival opening in early 2019. Phineas Harper and Nikolaus Hirsch along with special guests Ingerid Helsing Almaas, Helena Mattsson, Edgar Pieterse and Marianne Skjulhaug in a series of presentations and conversations around the challenge of growth-based cities and bold alternatives for the architecture of a new economy. © OAT/Istvan Viraq.

OAT’s major exhibition is The Library, staged at the National Museum, a project celebrating the value of sharing, de-commodification, and democratisation of goods and ideas at the heart of a degrowth community. A ‘library of futures’ of over 65 exhibits, it includes drawings, models, materials, artefacts and devices by local and international practitioners presented in four sections, the subjective, the objective, the systemic and the collective.

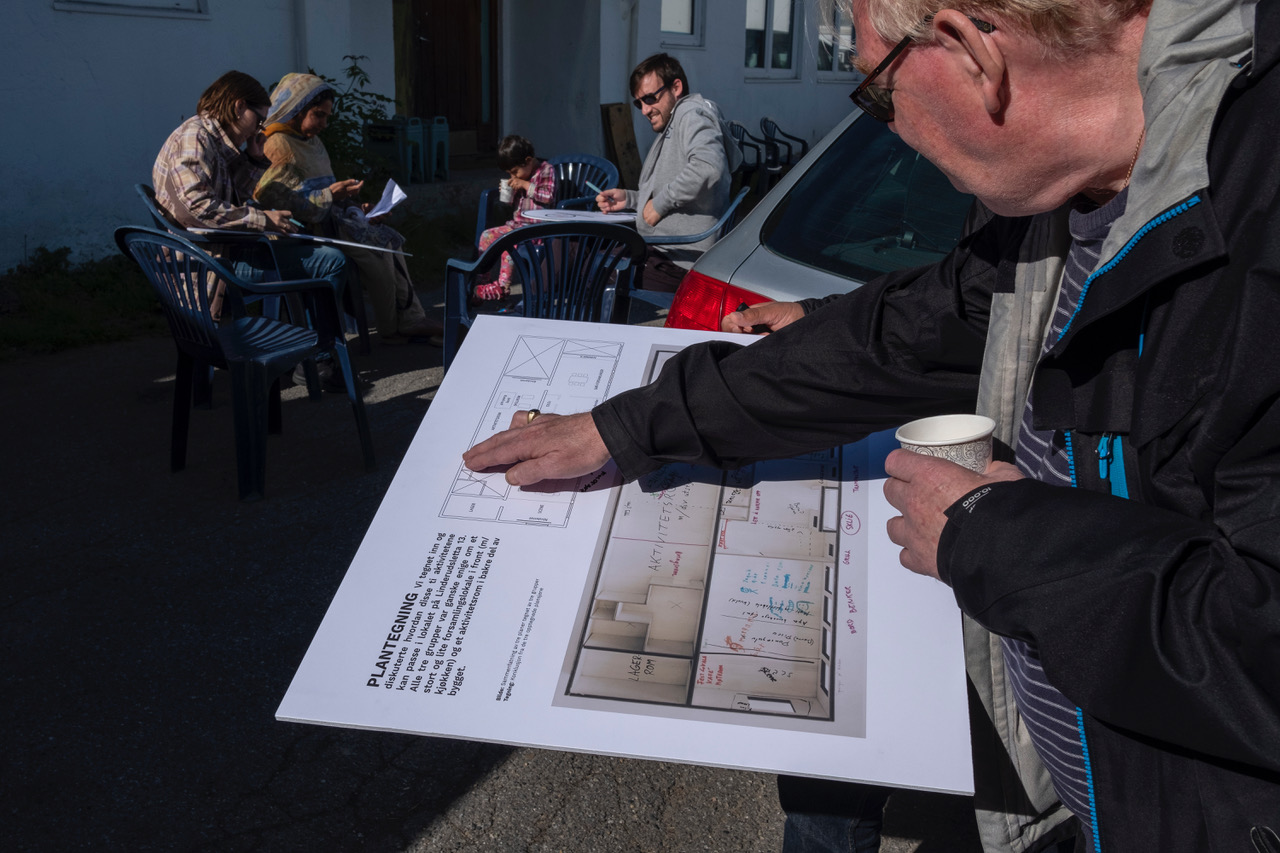

Dugnad Days community workshop at Sletteløkka, Oslo, May 2019, choosing priority activities for the ‘grendehus’, with suggestions added to giant keys.

One of the exhibits, Dugnad Days, shows how a series of local community workshops which began in April can, through participatory placemaking, advance a collective, bespoke process of building resilience and the social sustainability of Sletteløkka, a suburb of Oslo. Dugnad Days is coopting the longstanding Norwegian dugnad tradition of co-production and co-creation with citizens – practices fostering human and environmental wellbeing. With support from Bydel Bjerke, the local borough council, one of the main funding partners of Dugnad Days and through a process of dugnad-inspired workshops with members of the local community to create a versatile ‘grendehus’ – a community centre on a ten year lease – from a disused kindergarten building – the aim is to facilitate a process of direct democracy at Sletteløkka impacting community wellbeing and self-determination. Each of the six dugnads spread over six months culminates with food, drink and music masterminded by participants, as a sociable and relaxing complement to the painstaking collective work of reprogramming, designing and renovating the building, incrementally forging their own asset and legacy.

Alexander Eriksson Furunes, a Norwegian architect and participatory design specialist; Lucy Bullivant, a British place strategist, curator and author – and founder and creative director of Urbanista.org; Mattias Josefsson, architect and teacher at AHO (Oslo School of Architecture) & BAS (Bergen Architecture School) and Maria Årthun, a recent architecture graduate of AHO and co-founder of Makers’ Hub, are the team responsible for Dugnad Days, with architect Sudarshan Khadka, artist and graphic designer Gabriela Forjaz and Maria Cau Levy, architect and graphic designer (members of the Brazilian art/architecture collective Goma Oficina, São Paulo), sound artist Caroline Jinde and performance artist Tuoman Laitinen.

Dugnad Days community workshop at Sletteløkka, Oslo, May 2019, choosing priority activities for the ‘grendehus’, with suggestions added to giant keys.

The project started in April with Furunes, Josefsson and Årthun running a number of idedugnad (ideas) workshops in Sletteløkka. At these, community members have been brainstorming and summarising the activities they want to prioritise for their ‘grendehus’ (community centre). Their discussion revolved around how these activities could be managed, and what each one needed in the way of elements, resources and plans. Then responsibility for each one was assigned to a key person or people, from within the group. A reporter from the local newspaper in Sletteløkka joined the second workshop and gave the project a good write up.

With two workshops under their belt, the local residents taking part used the opportunity to set up their own Velforenging (residents’ association) of Sletteløkka. The community members first had the idea of creating a community ‘grendehus’ in their neighbourhood 8 years ago, and identified a building formerly used as a kindergarten and a grocery store, dating from the late 1950s, the same era as the rest of the area. Bydel Bjerke has always been very enthusiastic about community placemaking here, and is renting the south facing spaces, 250m2 in size, for ten years, and everyone has the ambition to build something of value for the community there in perpetuity. So the Dugnad Days project serves as a ‘warm up’ for that longer term, more permanent solution.

Empowered by their formal status and with clarity on everything they want to achieve to make the community centre happen, they then move on to byggedugnad (construction) workshops to bring the resulting overall spatial and artefact designs into being. Bullivant, who co-curated the Dugnad Days project, is creating a storytelling thread about the project on Urbanista.org. On show to the public in OAT’s Library exhibition from 26 September for the Dugnad Days project are visuals documenting what everyone did at the workshops and, to help visitors implement their own dugnad for a local project of theirs, as part of an illustrated booklet about dugnad-inspired participatory processes. A short documentary film has been made by Aurora Brekke about Sletteløkka, the lives of community members and the role of the new community centre, also screened in the community section of The Library exhibition.

Dugnad Days fits in well with degrowth, the theme of Enough. Degrowth is not a term you hear or read about in the media, but it is a valuable concept, signifying a necessary shift in perspective and priorities for living away from the world’s GDP growth paradigm. As we know, GDP growth is driven by logics of progress and development, the privatisation and the austerity policies of the institutions of the free market and the knock-on damage to social bonds.

Dugnad Days community workshop at Sletteløkka, Oslo, May 2019, choosing priority activities for the ‘grendehus’, with suggestions added to giant keys.

The second Dugnad Days community workshop was featured in Sletteløkka’s local newspaper, May 2019. The local residents took this opportunity to establish the first Velforening (residents’ association) of Sletteløkka.

Sociologist Marco Deriu defines degrowth as the refoundation of ‘a democratic freedom and of new civil rights’ which ‘should be affirmed against a more and more pervasive economic tyranny’. To meet ‘ecological, social and anthropological challenges’ this course of action – while acknowledging the limits of resources – entails ‘the invention of new deliberative arenas’, he wrote in his article ‘Democracies with a future: degrowth and the democratic tradition’ (Elsevier, 2012).

How can the idea of degrowth be genuinely instrumental in opening up alternative architectural practices? The OAT 2019 curatorial team sees many different ways to overcome what they call ‘deeply ingrained perceptions of tomorrow’s possibilities’. They hope through this year’s OAT event to foster a ‘architecture of alternatives’ degrowth movement, based on ‘new measures of human and environmental wellbeing’ and a genuinely equitable sharing of resources.

Dugnad Days is one of a host of fascinating sounding projects that make up OAT 2019 – which has already tested the water with events anticipating its curatorial programme over the last year. It epitomizes how through focussing their own work and values in their local community, drawing on a rich tradition reinvented for today’s and tomorrow’s challenges, citizens can foster a degrowth approach to sustainable futures. Characterised by cultural richness and social justice, it is one they can and will continue to build together on their own terms. The stakes are far too high for that not to happen.